Human-Wildlife Conflict: Polar Bears (Ursus maritimus) and Indigenous Communities

Posted: May 17, 2019 Filed under: ERES525, Module Critique Assignment | Tags: arctic, climate change, Conflict Resolution, culture, environment, Government, human-wildlife conflict, indigenous, polar bear, value Leave a commentBy Alice Hales

Abstract

Due to human activity, the temperature of the atmosphere is on the rise and global climate change is taking its toll (7). Polar bears (Ursus maritimus) are an arctic species reliant on steadily declining sea ice (7). The range shifts in polar bears due to food scarcity has pushed them to encroach on urban areas. Due to the dangerous nature of the bears to humans and properties, human-wildlife conflict arises (19). The endangered status of the bears means that both the safety of indigenous communities and the bears conservation are both top priorities (17). Several short-term solutions, such as waste management, proper food storage and education on bear encounters can help to reduce attacks (5). Though co-management between indigenous Inuit communities and conservation biologists is the only way to greatly reduce conflict in the long-term (6). Places such as Nunavut in Canada, have already lead the way with policy changes and local involvement to maintain the dignity of the people and effective management of the animals (8).

Introduction

Defined by the World Wildlife Fund (WWE), human-wildlife conflict is the interaction between humans and animals that negatively impacts the people, animal, resources or habitat involved (19). The frequency and severity of conflict between humanity and animals will likely increase exponentially as climate change progresses (7). The human population is growing larger, and the changing climate is forcing species to migrate away from unfavourable conditions (7).

Polar bear populations (Ursus maritimus) are in the direct firing line of climate change. The temperature increase of the Arctic is causing a 14% decrease in the sea ice habitat annually of the endangered bears (2). Habitat loss has driven the steady decline of bear populations, and those that survive suffer loss of condition, malnourishment, stunted growth and reduced reproduction (2, 13). The additional cost of forced range shifts in polar bears is encroachment on urban areas (17). Local indigenous communities in the Canadian territory claim a dramatic increase in the number of human-bear interactions (17). Polar bears are dangerous predators and pose a great threat to the communities they are now invading (15). Property damage and trash spreading can be extensive, causing financial losses and cleanup after a bear interaction (16). WWF is working with the effected communities to improve food and waste management, conduct community patrols, improve awareness, use of technology and conduct research to combat this conflict issue (18). These solutions are needed, and already proving to be effective; ensuring it does not become a trade-off between human safety and polar bear conservation (15).

Urban Encroachment of Polar Bears

Polar bear prey, comprised largely of seal species, rely on algae that grows on sea ice (15). The reduction of ice induces food shortages for polar bears, forcing them to find alternative nourishment and migrate northward (15). Large portions of polar bear habitat are predicted to become seasonally ice-free in the coming years, including the southern Beaufort Sea (11). Trash-picking, scavenging and defensive behaviour towards humans is becoming a learned behaviour; transmitted from mother to offspring (15).

Bears have been known to attack, injure or kill humans when interactions occur, potentially even seeing us as prey (3). They can cause extensive property damage of up to thousands, inducing financial hardships in targeted areas (3, 16). Replacing food preservation and transport equipment, or hiring bear monitors are all expensive realities (10). Tourism in arctic areas is becoming more popular, having a positive influence on the economy but increasing risk of interaction (16). Despite the threat they pose, polar bears are endangered and a high priority in conservation (9). Due to conflict with humans, 618 bears were killed in self defence in areas of Canada between 1970 and 2000 (9).

Polar bears have been protected under the ‘International Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears and Their Habitat’ since 1973 (6). Though there is debate that the protection of the bears has not kept up with their rapidly changing situation (6). Inuit communities, such as those in Nunavut and Manitoba, are in close proximity to the bears (6, 16). The photo below (Figure 1) shows a bear searching for food in a dumping area in the small town of Arviat in Nunavut (1).

Figure 1. Polar bear searching for food in rubbish heap. Nunavut, Canada. (1)

Management of the Issue

Attracted by the smell of meat, polar bears will seek poorly kept meat or abandoned carcasses (18). Bear-proofing bins (shown in Figure 2) can reduce triggering the animals. Since the installation of these steel disposal structures (Figure 2), the community of Arivat had a decrease in sightings and approximately seven less bears are killed every year (18). Thermal/infrared fencing around dumps is a new cost effective way of monitoring behaviour (18). This technology will send a text message to the person patrolling the area, alerting them of a bear’s presence (18).

Figure 2. Steel food storage bins to deter bears from enticing waste. This has seen a decrease in bear sightings and shootings since installation. Arviat in Nunavut, Canada (18).

A limitation to many mitigation options is cost. WWF has funded training and steady income for those who work to deter bears and ensure safe communities (18). Bear patrol and work safety workshops combine knowledge from many different places, including Russia, to share the best ways of reducing danger (18). Providing education to those who work in compromising jobs (such as mining or tourism) has increased confidence and reduced fatal accidents when encountering these animals (18).

Long term solutions to human-wildlife conflict in this sense will come from sufficient indigenous involvement and co-management (6, 8). Policies, on the protection of bears and communities alike, will combine traditional values and customs with realistic conservation goals. Change from the top-down takes time and evidence of a problem; yet the solutions above will mitigate the negative impact of the bears while more permanent adaptive capacity is improved.

Local Community Involvement

When conserving a species, it is essential to understand the values and traditions of locals. Without policies that protect the human populations as well, harmful interactions may be elevated and illegal action may be taken (8). The local communities and organisations in Nunavut are acting to resolve human-wildlife conflict together (8). The hunting of polar bears is sacred for Inuit tribes to welcome their children into adulthood; and the number of polar bears in the area was raising safety concerns in the wider community (8). Traditional knowledge and practices should be valued in this situation.

The Government of Nunavut saw the potential for escalated conflict if this rite of passage was taken away from the tribes. Inuit communities hold the bears in high respect and support wildlife management. Co-management of the bears between government, wildlife trusts and Inuit communities is now being put in place (8). The ‘Inuvialuit Land Claim’ has overcome the limitations of conflict allowing indigenous people rights to the land (14). Special permission for traditional hunting on a limited number of the population was retained, biologists work to protect mothers and cubs while few males can be legally harvested (14). Excluding local knowledge and practices in an area, or with a species, escalates conflict and causes tension. Policies combining modern science and indigenous views encourages problem solving and effective management (8). his collaborative approach has helped to mitigate the ill effects of polar bear interactions while allowing traditional customs to continue. A positive outcome for both conservation and the wider community.

Conclusion

Due to a continuous rise in global warming, sea ice has been rapidly disappearing from the arctic (2). Polar bears are predators and threaten the lives and property of humans, inducing human-wildlife conflict. To protect their families and assets, locals are sometimes forced to act against the bears.

