Human implications of Conservation Triage

Posted: May 17, 2019 Filed under: 2019, ERES525, Module Critique Assignment | Tags: biodiversity, conservation management, conservation triage, culture, Human Values, prioritisation Leave a commentBy Matthew Howse (300336880)

Abstract:

Triage is a method of prioritisation where resources are preferentially given to those who have to highest chance and lowest cost of success. This can be applied to conservation where managers aim to protect as much biodiversity as they can often with limited funding. Despite its potential, conservation triage is a controversial concept. It is often argued that it doesn’t take societal and cultural values into consideration. In this discussion, 3 examples of where triage could be applied were considered. Human-related impacts of conservation triage include 1) loss of culturally important species and compensation costs, 2) Abuse of the concept leading to unnecessary extinctions, and 3) potential loss of public engagement due to the extinction of flagship species. Hopefully, the discussion brought on by the consideration of human dimensions in conservation can lead to more effective solutions in the future.

What is Conservation Triage?

Conservation managers must have strategies to achieve their conservation goals using the resources given to them. Conservation triage is a strategy of prioritisation whereby, like medical triage, resources are preferentially given to those who have to the highest chance of success. This strategy is implemented when resources are limited and there are many who require them (Kennedy, Aghababian, Gans & Lewis, 1996).

Conservation biology has been labeled a crisis discipline, whereby conservation managers must often make important decisions quickly and often without knowing all the information (Soule, 1985). Often funding is limited, and the list of species threatened is a fast-growing one. Conservation triage has been suggested as a way for conservation biologists to maximise success with the limited resources they have (Bottril et al., 2008).

Conservation triage may be seen as the key to all conservation issue but as you will see there are hidden flaws. Often this approach fails to consider the human aspects, specifically how our cultural and societal values influence our decisions around conservation. I will discuss these here.

Caribou

In Canada, conservation triage has been suggested as a tool to manage woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) populations. Populations of woodland caribou are declining with some populations going extinct despite current conservation efforts. At current trends, 9 of 12 herds monitored will decline to less than ten individuals in 30-40 years (Schneider, Hauer, Adamowicz & Boutin, 2010). The triage approach has been suggested to save the caribou by focussing on protecting the herds that have the highest chance of success at the expense of the more endangered herds (Schneider, Hauer, Adamowicz & Boutin, 2010; Hebblewhite, 2017). It is believed that this will make better use of the resources available to conservation managers. In this way, the species can be protected more effectively and their population decline may then be halted.

Woodland caribou, Rangifer tarandus caribou (Forrest, 2007).

In this example, no species are lost but potentially important populations are. While the species as a whole may survive, the loss of populations can have unforeseen impacts. The indigenous people of Canada have the right to hunt these species have entrusted the Canadian government to manage the caribou effectively (Schneider, Hauer, Adamowicz & Boutin, 2010; Hebblewhite, 2017). If Caribou populations are left to go extinct the First Nations people will no longer be able to hunt them, losing a vital part of their culture. First Nations people have the right to sue the Canadian government and demand compensation (Hebblewhite, 2017). This adds another cost for conservation managers to consider when implementing conservation triage that is not immediately obvious.

Mud Turtles

The Sonora mud turtle (Kinosternon sonoriense) is a species that is relatively common but does face threats to its survival with population decline common throughout its range in Arizona and New Mexico, USA. It has been suggested as a species that would greatly benefit from a triage approach to conservation (Stone, Congdan & Smith, 2014). It is not a well-known species and its plight is often overshadowed by other critical or well-known species. Despite the often cheaper cost of securing a species population early, these low priority species receive little attention or funding (Stone, Congdan & Smith, 2014). A Triage approach to conservation would ensure that this species received a higher priority but at the cost of pulling funding and focus away from the more critically endangered species. Theoretically, this would increase the benefit to biodiversity as more species would be saved. The cost, however, would likely be the extinction of other species.

Sonora mud turtle, Kinosternon sonoriense (Bonnett, 2009)

Here, the prioritisation of lower risk species is at the cost of rarer and extinction is very likely a result. Many believe that the extinction of a species is a too higher price to pay. It has been argued that there is no scientific threshold at which we can designate a species as too far gone to save (Buckley, 2016). Species have come back from the brink of extinction before when they may have otherwise been abandoned under triage (Jachowski & Kesler, 2008). Other opponents argue that it is wrong to give up on saving a species because it is “economically expensive” suggesting it sets a dangerous precedent. In a scenario where conservation managers act to save only the species that are “efficient”, governments may be inclined to cut conservation funding leading to species being unnecessarily earmarked for extinction (Jachowski & Kesler, 2008).

