The Relationship between Culture and Conservation in New Zealand

Posted: June 9, 2019 Filed under: 2019, conservation, Culture & Values, ERES525, Module Critique Assignment | Tags: co-management, Collaboration, conservation, culture, environment, native species, nature, Values Leave a commentBy Alice Hales

Abstract

Culture is born from living alongside one another. Traditions, customs, and social behaviours are the essence of our actions as individuals and communities (2). What we value, and why, determines what we are willing to preserve through conservation action. In New Zealand, collaboration between western ideologies and indigenous Maori perspectives are leading the way in co-management practices (12). Respecting the land, resources and species that inhabit it is close to the heart of Maori and the wider New Zealand community (12). Working together to share knowledge and find co-benefits is causing new policy to flourish. Acts such as Te Urawera and The New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy (2000-2020), incorporate Maori values (4, 13). Gaining stakeholder support, protecting the cultural identity of the tangata whenua, distribution of workload and mutual appreciation for areas or species are benefits of a co-management approach (4). Though culture can open doors to better biodiversity management, it can come with limitations. Cultural rituals or traditions may be harmful to conservation efforts, making it difficult to find a compromise (3). Conflicting values may induce conflict, often resolved by finding mutual goals and encompassing different views rather than shunning them.

Introduction

Humans living in community groups has given rise to traditions, customs, language and repeated social behaviours; this is human culture (2). Certain animal and plant species are treasured in different cultures; cows to Hindu, Morepork and black-backed gull to Maori, Tigers to Koreans, and so on (1). The species focused on in conservation, and the action taken, comes down to knowledge, values and local culture (3). In New Zealand, indigenous Māori communities are starting to have a significant contribution to conservation (12). Māori have a strong relationship to the land and endemic species, referring to it as an environmental whanaungatanga (familial relationship) (12).Without the support of locals, stakeholders and the wider community, there will be no funding for action (15). It is in the best interests of conservationists, and the community, alike to find co-benefits and co-values when considering management of a project (12).

Despite the positives, there are exceptions where culture can negatively impact conservation. Wildlife use or harvesting along with questionable practices can be overlooked if it of cultural value (3). Wayne Linklater, in a discussion on the culture of conservation in New Zealand, stated that conservation is improved when it involves a diversity of voices and values (10). Through mitigating the negative impacts, co-management works towards a positive future.

Culture in New Zealand

The base of New Zealand culture is a mix of western and indigenous Māori influence. Kaitiakitanga is a recognised term in policies and legislation; it encompasses the traditional guarding and stewardship for natural beings and resources by tangata whenua (Māori) (7). This concept is at the base of Māori culture; focusing on sustainability, preservation, utilisation and responsibility, rather than ownership (7). The image in figure 1 displays a Māori man holding a kiwi; a sacred species treasured by New Zealand.When European settlers and Māori communities signed the ‘Treaty of Waitangi’, it was agreed that relationships should be maintained, encouraged and respected to enhance conservation efforts (6). Proposals, use of traditional materials and protocols should be consulted in partnership with tangata whenua to retain cultural identity (6).

Figure 1. Māori man holding a kiwi. This species is sacred and treasured by all New Zealand cultures.

Effective Cooperation

The aim of New Zealand conservation is to preserve high levels of native/endemic biodiversity, while acknowledging and incorporating species, areas and practices sacred to the indigenous communities (6). This is reiterated in the The New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy (2000-2020), where valuing and understanding a Maori perspective is mentioned multiple times (4). Improving communication and encompassing Maori world views is essential for functional biodiversity strategies and gaining support from stakeholders, property owners and tangata whenua (4, 9).

The Te Urawera Act (2014) is leading the way in co-management and implementation of cultural values (5). Te Urawera is a forested area of great spiritual value to Māori and holds intrinsic value for all New Zealander’s (5). Collaboratively, groups came together and sought co-benefits; working together to conserve this special area (13). This act sets an example for revising and creating new legislation that sees Māori engagement as a beneficial asset (13).

Value judgements in conservation are difficult but necessary. Contention due to conflicting values can be resolved by finding a common ground. Like in the Te Urawera example, both Māori and the wider community value the forest highly (5, 13). Despite having different knowledge, skills and background, finding a co-value facilitated collaboration rather than conflict (8). Conservation needs to be about nature and culture; there is no evidence showing that education alters people’s values. So, the relationship between science and values in conserving a species or system needs open communication (11). It is often cultural influence and community interest that triggers the need for scientific research; this is a benefit of working together (11).