Although the bears are under protection, indigenous communities fall victim of lack of policy change to accommodate their values and safety (8). Communities and government in Nunavut, Canada have worked to create a solution. Co-management of indigenous knowledge and practices combined with modern science and biology reduces conflict (8). By acknowledging that Inuit communities have rights to the land and traditional methods, different groups can work together on goals to conserve the bears (6). Education in the workforce and on behaviour, food storage, community patrols, waste management and technology are effective strategies to reduce their chance of negative encounters (12). These mitigation strategies have proven to reduce the number of attacks, accidents, bear sightings and lethal defence (18). Eradicating all conflict between humans and polar bears is unrealistic, though strategies and governing to greatly reduce negative effects are hopeful in the foreseeable future.

References

- BBC News & Rollin, L. (2015). The polar bears are coming to town. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-34490185

- Bromaghin, J. F., McDonald, T. L., Stirling, I. , Derocher, A. E., Richardson, E. S., Regehr, E. V., Douglas, D. C., Durner, G. M., Atwood, T. & Amstrup, S. C. (2015), Polar bear population dynamics in the southern Beaufort Sea during a period of sea ice decline. Ecological Applications, 25, 634-65.

- Can, Ö. E., D’Cruze, N., Garshelis, D. L., Beecham, J. & Macdonald, D. W. (2014). Resolving Human‐Bear Conflict: A Global Survey of Countries, Experts, and Key Factors. Conservation Letters, 7, 501-513.

- Clark, D. A., Van Beest, F. & Brook, R. (2013). Polar Bear-human conflicts: state of knowledge and research needs. Canadian Wildlife Biology and Management, 1, 21-29.

- Clark, D., Clark, S., Dowsley, M., Foote, L., Jung, T., & Lemelin, R. (2010). It’s Not Just about Bears: A Problem-Solving Workshop on Aboriginal Peoples, Polar Bears, and Human Dignity.Arctic, 63(1), 124-127.

- Clark, D., Lee, D., Freeman, M., & Clark, S. (2008). Polar Bear Conservation in Canada: Defining the Policy Problems.Arctic,61(4), 347-360.

- Collaborative Partnership on Sustainable Wildlife Management (CPW). (2015). Sustainable wildlife management and human-wildlife conflict. Retrieved from: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4893e.pdf

- Dowsley, M., & Wenzel, G. (2008). “The Time of the Most Polar Bears”: A Co-Management Conflict in Nunavut.Arctic, 61(2), 177-189.

- Dyck, M.G. (2006). Characteristics of polar bears killed in defense of life and property in Nunavut, Canada, 1970–2000. Ursus,17(1), 52-62.

- IUCN/Polar Bear Specialist Group. (2001). IUCN/Polar Bear Specialist Group 13th meeting. Retrieved from: http://pbsg.npolar.no/en/meetings/stories/13th_meeting.html

- Lillie, K. M., Gese, E. M., Atwood, T. C., & Sonsthagen, S. A. (2018). Development of on-shore behavior among polar bears (Ursus maritimus) in the southern Beaufort Sea: inherited or learned?.Ecology and evolution, 8(16), 7790–7799.

- Polar Bears International (PBI). (2017). News Release: Polar Bear Attacks, Causes, and Prevention. Retrieved from: https://polarbearsinternational.org/news/article-research/news-release-polar-bear-attacks-causes-and-prevention/

- 4 Rode, K. D., Amstrup, S. C. & Regehr, E. V. (2010), Reduced body size and cub recruitment in polar bears associated with sea ice decline. Ecological Applications, 20, 768-782.

- Sillero-Zubiri, C., & K. Laurenson. (2001). Interactions between carnivores and local communities: Conflict or co-existence?. Proceedings of a Carnivore Conservation Symposia, 282-312.

- Thiemann, G. W., Iverson, S. J. & Stirling, I. (2008). Polar Bear Diets and Arctic Marine Food Webs: Insights from Fatty Acid Analysis. Ecological Monographs, 78, 591-613.

- Towns, L., Derocher, A.E., Stirling, I., Lunn, N.J. & Hedman, D. (2009). Spatial and temporal patterns of problem polar bears in Churchill, Manitoba. Polar Biol., 32, 1529‐

- Wilder, J. M., Vongraven, D., Atwood, T. , Hansen, B. , Jessen, A. , Kochnev, A. , York, G. , Vallender, R. , Hedman, D. & Gibbons, M. (2017), Polar bear attacks on humans: Implications of a changing climate. Soc. Bull., 41, 537-547.

- World Wildlife Fund (WWF). (2015). Conflict. Retrieved from: https://arcticwwf.org/species/polar-bear/conflict/

- World Wildlife Fund (WWF). (2019) Human-Wildlife Conflict. Retrieved from: https://wwf.panda.org/our_work/wildlife/problems/human_animal_conflict/

Interdisciplinary Thinking and the Bionic Leaf: Ecological Restoration’s Newest Superheroes

Posted: May 2, 2018 Filed under: ERES525 | Tags: atmosphere, biodiversity, bionic leaf, carbon dioxide, climate change, conservation, ecological restoration, fertiliser Leave a commentBy Leah Churchward

New tools and interdisciplinary approaches are required for conservation in today’s climate, in particular for ecological restoration. In our rapidly changing world, it is important to be able to recognize these new tools and approaches and support them so that they can be funded, developed, and implemented on a large scale. In the case of ecological restoration, this might mean taking a step back from nature reserves and other traditional management methods and focusing on a tool from another discipline. Ecological restoration has the potential to be much more than returning plants and animals to where we found them. The development of the bionic leaf is one example of a newer technology that was created from an interdisciplinary background of biology and chemistry. It has the potential to serve a major role in modern ecological restoration and to reduce the need for ecological restoration as a whole.

(Source: Harvard University)

The bionic leaf was developed by Pamela Silver, a professor of biochemistry at Harvard Medical School, and Daniel Nocera, a professor of energy (also at Harvard University). It is able to split water molecules from natural solar energy and to produce liquid fuels from hydrogen eating bacteria (1). The bacterium Ralstonia eutropha, in combination with the catalysts of the artificial leaf, is used as a hybrid inorganic-biological system. (2) This combination is able to drive an artificial photosynthetic process for carbon fixation into biomass and liquid fuels (2). This artificial photosynthesis transpires through the solar electricity from the photovoltaic panel which is enough to power the chemical process that splits water into hydrogen and oxygen. (7) The pre-starved microbes then feed on the hydrogen and convert CO2 in the air into alcohol fuels. (7)

Initially, the bionic leaf was created to make renewable energy accessible at a local scale for developing communities that are without an electricity grid (3). This new technology also has the potential to intake carbon dioxide from the atmosphere (mentioned above), reduce CO2 emissions and pollution, and provide cleaner fertiliser. In the current era of the Anthropocene, human practices and behaviours have had an impact on the entire planet. One of the most significant consequences is the unprecedented influx of CO2 in the atmosphere over the last century. This is taking its toll on ecosystems around the world and the unique flora and fauna that inhabit them. The field of ecological restoration is a result of the efforts to restore ecosystems negatively affected by anthropogenic activities.