Kākāpō

Under the conservation triage species with little chance of survival and a high cost of investment would often be set aside in favour of a cheaper, more secure one. This decision makes sense from a purely economic standpoint however many of these “expensive species” hold significant value to people. Kākāpō (Strigops habroptilus) are a critically endangered species of parrot with a population of less than 150. The remaining population is intensively managed under the Kākāpō recovery program. The recovery program has cost approximately $25 million NZD over 40 years and the species is still critically endangered (Jansen, 2006). Under a conservation triage model, one might argue that this is an inefficient use of conservation resources. The disinvestment in the kākāpō would likely lead to its extinction but would free up more funds to save other New Zealand species.

Kākāpō, Strigops habroptilus (Merton, 2001)

While New Zealand’s ability to protect other species would be greatly increased unforeseen impacts may occur if the kākāpō were to be left to fate. The loss of kākāpō under a triage scenario could lead to the loss of an important flagship species. Flagship species are creatures that people find cute or charismatic and are important in attracting conservation funding through donations (Walpole & Leader-Williams, 2002). Charismatic species like these are not just good advertisers of the plight of biodiversity. This species holds great value as a taonga species to iwi such as Ngai Tahu (Ngai Tahu, 2014) and is often considered one of New Zealand’s national natural icons. These social and cultural values cannot be forgotten when making decisions surrounding conservation.

Conclusion:

Conservation triage is a controversial approach to conservation management that has its pros and cons. There are many ways in which it can improve conservation success but there are also hidden costs and impacts that may not be considered. These are largely societal and cultural and may be difficult to anticipate or quantify. Here through the use of 3 examples, I hope to shed light on some of these issues in the hopes that we may find solutions to the conservation problem of prioritisation.

References:

Bonnett, R., (2009). “Female Sonoran Mud Turtle”. photo retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Female_Sonoran_Mud_Turtle_(3457438132).jpg

Bottrill, M., Joseph, L., Carwardine, J., Bode, M., Cook, C., Game, E., Grantham, H., Kark, S., Linke, S., McDonald-Madden, E., Pressey, R., Walker, S., Wilson, K., Possingham, H. (2008). Is conservation triage just smart decision making?. Trends in ecology & evolution, 23(12), 649-654.

Buckley, R. C. (2016). Triage approaches send adverse political signals for conservation. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 4, 39.

Forrest, S., (2007). “Woodland caribou in the Southern Selkirk Mountains of Idaho 2007”. Photo retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boreal_woodland_caribou#/media/File:Woodland_Caribou_Southern_Selkirk_Mountains_of_Idaho_2007.jpg

Hebblewhite, M. (2017). Billion dollar boreal woodland caribou and the biodiversity impacts of the global oil and gas industry. Biological Conservation, 206, 102-111.

Jachowski, D. S., & Kesler, D. C. (2009). Allowing extinction: should we let species go?. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 2919-2922.

Jansen, P. W. (2006). Kakapo recovery: The basis of decision-making. Notornis, 53(1), 184.

Kennedy, K., Aghababian, R. V., Gans, L., & Lewis, C. P. (1996). Triage: techniques and applications in decisionmaking. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 28(2), 136-144.

Merton, D., (2001). “Kakapo. 2-year-old male ‘Trevor’ feeding on ripe poroporo fruit. Maud Island, March 2001”. Photo retrieved from: http://nzbirdsonline.org.nz/species/kakapo

Ngai Tahu, (2014). Saving kākāpō. Retrieved from: https://ngaitahu.iwi.nz/our_stories/saving-kakapo/

Schneider, R., Hauer, G., Adamowicz, W., Boutin, S. (2010). Triage for conserving populations of threatened species: the case of woodland caribou in Alberta. Biological Conservation, 143(7), 1603-1611.

Soulé, M. E. (1985). What is conservation biology?. BioScience, 35(11), 727-734.

Stone, P. A., Congdon, J. D., & Smith, C. L. (2014). Conservation triage of Sonoran Mud Turtles (Kinosternon sonoriense). Herpetological Conservation and Biology, 9(3), 448-453.