Room for Improvement

New Zealand is somewhat leading the world in conservation co-management, but there is room for improvement (9). Recently, Maori perspectives are being encompassed in proposals, but there are many acts that need updating. For example, Māori input was absent from both the Water & Soil Conservation Act 1967 and Clean Air Act 1972 (9). In the past conservationists were pessimistic about collaboration with indigenous perspectives. Alterations in management and policy take time, yet New Zealand is taking the right steps towards a better future for biodiversity (9).

Cultural views do not always align with conservation aims. Traditional practices, utilisation of natives and protecting certain species can be controversial (3). Many activities from different cultures involve killing or using animals for rituals and rites of passage; hunting, wearing their skins, consuming them or caging them (3). South African Nazareth Baptist Church kill and wear leopard (Panthera pardus) skins for religious gatherings, putting a strain on local populations (3). Cultural aspects can inhibit conservation efforts; for instance, the unsustainable harvesting of leopard skins is tolerated by many due to it being tradition (3). It is these limitations that emphasise the need for collaboration and consensus between different views (3).

Figure 2. The pacific rat, or Kiore. A treasured species of Māori people due to its long history of living alongside early New Zealanders.

In New Zealand, the Pacific rat, or kiore, (Rattus exulans) is considered taonga (treasured) to some Māori. Rodents and introduced mammals threaten native species; conservationists have plans and action to eradicate the pests (14). These conflicting values meant a compromise needed to be made to resolve the issue. Māori treasure endemic species as well as wanting to conserve the kiore (pictured in Figure 2). A decision was made to move populations of the rats to offshore islands (with local Māori management and regulation) where they will be of less threat to endangered native species (14). This is in accordance with “Predator-Free 2050” where the New Zealand government is set to eradicate all rats, mustelids and possums from the mainland (14).

This example illustrates the difficulties when combining culture, values and knowledge in conservation. Not all practices will be beneficial to species or the environment, but it is essential to find co-benefits and ways to mitigate as much negative impact as possible.

Conclusion

Cultural identity, knowledge and values all go hand in hand in relation to conservation (2). In New Zealand, indigenous support and guidance for proposals and actions is beginning to take precedence (12). It is common to see co-management and collaboration between Māori and conservationists; legislation such as Te Urawera and The New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy (2000-2020) emphasise the importance of maintaining culture in all things (4, 13). Losing culture along with biodiversity is not an option in New Zealand, although many outdated policies are yet to be corrected.

Culture can heavily influence opinions. Though culture can open doors to better biodiversity management, it can come with limitations. An action may go against conservationist’s plan for a species, as many rituals and practices involve animal species (3). Coming to a consensus on the best way to preserve culture while protecting biodiversity mitigates negative outcomes. Indigenous knowledge is invaluable to conservation in New Zealand and in gaining nation-wide support.

References

- Animal Sciences. (2019). Cultures and Animals. Retrieved from:https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/cultures-and-animals

- Brown, D. E. (2004). Human universals, human nature & human culture. Daedalus, 133(4), 47-54.

- Dickman, A., Johnson, P. J., Van Kesteren, F. & Macdonald, D. W. (2015). The moral basis for conservation: how is it affected by culture? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment,13(6), 325- 331.

- (2000). New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy 2000-2020. Retrieved from: https://www.doc.govt.nz/globalassets/documents/conservation/new-zealand-biodiversity-strategy-2000.pdf

- (2014). Te Urewera Act 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2014/0051/20.0/whole.html#DLM6183611

- (1987). Treaty of Waitangi Responsibilities. Retrieved from: https://www.doc.govt.nz/about-us/our-policies-and-plans/conservation-general-policy/2-treaty-of-waitangi-responsibilities/

- Environment Guide. (2018). What is kaitiakitanga? Retrieved from: http://www.environmentguide.org.nz/issues/marine/kaitiakitanga/what-is-kaitiakitanga/

- Gavin, M. C., McCarter, J., Mead, A., Berkes, F., Stepp, J. R, Paterson, D. & Tang, R. (2015). Defining biocultural approaches to conservation biology. Opinion, 30(3), 140-145.

- Jay, M. (2005). Recent changes to conservation of New Zealand’s native biodiversity. New Zealand Geographer, 61, 131-138.