(Source: Schroders)

A majority of the world’s population live in cities that are near biodiversity hotspots. There are 24 megacities (cities with 10 million inhabitants or more) located in lesser developed regions, with an additional 10 cities in developing nations projected to become megacities sometime between 2016 and 2030. (4) With over half of the world’s population living in cities, a great deal of power and fuel is required, and currently a majority of the world’s energy consumption is from fossil fuels. These same fossil fuels are responsible for the increased CO2 in the atmosphere. The first opportunity the bionic leaf brings for ecological restoration is by removing CO2 while performing artificial photosynthesis to begin to restore the atmosphere’s composition to pre-industrial times. (2) The second is by bringing clean and accessible fuel to developing communities, eliminating the need to build facilities such as mining operations, and reducing the need for ecological restoration to begin with. (6) This will create a diminishing reliance on fossil fuels and the land, air, and sea pollution that comes with their use. Besides pollution, climate change has affected the timing of reproduction in animals and plants, the migration of animals, the length of the growing season, species distributions and population sizes, and the frequency of disease and pest outbreaks. (5) It is projected to affect all aspects of biodiversity and therefore should be considered in restoration tactics. (5)

(Source: Harvard University)

The bionic leaf also has been transformed into a system that is able to make nitrogen fertiliser. When added to soil, a different engineered microbe can make fertiliser on demand. (6) Unlike most fertilisers used today in the agricultural industry, this one would not be synthesized from polluting resources. (7) Agricultural frontiers, or the outer regions of modern human settlements, are concentrated in diverse tropical habitats that are home to the largest number of species that are exposed to hazardous land management practices like pesticide use. (8) Because of their high biodiversity, these areas contain more sensitive, vulnerable and endemic species, and are areas expected to undergo the highest rate of species losses. (8) A lack of resources and education on proper pesticide usage has led to sharp deviations from agronomical recommendations with the overutilization of hazardous compounds. (8) Bringing the bionic leaf to these regions would mean cleaner fertiliser and the resources and education for proper pesticide usage. This would help mitigate the damage from improper use of hazardous pesticides as well as protect the biodiversity that was harmed by ingesting them.

Ecological restoration in a changing world calls for new tools and interdisciplinary approaches. When the field of conservation biology was officially established in 1985, the problems of global climate change were just beginning to be understood, as well as the effects on animal and plant species. Ecological restoration is an important section of the conservation biology field but the research and management strategies used going into the future should focus on having a more interdisciplinary approach. The bionic leaf is just one tool from collaborative thinking that can help restore biodiversity and habitats as well as clean up our atmosphere to reduce the need for major restoration projects in the future.

References

1. Peter Reuell. 2016. Bionic Leaf Turns Sunlight into Liquid Fuel. The Harvard Gazette. Accessed April 2018. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2016/06/bionic-leaf-turns-sunlight-into-liquid-fuel/

2. C. Liu, B.C. Colón, M. Ziesack, P.A. Silver, D.G. Nocera. Water Splitting-Biosynthetic System with CO2 Reduction Efficiencies Exceeding Photosynthesis. Science. Vol. 352. Issue 6290. 1210-1213. (2016). DOI: 10.1126/science.aaf5039

3. W.J. Sutherland, P. Barnard, S. Broad, M. Clout, B. Connor, I. M. Côté, L. V. Dicks, H. Doran, A. C. Entwistle, E. Fleishman, M. Fox, K. J. Gaston, D. W. Gibbons, Z. Jiang, B. Keim, F. A. Lickorish, P. Markillie, K. A. Monk, J. W. Pearce-Higgins, L. S. Peck, J. Pretty, M. D. Spalding, F. H. Tonneijck, B. C. Wintle, N. Ockendon, A 2017 Horizon Scan of Emerging Issues for Global Conservation and Biological Diversity, Trends in Ecology & Evolution, Vol. 32, Issue 1, Pages 31-40. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.11.005.

4. United Nations. 2016. The World’s Cities in 2016. Available from http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/urbanization/the_worlds_cities_in_2016_data_booklet.pdf. (Accessed April 27, 2018)

5. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change and Biodiversity. Technical Paper V. 2002. http://ipcc.ch/pdf/technical-papers/climate-changes-biodiversity-en.pdf. (Accessed April 27, 2018)

6. Veronika Meduna. 2017. Bionic Leaf Might Power Earth. Stuff, New Zealand. https://www.stuff.co.nz/science/96110864/bionic-leaf-might-power-earth. (Accessed April 18, 2018).

7. David Biello. Bionic Leaf Makes Fuel From Sunlight, Water and Air. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/bionic-leaf-makes-fuel-from-sunlight-water-and-air1/ (Accessed April 26, 2018).

8. L. Schiesari, A. Waichman, T. Brock, C. Adams, B. Grillitsch. Pesticide Use and Biodiversity Conservation in the Amazonian Agricultural Frontier. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. Vol. 368. (2013). DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0378.

Climate Change: Shifting Wildlife Disease Dynamics

Posted: April 29, 2018 Filed under: ERES525 | Tags: amphibians, climate change, disease, temperature Leave a commentBy Linzy Jauch

Emerging infectious disease threatens biodiversity as it causes significant ecologic shifts in response to a changing climate. Climate change provides opportunities for infectious disease to emerge through elevated mean temperatures, extreme temperature variation, and altered global patterns of precipitation 4,8. Environmental change has the potential to alter physiological and ecological traits of disease such as host-pathogen interactions, pathogen resistance and range distribution. Recent discoveries in wildlife diseases such as Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) in amphibians 2 or blue tongue virus (BTV)4 in ruminants is allowing us to understand to the extent in which climate change is altering disease.

Bd infection of the skin causing death through cardiac arrest. Photo: SOLVIN ZANKL/ VISUALS UNLIMITED/ CORBISFI

Today, one-third (32.5%) of the Earth’s amphibians are threatened with extinction6. The pathogenic fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis has been tied to the extinction of 50-80 species worldwide 2 and continues to threaten global amphibian biodiversity. The fungus attacks the moist skin of amphibians and causes degeneration15. Amphibians use their skin in respiration and in balancing essential ions13 within the body. The fungus creates an imbalance in essential ions within the body that result in death through cardiac arrest13. Though rates of infection have been increasing, Bd is not new to species rich environments7, amphibian immune systems were just previously able to fend off infections.