Walpole, M. J., & Leader-Williams, N. (2002). Tourism and flagship species in conservation. Biodiversity and conservation, 11(3), 543-547.

The importance of value in species prioritisation – a holistic approach to the problem.

Posted: May 1, 2017 Filed under: 2017, ERES525 | Tags: conservation triage, noah's ark problem, PPP, prioritisation, species appeal, value Leave a commentBy Harry Stephens

Introduction

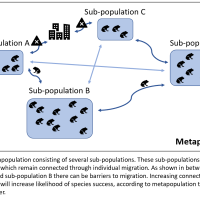

Discussion surrounding the ‘Noah’s Ark Problem’ (Weitzman 1998, Perry 2010, Small 2011) – a parable for conservation triage, has received heightened attention in recent years. This corresponds to an accelerated increase in species loss worldwide and subsequent costs associated with protecting many that are threatened (Butchart et al 2010). In conservation, ‘triage’ is the prioritisation of limited resources to maximise returns, relative to the goals, under a constrained budget (Bottrill et al 2008). Practically, it entails treating the ‘most valuable’ first, then dedicating fewer resources or abandoning the ‘less valuable’. The problem lies in taking values from an array of professional backgrounds, then determining comprehensive conservation objectives and management practices from these. Humans differ in their interest and attitude toward nature and naturally, approaches will be conflicting.

A traditional Noah’s ark scene from which modern day triage is based. Obtained from http://framingpainting.com/UploadPic/2010/big/Noah%27s%20ark.jpg.

The meaning of ‘value’

Fundamental to triage is recognition that scarce resources should not be wasted on the severely injured as they are unlikely to recover – we have to set priorities based on economic, ecological and aesthetic factors (Small 2011, Arponen 2012). There is not ‘one fits all’ criterion to determine where resources are allotted, as the definition of ‘conservation benefit’ depends on a various set of human values and beliefs. For example, the conservation scientist’s ‘value’ of a species generally refers to ecological or functional importance and is the key factor in prioritisation (Perry 2010). However, politicians may view a species based on economics, public expectation or aesthetics, sometimes dividing scientists and policy makers (Wittmer et al 2013). This has been observed in Australia and New Zealand, with the Office of Environment and Heritage and DOC respectively, demonstrating the difficulty in establishing an appropriate basis for decision-making around threatened species (Kilham and Reinecke 2015).

Science alone cannot dictate decision-making

Often, it has been suggested that prioritisation is not a scientific matter; rather it depends on what is valued (Arponen 2012). Furthermore, the fact that most funding for conservation comes from public sources (AEDA 2012), justifies people having more input into triage style decisions. Scientific research alone cannot be a robust foundation on which to implement conservation decisions, as it is based on imperfect information in a dynamic environment and thus, will always be questioned by political, economic and public bodies (Marris 2007, Kilham and Reinecke 2015). There is also uncertainty regarding species biology and population dynamics (Marris 2007, McDonald-Madden et al 2008, Arponen 2012), which has associated ecological risks like species interaction disruptions if science was to ‘get it wrong’. Even the most thoroughly studied organisms like Drosophila spp. have only been observed over a relatively short evolutionary time and there is still a lot to learn; the influence of a changing climate means that the cost and benefits of preserving species is also changing (Arponen 2012).

Species appeal and people power

Humans are programmed to like certain beautiful or decorative features of nature like flowers, fur, feathers and antlers (Small 2012). The idea of using charismatic or flagship species bearing these appealing characteristics to support other projects has received little acknowledgement from the scientific community (Andelman and Fagan 2000, Small 2012). A study by Brambilla et al (2013) on Italian bird species even suggested that conservation based on appeal could see species more susceptible to human influence from an Anthropogenic Allee Effect, exacerbating their threatened status.

However, species appeal may be the most effective driver in generating conservation dollars. Flagship, iconic and charismatic species like Grizzly bears (Ursus arctos), Californian Condors (Gymnogyps californiacus) and many large, African mammals may not have as much of a perceived value ecologically, but their appeal produces revenue from tourism and hunting, among other means (Arponen 2012). They also serve as highly visible examples of global conservation, and the public is willing to donate toward their management (Clough 2010, Small 2011). Indirectly, they are important for education and raising awareness which together increase the value of ecosystems and assist in funding projects for their more ecologically beneficial relatives (Perry 2010, Bennett et al 2015).