Climate change has altered the disease dynamics of Bd, specifically host-pathogen interactions and pathogen resistance4. Amphibians are ectothermic, relying on external sources to regulate their body temperature and regulate bodily processes such as metabolism and immune responses. Increased climate variability results in temperature fluctuations that subject amphibians to thermal stress. Documented outbreaks of Bd coincide with dramatic changes in temperatures over a short period of time, characteristic of climate change10. Ectothermic species are more susceptible to thermal stress at temperatures in which they are unaccustomed2 due to an inability to quickly acclimate and match their body temperature with the envrionment4. When temperature changes rapidly, there is an acclimation lag in which the amphibian is adjusting bodily functions to coincide with the temperature shift. However, microbes and pathogens have a broader range of temperature tolerances2 and acclimate quickly8. This thermal mismatch creates a window of opportunity for infection that was less frequent before human-caused climate change caused increased regional temperature variation. Monthly and diurnal fluctuations in temperature decreases amphibian resistance to Bd by suppressing immune defenses that are relient on the amphibian’s ectothermic physiology. Together, through a slow acclimating immune response and a suppressed immune system, Bd is becoming an epidemic.

While Bd’s emergence is in response to changes in host-pathogen interactions, other infectious diseases such as blue-tongue virus in ruminants has undergone a different type of shift in response to climate change. The disease is transferred though the bites of cold-sensitive midges and has been responsible for mass mortalities of sheep and cattle in the Mediterranean region14. Higher average temperatures have led to the northward expansion of midges, and thus an expansion of the BTV range4. The expansion provides new opportunities for the infection of new hosts and threatens domestic and wild ruminant biodiversity.

Regions in blue demonstrate areas now suitable for BTV based on current climate data and increased average temperatures allowing range expansion. Original ranges in North Africa and in the Middle East (4). Chart by Samy and Peterson 2016.

Disease dynamics are altering in response to human-caused climate change7 and are contributing to more extinctions than we originally suspected. The link between human-mediated climate change and infectious disease is complicated due to many intertwining factors5 and must be teased apart to understand what can be done to prevent future emerging infectious diseases. Infectious disease is significantly impacting complex ecologic processes. Biodiversity loss, abandoned niches, and new host infections have already resulted as a response to climate change and infectious disease emergence. Future research focused on understanding the extent to which biodiversity loss has been magnified through infectious disease emergence is necessary for developing mitigation methods that may save small and endangered wildlife populations from extinction.

References

[1] Altizer S, Ostfeld RS, Johnson PT, Kutz S, Harvell CD. 2013. Climate Change and Infectious Diseases: From Evidence to a Predictive Framework. Science 341: 514 – 519.

[2] Cohen J. 2016. Climate Change Drives Outbreaks of Emerging Infectious Disease and Phenological Shifts. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of South Florida, Tampa, USA.

[3] Daszak P, Cunningham AA, Hyatt AD. 2001. Anthropogenic environmental change and the emergence of infectious diseases in wildlife. Acta Tropica 78: 103-116.

[4] Gallana M, Ryser-Degiorgis MP, Wahli T, Segner H. 2013. Climate change and infectious diseases of wildlife: Altered interactions between pathogens, vectors and hosts. Current Zoology 59(3): 427-437.

[5] Lafferty KD. 2009. The ecology of climate change and infectious diseases. Ecology 90(4): 888-900.

[6] Lips KR, Brem F, Brenes R, Reeve JD, Alford RA, Voyles J, Carey C, Livo L, Pessier AP, Collins JP. 2006. Emerging infectious disease and the loss of biodiversity in a Neotropical amphibian community. PNAS 103(9): 3165-3170.

[7] Pounds JA, Bustamante MR, Coloma LA, Consuegra JA, Fogden MPL, Foster PN, Marca EL, Masters KL, Merino-Viteri A, Puschendorf R, Ron SR, Sánchez-Azofeifa, Still CJ, Young BE. 2006. Widespread amphibian extinctions from epidemic disease driven by global warming. Nature 439: 161-167.

[8] Raffel TR, Halstead NT, McMahon TA, Davis AK, Rohr JR. 2015. Temperature variability and moisture synergistically interact to exacerbate an epizootic disease. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 282(1801).

[9] Raffel TR, Romansic JM, Halstead NT, McMahon TA, Venesky MD, Rohr JR. 2013. Disease and thermal acclimation in a more variable and unpredictable climate. Nature Climate Change 3: 146-151.

[10] Rohr JR and Raffel TR. 2010. Linking global climate and temperature variability to widespread amphibian declines putatively caused by disease. PNAS 107(18): 8269-8274.

[11] Rohr JR, Raffel TR, Romansic JM, McCallum H, Hudson PJ. 2008. Evaluating the links between climate, disease spread, and amphibian declines. PNAS 105(45):17436-17441.

[12] Rohr JR, Schotthoefer AM, Raffel TR, Carrick HJ, Halstead N, Hoverman JT, Johnson CM, Johnson LB, Lieske C, Piwoni MD, Schoff PK, Beasley VR. 2008. Agrochemicals increase trematode infections in a declining amphibian species. Nature 445(30): 1235 -1239.

[13] Rollins-Smith LA. 2017. Amphibian immunity – stress, disease, and climate change. Developmental and Comparative Immunology 66:111-119.

[14] Samy AM and Peterson AT. 2016. Climate Change Influences on the Global Potential Distribution of Bluetongue Virus. PLoS ONE 11(3).

[15] Vredenburg VT, Knapp RA, Tunstall TS, Briggs CJ. 2010. Dynamics of an emerging disease drive large-scale amphibian population extinctions. PNAS 10(21): 9689-9694.

[16] Yang Xie G, Olson DH, Blaustein AR. 2016. Projecting the Global Distribution of the Emerging Amphibian Fungal Pathogen, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, Based on IPCC Climate Futures. PLoS ONE 11(8).

Novel ecosystems Concept: Synthesis of existing currents of thoughts, and when to consider it.

Posted: May 1, 2017 Filed under: 2017, ERES525 | Tags: climate change, ecosystem management, ecosystem services, exploited species, hybrid ecosystems, invasive species, novel ecosystems 1 CommentBy Jeff Balland

The recent concept of novel ecosystems has aroused many debates. Novel ecosystems can be defined as new systems where new species combinations and functions that have never interacted historically, occur irreversibly and sustainably (Morse et al. 2014), due to anthropogenic activities, species introduction and climate change (Hobbs et al. 2006; Hobbs et al. 2009). The stage between an ecosystem and a novel ecosystem is called “hybrid ecosystem”, and can be defined by a changing system where a return to previous conditions is still possible before it reaches a tipping point (see Hobbs et al. 2013). Almost 12 years after its introduction (see also Chapin & Starfield 2005), two sides are opposed, whether restoration ecologists should integrate the concept of novel ecosystems into practice or not. I attempt to expose and criticize both of them to see what should be retained about this issue.

Embracing the concept

The proponents of this approach argue that it is more relevant to adapt to climate change, and help ecosystems to keep their functions and services when their communities are unbalanced by changing conditions. As most of existing ecosystems are concerned by changes, “novel ecosystems constitute the new normal” (Marris 2010).

As climate change affects species ranges, migrations and invasions (Parmesan 2006) and because non-indigenous species introduction is one of the biggest causes of native communities changes (natives can be excluded by losing competition) (Clavero & Garcia-Berthou 2005), promoting novel ecosystem management is to say tolerating invasive species (Rodriguez 2006). Indeed, invasive species removal has a real cost for governances. For instance, the removal costs to USA more than 22 billion dollars per year for all invasive species (Pimentel et al. 2005). Is Invasive Non-Native Species (INNS) removal compulsory? Many studies showed that sometimes, removing those species could have unexpected negative impacts on native species and ecosystems so that recovery of native species after their removal is not allowed (see Zavaleta et al. 2001; Ewel & Putz 2004): some INNS have even been described as keystone and engineer species (species playing a crucial role in the ecosystem) (Rodriguez 2006; Sousa & Gutiérrez 2009). For example, an invasive tree in Puerto Rico allows some native plants to settle where there were not able before (Lugo 2004). Considering this, exotic species should not be neglected just because they are non-native (Davis et al. 2011).

Figure 1. The Hamunara springs in New Zealand, where the Coastal Redwood is naturalized and provides useful ecosystem services in what can be considered as a a novel ecosystem. Credits: N.Y. Chan

By the way, the new concept of assisted migration (translocation of species threatened by climate change into more suitable locations), emerging as a solution to face environmental changes, will permit the creation of novel ecosystems in the areas where species are voluntary introduced (Minteer & Collins, 2010).

Finally, the novel ecosystems approach may allow improving quality of ecosystem services in exploited ecosystems such as plantation forestry or agriculture. In their study, Smaill et al.(2014) showed that the Coast Redwood Sequoia sempervirens matched all the considerations of New-Zealand foresters and could deliver better ecosystem services than the actual most exploited species (Pinus radiata). By the way, the Coastal Redwood is already naturalized in some part of the country (Figure 1).

Critiques

Yet, many scientists strongly disagree with the novel ecosystems concept. In their critique, Murcia et al.(2014) pointed several oversights of such an approach. First, assuming novel ecosystems are “the new normal” is denying successful stories of restoration and ignoring that many ecosystems are well-preserved. Secondly, it is argued that species responses to climate change are unpredictable on a local or regional scale (the usual restoration scales). Furthermore the thresholds of irreversibility in species combination, namely the tipping points determining whether a hybrid ecosystem may recover to the ancestral one or evolve toward a novel ecosystem, are still difficult if not impossible to identify (Aronson et al. 2014). According to the detractors, such a concept could provide a “license to disturb” for resource exploitation companies, and may reduce the investment in research and restoration projects because they may become unnecessary, as transformation of ecosystems may be accepted. At last, introducing or managing new species combinations, often including INNS, is not worth taking the risk and the precautionary principle should be applied to avoid any aggravation of ecosystems perturbations.

Integration in management

According to Hobbs et al.(2014), novel ecosystem approach in conservation can also be an alternative to classical restoration. In this paper, the authors made a framework on how decisions about ecosystem management should be taken (Figure 2), struggling between different limitations the managers could have in regards of management goals.

Figure 2. Framework for decision-making in ecosystem management, integrating the novel ecosystems concept. From Hobbs et al. (2014)

However, according to the authors, this framework is theoretic and crucially need further implementation. By the way, decision-making processes may be influenced by the degree of sympathy managers have towards novel ecosystems.

Conclusion

The novel ecosystem concept is a new way of looking at the environment. Integrating it in management practices may allow to use what were threats (for example invasive species) as advantages (ecosystem functioning). It may help to preserve species that are jeopardized by climate change though assisted migration, and ecosystem services of exploited lands may be enhanced by selecting species in regards of their ecological functions. In my opinion, the concept is not ignoring successful stories of restoration, nor it will provide “licence to disturb”, because novel ecosystems are not worth studying to replace conservation but to provide alternative management. However, I agree some new approaches such as assisted migration are uncertain because of unpredictable species responses (to climate change, to new community compositions, etc.). Likewise, the difficulty of identifying the tipping points in hybrid ecosystem is an obstacle to management decisions. But it is definitely worth putting energy in further investigations, because of all the knowledge about ecosystem functioning the discovery of these thresholds would bring. The concept crucially needs implementation even if the principle of precaution regarding the risks should be considered. That is why I strongly believe the concept should be embraced only as an ultimate alternative, when neither sufficient protection (reserves, protection status for species, conservation programs…) nor classical restoration can be done. In that way, the novel ecosystem approach will only provide good overcomes and exciting discoveries.

References:

Aronson, J., Murcia, C., Kattan, G.H., Moreno-Mateos, D., Dixon, K., Simberloff, D., 2014. The road to confusion is paved with novel ecosystem labels: a reply to Hobbs et al. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 29, 646–647. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2014.09.011

Murcia, C., Aronson, J., Kattan, G.H., Moreno-Mateos, D., Dixon, K., Simberloff ,D., 2014. A critique of the “novel ecosystem” concept. Trends Ecol Evol 29, 548–553. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2014.07.006

Chapin, F.S., Starfield, A.M., 1997. TIME LAGS AND NOVEL ECOSYSTEMS IN RESPONSE TO TRANSIENT CLIMATIC CHANGE IN ARCTIC ALASKA. Climatic Change 35, 449–461. doi:10.1023/A:1005337705025

Clavero, M., García-Berthou, E., 2005. Invasive species are a leading cause of animal extinctions. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 20, 110. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.01.003

Davis, M.A., Chew, M.K., Hobbs, R.J., Lugo, A.E., Ewel, J.J., Vermeij, G.J., Brown, J.H., Rosenzweig, M.L., Gardener, M.R., Carroll, S.P., Thompson, K., Pickett, S.T.A., Stromberg, J.C., Tredici, P.D., Suding, K.N., Ehrenfeld, J.G., Philip Grime, J., Mascaro, J., Briggs, J.C., 2011. Don’t judge species on their origins. Nature 474, 153–154. doi:10.1038/474153a