Conclusion

Just as Noah was limited by space aboard his Ark, decision makers are limited in the amount of biodiversity they can apply resources to. The ultimate objective is to preserve biodiversity, though the approach needs to equally recognize the biological, social and economic elements that reflect ideas of the involved parties. Tools like the Project Prioritisation Protocol (PPP) (Joseph et al 2008, Kilham and Reinecke 2015) are widely used and integrate these aspects based on trade-offs of ecological benefit, cost, success and species value resulting in a rank-ordered list of management actions. Inclusive tools such as the PPP are likely to become more common, as subjective and value-driven opinions concerning priority setting cannot be formed without unbiased consideration.

References

Andelman, S. J. and Fagan, W. F. 2000. Umbrellas and Flagships: Efficient Conservation Surrogates or Expensive Mistakes? National Academy of Sciences. (97) 11:5954-5959.

Applied Environmental Decision Analysis research hub (AEDA), 2012, On triage, public values and informed debate. Decision Point, No.65, p. 4.

Arponen, A. 2012. Prioritizing species for conservation planning. Biodivers Conserv 21:875-893

Bennett JR, Maloney R, Possingham HP. 2015 Biodiversity gains from efficient use of private sponsorship for flagship species conservation. Proc. R. Soc. B 282: 20142693

Bottrill M, Joseph LM, Carwardine J, Bode M, Cook C, et al. 2008 Is conservation triage just smart decision-making? Trends Ecol Evol 23: 649–654.

Brambilla, M., Gustin, M., Celada, C. 2013. Species appeal predicts conservation status. Biological Conservation 160:209-213.

Butchart, S.H.M., Walpole, M., Collen, B., van Strien, A., Scharlemann, J.P.W., Almond, R.E.A., Baillie, J.E.M., Bomhard, B., Brown, C., Bruno, J., Carpenter, K.E., Carr, G.M., Chanson, J., Chenery, A.M., Csirke, J., Davidson, N.C., Dentener, F., Foster, M., Galli, A., Galloway, J.N., Genovesi, P., Gregory, R.D., Hockings, M., Kapos, V., Lamarque, J.-F., Leverington, F., Loh, J., McGeoch, M.A., McRae, L., Minasyan, A.,

Hernández Morcillo, M., Oldfield, T.E.E., Pauly, D., Quader, S., Revenga, C., John, R., Sauer, J.R., Skolnik, B., Spear, D., Stanwell-Smith, D., Stuart, S.N., Symes, A., Tierney, M., Tyrrell, T.D., Vié, J.-C., Watson, R., 2010. Global biodiversity: indicators of recent declines. Science 328, 1164–1168.

Clough, P., 2010. Realistic valuations of our clean green assets. New Zealand Institute of Economic Res. NZIER 19/2010.

Joseph, L. N., Maloney, R. F., O’Connor, S. M., Cromarty, P., Jansen, P., Stephens, T. and Possingham, H. P. 2008. Improving methods for allocating resources among threatened species: the case for a new national approach in New Zealand. Pacific Conservation Biology. 14:3.

Kilham, E. and Reinecke, S. 2015. “Biggest bang for your buck”: Conservation triage and priority-setting for species management in Australia and New Zealand. Invaluable Policy brief 0115.

Marris, E. 2007. What to let go. Nature. (450) 8

McDonald-Madden, E., Baxter, P. W. J., Possingham, H. P. 2008. Making robust decisions for conservation with restricted money and knowledge. Journal of Applied Ecology, 45, 1630–1638

Perry, N. 2010. The ecological importance of species and the Noah’s Ark problem. Ecological Economics 69, 478–485

Small, E. 2011. The new Noah’s Ark: beautiful and useful species only. Part 1. Biodiversity conservation issues and priorities, Biodiversity, 12:4, 232-247,

Small, E. 2012. The new Noah’s Ark: beautiful and useful species only. Part 2. The chosen species, Biodiversity, 13:1, 37-53

Weitzman, M.L. 1998. The Noah’s Ark problem. Econometrica 66:6 1279-1298.

Wittmer, H. U., Serrouya, R., Elbroch, M. and Marshall, A., J. 2013. Conservation strategies for species affected by apparent competition. Conservation Biology. 27:2. 254-260.