Ewel, J.J., Putz, F.E., 2004. A place for alien species in ecosystem restoration. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2, 354–360. doi:10.1890/1540-9295(2004)002[0354:APFASI]2.0.CO;2

Hobbs, R.J., Arico, S., Aronson, J., Baron, J.S., Bridgewater, P., Cramer, V.A., Epstein, P.R., Ewel, J.J., Klink, C.A., Lugo, A.E., Norton, D., Ojima, D., Richardson, D.M., Sanderson, E.W., Valladares, F., Vilà, M., Zamora, R., Zobel, M., 2006. Novel ecosystems: theoretical and management aspects of the new ecological world order. Global Ecology and Biogeography 15, 1–7. doi:10.1111/j.1466-822X.2006.00212.x

Hobbs, R.J., Higgs, E., Hall, C.M., Bridgewater, P., Chapin, F.S., Ellis, E.C., Ewel, J.J., Hallett, L.M., Harris, J., Hulvey, K.B., Jackson, S.T., Kennedy, P.L., Kueffer, C., Lach, L., Lantz, T.C., Lugo, A.E., Mascaro, J., Murphy, S.D., Nelson, C.R., Perring, M.P., Richardson, D.M., Seastedt, T.R., Standish, R.J., Starzomski, B.M., Suding, K.N., Tognetti, P.M., Yakob, L., Yung, L., 2014. Managing the whole landscape: historical, hybrid, and novel ecosystems. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 12, 557–564. doi:10.1890/130300

Hobbs, R.J., Higgs, E., Harris, J.A., 2009. Novel ecosystems: implications for conservation and restoration. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 24, 599–605. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.05.012

Hobbs, R.J., Higgs, E.S., Harris, J.A., 2014. Novel ecosystems: concept or inconvenient reality? A response to Murcia et al. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 29, 645–646. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2014.09.006

Lugo, A.E., 2004. The outcome of alien tree invasions in Puerto Rico. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2, 265–273. doi:10.1890/1540-9295(2004)002[0265:TOOATI]2.0.CO;2

Marris, E., 2006. Ecological and Evolutionary Responses to Recent Climate Change. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 37, 637–669. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110100

Marris, E., 2010. The new normal. Conserv. Mag. 11, 13–17

Morse, N.B., Pellissier, P.A., Cianciola, E.N., Brereton, R.L., Sullivan, M.M., Shonka, N.K., Wheeler, T.B., McDowell, W.H., 2014. Novel ecosystems in the Anthropocene: a revision of the novel ecosystem concept for pragmatic applications. Ecology & Society 19, 85–94. doi:10.5751/ES-06192-190212

Pimentel, D., Zuniga, R., Morrison, D., 2005. Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States. Ecological Economics, Integrating Ecology and Economics in Control BioinvasionsIEECB S.I. 52, 273–288. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.10.002

Smaill, S.J., Bayne, K.M., Coker, G.W.R., Paul, T.S.H., Clinton, P.W., 2014. The Right Tree for the Job? Perceptions of Species Suitability for the Provision of Ecosystem Services. Environmental Management 53, 783–799. doi:10.1007/s00267-014-0239-5

Sousa, R., Gutiérrez, J.L., Aldridge, D.C., 2009. Non-indigenous invasive bivalves as ecosystem engineers. Biol Invasions 11, 2367–2385. doi:10.1007/s10530-009-9422-7

Truitt, A.M., Granek, E.F., Duveneck, M.J., Goldsmith, K.A., Jordan, M.P., Yazzie, K.C., 2015. What is Novel About Novel Ecosystems: Managing Change in an Ever-Changing World. Environmental Management 55, 1217–1226. doi:10.1007/s00267-015-0465-5

Will climate change make our current system of nature reserves redundant?

Posted: May 6, 2016 Filed under: 2016, ERES525, Research Essay, Uncategorized | Tags: assisted migration, climate change, range shift, reservation Leave a commentBy Amanda Healy

Ecological reservation is currently used as a primary technique for preserving species or ecosystems. By disallowing the exploitation of an ecosystem, it is assumed that the area will be protected, and will therefore be able to exist into perpetuity. However, due to the rapidly increasing temperatures caused by anthropogenic climate change, many different species are moving away from their previous ranges into more climatically suitable locations (Chen et al., 2011; Loarie et al., 2009). This essay will look at how that may affect ecological reserves, and what we may need to do to keep up with the ever-changing climate.

Images showing predictions for global climate change in the coming years. From express.co.uk

Climate-change induced range shifts are occurring in a vast number of species (Shoo et al.,2006). One study found that on average, species are moving to higher latitudes and altitudes at rates of 16km and 11m per decade, respectively (Chen et al., 2011). These rates obviously vary, depending on the intensity of climate change in any given area and the ranging ability of the species in question; migratory species are able to shift their ranges quickly, but sedentary species (such as trees) take much longer (Parmesan et al., 1999).

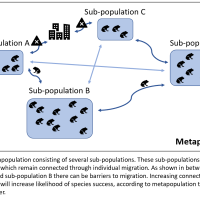

Because of the movement of species out of their original ranges, our current system of protected reserves may become redundant in the future. One estimate states that in 100 years, only 8% of our reserves will still have the same climate as they have today (Loarie et al., 2009). This means that many of the species that we are aiming to protect will no longer be able to live within these reserves. They will either move outside of the reserve’s borders, or even worse, barriers will inhibit their movement and they will go locally extinct.

The protection of these reserved species will likely require assisted colonisation in the future (Lunt et al., 2013). The barriers that inhibit the movement of species, such as habitat fragmentation or the fencing around reservations, mean that these species will need help to move to a habitat that is suitable in the changing climate. The same applies to species that are slow moving or sedentary, as they are unlikely to be able to keep pace with the rate of climate change (Parmesan et al., 1999). This concept goes against traditional ideas of conservation and reservation, as it would often mean introducing a species to a geographical area that they have never occupied previously (Hoegh-Gulberg et al., 2008). Most reservations work to preserve only species that are native to the area. However, in order to save many of these species, it will likely be the best option in the coming years.

For these reasons, it is likely that nature reserves, for the purpose of species or ecosystem preservation, have a limited lifespan. At some point, as temperatures continue to rise and climates continue to move, we will have to reconsider our concepts of reservation ecology. Alternative solutions will need to be considered in order to protect the organisms that these reserves are currently housing.

References

Chen, I. C., Hill, J. K., Ohlemüller, R., Roy, D. B., & Thomas, C. D. (2011). Rapid range shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science, 333(6045), 1024-1026.

Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Hughes, L., McIntyre, S., Lindenmayer, D. B., Parmesan, C., Possingham, H. P., & Thomas, C. D. (2008). Assisted colonization and rapid climate change. Science (Washington), 321(5887), 345-346.

Loarie, S. R., Duffy, P. B., Hamilton, H., Asner, G. P., Field, C. B., & Ackerly, D. D. (2009). The velocity of climate change. Nature, 462(7276), 1052-1055.

Lunt, I. D., Byrne, M., Hellmann, J. J., Mitchell, N. J., Garnett, S. T., Hayward, M. W., … & Zander, K. K. (2013). Using assisted colonisation to conserve biodiversity and restore ecosystem function under climate change.Biological conservation, 157, 172-177.

Parmesan, C., Ryrholm, N., Stefanescu, C., Hill, J. K., Thomas, C. D., Descimon, H., … & Tennent, W. J. (1999). Poleward shifts in geographical ranges of butterfly species associated with regional warming. Nature,399(6736), 579-583.

Shoo, L. P., Williams, S. E., & Hero, J. (2006). Detecting climate change induced range shifts: Where and how should we be looking? Austral Ecology, 31(1), 22-29.

Willis, S. G., Hill, J. K., Thomas, C. D., Roy, D. B., Fox, R., Blakeley, D. S., & Huntley, B. (2009). Assisted colonization in a changing climate: a test‐study using two UK butterflies. Conservation Letters, 2(1), 46-52.

Restoring resilience: Can restoring coasts with ecosystem-based solutions protect social-ecological systems from the impacts of climate change?

Posted: May 2, 2016 Filed under: 2016, ERES525, Research Essay | Tags: #resilience, climate change, coastal hazard, ecosystem-based defence, restoration Leave a commentBy Anni Brumby

Victoria University of Wellington

Background

The destruction of hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005 (Photo 1), extreme flooding on the east coast of Australia in 2007, and last year, my local train station in Porirua completely underwater. Welcome to the stormy and wet world of global climate change.

Many of the threats caused by climate change are especially severe in coastal and low lying areas (Nicholls et al., 2007). This is a major concern, as coasts all over the planet are densely populated. Coastal areas less than 10 metres above sea level cover only 2% of the Earth’s surface, but contain 13% of the world’s urban population (McGranahan, Balk, & Anderson, 2007). Often coasts are highly modified for human purposes, and crucial for economic stability (Martínez et al., 2007).

The observed and predicted coastal hazards include sea level rise and the resulting inundation; erosion and salinization of land (Gornitz, 1991); increased precipitation intensity and run-off; and storm flooding (Nicholls & Lowe, 2004). Climate change will also increase the frequency and intensity of weather extremes, such as hurricanes (Emanuel, 2005; Seabloom, Ruggiero, Hacker, Mull, & Zarnetske, 2013).

The existence of Homo sapiens rely on ecosystem services – “the benefits people obtain from ecosystems” (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005, p. 1), such as food production, raw materials, waste treatment, disturbance and climate regulation, water supply and regulation…The list goes on. Coastal ecosystems contribute 77% of global ecosystem-services value (Martínez et al., 2007), thus any coastal threats affect have major impacts for humans both economically and socially.

It is unlikely that we can stop global warming (Peters et al., 2013), but is there any way to mitigate the risks? Even if we cannot prevent the sea levels from rising or storms raging, maybe we can protect our coastal ecosystems and cities by restoring resilience in social-ecological systems with ecosystem based defence strategies.

Concept of resilience

Resilience was first introduced as an ecological concept by Holling in 1973, the idea mainly referring to dynamic ecosystems that can persist in the face of disturbances. High ecological resilience is closely linked to high biodiversity of ecosystems (e.g. Oliver et al., 2015; Worm et al., 2006). As people are increasingly seen as an integral part of the biophysical world (Egan, Hjerpe & Abrams, 2011), our current understanding of resilience now also includes the human dimension. According to one definition, resilience is the capacity of social-ecological system to sustain a desired set of ecosystem services in the face of disturbance and ongoing evolution and change (Biggs et al., 2012, p. 423).

From human-engineered to ecosystem based defences

For a long time, coastal hazard prevention relied solely on so called “hard solutions”, such as building of sea walls and dykes (Slobbe et al., 2013). Recently there has been a shift towards “softer” approaches. These so called ecosystem-based adaptation or defence strategies aim to conserve or restore naturally resilient coastal ecosystems, such as marshes and mangroves, in order to protect human population from natural hazards (Temmerman et al., 2013). Restoring shores for protection is not a new idea, but it has gained momentum in recent years. Many volunteer groups are focused on restoring coastal ecosystems, such as the Dune Restoration Trust in New Zealand. Globally, the influential Nature Conservancy funds a project called Coastal Resilience, which aims to reduce coastal risks to communities with nature-based solutions (Coastal Resilience, 2016).

Restoring dune vegetation can help reduce erosion, while increasing and maintaining the resilience of coastal zones (Silva, Martínez, Odériz, Mendoza, & Feagin, 2016). Coastal ecosystems, for example forested wetlands and marshes, can play a significant role in reducing the influence of waves (Fig. 1) and floods (Danielsen et al., 2005; Hey & Philippi, 1995; Mitsch & Gosselink, 2000; Seabloom et al., 2013). In southeast India coastal zones with intact mangrove forests and tree shelterbelts were significantly less affected by the catastrophic Boxing Day tsunami in 2004, than the areas where coastal vegetation had been removed (Danielsen et al., 2005). Coastal vegetation can also buffer gradual phenomena such as sea-level rise or tidal changes (Feagin et al., 2009).

Figure 1. A simple figure showing how the wave impact is reduced in healthy coastal habitats due to the buffering effect of different coastal ecosystems, such as marshes. The Nature Conservancy.

One of the benefits of ecosystem-based strategies compared to traditional human-engineered solutions is that they are more cost-efficient. For example, investment of US$1.1 million on mangrove restoration to protect rice fields in coastal Vietnam has been estimated to save US$7.3 million per year in dyke maintenance (Reid & Huq, 2005). In addition, almost 8,000 local families have been able to improve their livelihoods and thus their resilience by harvesting marine products in the replanted mangrove areas (Reid & Huq, 2005).

It has been argued that healthy natural ecosystems are more effective than man-made structures in coastal protection (Costanza, Mitsch, & Day, 2006). For example, the devastating effects of the 2005 flood in New Orleans could partially have been avoided, if the wetlands surrounding the city had not been modified by humans, thus preventing the delta system absorbing changes in water flows (Costanza et al., 2006). The problem is, due to anthropogenic stressors, not many coastal habitats are healthy or in a natural state. This is something that restoration aims to change, but to really make a difference, we have a long road ahead.

Future

Significant mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions is the most crucial action that can be taken to reduce the effects of climate change, but we also need to adapt to the predicted changes by increasing ecosystem management methods sensitive to resilience (Tompkins & Adger, 2004). Traditionally, ecological restoration is based on the idea that we want to return something to its former condition. But ecosystems are not stable or static, never have been, and never will be (Willis & Birks, 2006). The increased risk of climate change induced coastal hazards possesses a major challenge to New Zealand economically, socially and environmentally. We have approximately 18,200 kilometres of shoreline, and one of the highest coast to land area ratios in the world. Most of New Zealand’s towns and cities, including our capital city Wellington, are located by the sea. In order to survive, we need to embrace ecosystem-based solutions and aim to restore for resilience.

References

Biggs, R., Schluter, M., Biggs, D., Bohensky, E. L., BurnSilver, S., Cundill, G., . . . West, P. C. (2012). Toward Principles for Enhancing the Resilience of Ecosystem Services. In A. Gadgil & D. M. Liverman (Eds.), Annual Review of Environment and Resources, Vol 37 (Vol. 37, pp. 421-+). Palo Alto: Annual Reviews

Coastal resilience. (2016). http://coastalresilience.org/ [Accessed on 22 April 2016].

Costanza, R., Mitsch, W. J., & Day, J. W. (2006). A new vision for New Orleans and the Mississippi delta: applying ecological economics and ecological engineering. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 4(9), 465-472. doi:10.1890/1540-9295(2006)4[465:ANVFNO]2.0.CO;2

Danielsen, F., Sørensen, M. K., Olwig, M. F., Selvam, V., Parish, F., Burgess, N. D., . . . Suryadiputra, N. (2005). The Asian Tsunami: A Protective Role for Coastal Vegetation. Science, 310(5748), 643-643. Retrieved from http://science.sciencemag.org/content/310/5748/643.abstract

Egan, D., Hjerpe, E. E., & Abrams, J. (2011). Why people matter in ecological restoration. In Human Dimensions of Ecological Restoration (pp. 1-19). Island Press/Center for Resource Economics

Emanuel, K. (2005). Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years. Nature, 436(7051), 686-688. doi:http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v436/n7051/suppinfo/nature03906_S1.html

Feagin, R. A., Lozada-Bernard, S. M., Ravens, T. M., Möller, I., Yeager, K. M., & Baird, A. H. (2009). Does vegetation prevent wave erosion of salt marsh edges? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(25), 10109-10113.

Gornitz, V. (1991). Global coastal hazards from future sea level rise. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology. Palaeoecology 89(4): 379–398

Hey, D. L., & Philippi, N. S. (1995). Flood Reduction through Wetland Restoration: The Upper Mississippi River Basin as a Case History. Restoration Ecology, 3(1), 4-17. doi:10.1111/j.1526-100X.1995.tb00070.x

Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 4, 1-23. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.helicon.vuw.ac.nz/stable/2096802

Martínez, M. L., Intralawan, A., Vázquez, G., Pérez-Maqueo, O., Sutton, P., & Landgrave, R. (2007). The coasts of our world: Ecological, economic and social importance. Ecological Economics, 63(2–3), 254-272. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.10.022

McGranahan, G., Balk, D., & Anderson, B. (2007). The rising tide: assessing the risks of climate change and human settlements in low elevation coastal zones. Environment and urbanization, 19(1), 17-37.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. (2005). Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Biodiversity Synthesis. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC

Mitsch, W. J., & Gosselink, J. G. (2000). The value of wetlands: importance of scale and landscape setting. Ecological Economics, 35(1), 25-33. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00165-8

Nicholls, R. J., & Lowe, J. A. (2004). Benefits of mitigation of climate change for coastal areas. Global Environmental Change, 14(3), 229-244. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.04.005

Nicholls, R.J., P.P. Wong, V.R. Burkett, J.O. Codignotto, J.E. Hay, R.F. McLean, S. Ragoonaden and C.D. Woodroffe. (2007). Coastal systems and low-lying areas. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 315-356.

Oliver, T. H., Heard, M. S., Isaac, N. J., Roy, D. B., Procter, D., Eigenbrod, F., . . . Petchey, O. L. (2015). Biodiversity and resilience of ecosystem functions. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 30(11), 673-684.

Peters, G. P., Andrew, R. M., Boden, T., Canadell, J. G., Ciais, P., Le Quere, C., . . . Wilson, C. (2013). The challenge to keep global warming below 2 [deg]C. Nature Clim. Change, 3(1), 4-6. doi:http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/v3/n1/abs/nclimate1783.html#supplementary-information

Reid, H., & Huq, S. (2005). Climate change-biodiversity and livelihood impacts. Tropical forests and adaptation to climate change, 57.

Seabloom, E. W., Ruggiero, P., Hacker, S. D., Mull, J., & Zarnetske, P. (2013). Invasive grasses, climate change, and exposure to storm-wave overtopping in coastal dune ecosystems. Global Change Biology, 19(3), 824-832. doi:10.1111/gcb.12078

Silva, R., Martínez, M. L., Odériz, I., Mendoza, E., & Feagin, R. A. (2016). Response of vegetated dune–beach systems to storm conditions. Coastal Engineering, 109, 53-62. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2015.12.007

Slobbe, E., Vriend, H. J., Aarninkhof, S., Lulofs, K., Vries, M., & Dircke, P. (2013). Building with Nature: in search of resilient storm surge protection strategies. Natural Hazards, 66(3), 1461-1480. doi:10.1007/s11069-013-0612-3

Temmerman, S., Meire, P., Bouma, T. J., Herman, P. M. J., Ysebaert, T., & De Vriend, H. J. (2013). Ecosystem-based coastal defence in the face of global change. Nature, 504(7478), 79-83. doi:10.1038/nature12859

Tompkins, E. L., & Adger, W. N. (2004). Does Adaptive Management of Natural Resources Enhance Resilience to Climate Change? Ecology and Society, 9(2). Retrieved from http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss2/art10/

Willis, K. J., & Birks, H. J. B. (2006). What is natural? The need for a long-term perspective in biodiversity conservation. Science, 314(5803), 1261-1265.

Worm, B., Barbier, E.B., Beaumont, N., Duffy, J.E., Folke, C., Halpern, B.S., Jackson, J.B., Lotze, H.K., Micheli, F., Palumbi, S.R. and Sala, E., (2006). Impacts of biodiversity loss on ocean ecosystem services. Science, 314(5800), pp.787-790.