- Linklater, W. (2019). The Culture of Conservation in New Zealand. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WYDM4yjFTo4

- Mace, G. M. (2014). Whose conservation? Science, 345(6204), 1558-1560.

- Mere, R., Waerete, N., Nganeko, M. & Del Kirkwood Carmen, W. (1995) Kaitiakitanga: Maori perspectives on conservation.Pacific Conservation Biology, 2, 7-20.

- Ruru, J., Lyver, P. O’B., Scott, N. & Edmunds, D. (2017). Reversing the Decline in New Zealand’s -Biodiversity empowering Maori within reformed conservation law. Policy Quarterly, 13(2), 65-71.

Bridging the Science-Culture Gap

Posted: June 7, 2019 Filed under: 2019, conservation, ERES525, Module Critique Assignment, Uncategorized | Tags: culture, environment, humans, nature Leave a commentIsaac Weaver (300392153)

Hinduism states the Ganges river is of divine origin. Having been blessed by the three supreme gods, the Ganges known as the goddess Ganga “the purifier” has the power to cleanse all sins. This belief makes dealing with the pollution issues that faces the Ganges difficult. Many Hindus are unwilling to accept that Ganges (the sacred embodiment of Ganga) could be impure or polluted. However, the high levels of toxic heavy metal and biological waste is a substantial public health risk. The government of India has tried to solve the issue through the Namami Ganga Programme (NGP) but has failed. The failure results from a lack of support from the people for the building of sewage treatment facilities. However, the NGP has been successful at bridging the gap between culture and science. The NGP has used religious ceremony to communicate environmental awareness to a previously unreceptive audience. These ceremonies tie scientific principles with culture and spirituality and may help the NGP gain much-needed momentum.

Introduction

The Ganges or Ganga river flows from the western Himalayas to the Bay of Bengal. The 2525km long river is spiritually and culturally significant to the people that live alongside it. The river is worshipped as the goddess Ganga “the purifier” in Hinduism. However, Ganges is one of the world’s most polluted freshwater systems. In the rise of India’s role as a world superpower the urbanisation and industrialisation of lands aside the Ganges has boomed (Troch, 2018.) The waste from urban and industrial areas are dumped into the Ganges leading to increases in pathogenic bacteria and toxic heavy metals. The river is also full of human and other animal corpses from religious ceremonies (Jaiswal et al., 2017). To clean the Ganges, the Government of India (GoI) launched the USD 3 Billion Namami Gange Programme (NGP) (Mukherjee, 2019.) However, devout Hindus believe that the water cannot be impure and to suggest that it is has been a contentious issue for the GoI. To overcome the controversial nature of the issue, the GoI’s Namami Ganga programme has engaged in cultural outreach through the use of religious ceremonies and religious officials.

The Ganges Religious Origin

The Ganges River is one of the most sacred sites in Hinduism and was formed during the Avatarana (Descent of Ganga). It is said to originate from the three supreme gods, the creator, the destroyer and the preserver. The legend begins when Lord Vishnu (the preserver) attempted to measure the universe with his left leg. With his foot extended, his toenail punctured a hole in the edge of the universe, allowing divine water to enter the universe as the Goddess Ganga. The pink hue of the Ganges is said to be caused by saffron washed off the feet of Lord Vishnu. The water depicted as the goddess Ganga then flows into the realm of Lord Brahma (the creator). Brahma then sends Ganga to earth to purify the people of King Bhagiratha. Insulted Ganga tried to destroy all life on earth. However, before reaching earth, Ganga is trapped by Lord Shiva (the destroyer). To protect, the earth Ganga is released in streams of purifying holy water which formed the Ganges River (Eck,1998.)

The Avatarana (descent of Ganga) painting by Raja Ravi Varma https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ganges

Culture and Science

Many Hindus do not accept that the river Ganges is polluted. To Hindus the river known as the goddess Ganga Ma, who is the purifier or mother. Because the water has passed through and touched the three supreme gods, it is considered extremely sacred. Bathing in the river pays homage to ancestors, gods and purifies the soul. The Ganga is also seen as a way to ascend into Swarga (Hindu Heaven) (Luthy, 2019). In the city of Varanasi, bodies are cremated on the stepped banks (Ghats) of the Ganges, and the ashes pushed into the waters (McDonald, 2018.) This ritual results in the deceased being absolved of all sins escaping reincarnation and being honoured in Swarga. The water of the Ganges is known as Ganga Jal (Ganga’s holy water.) It is said to have a sacred cleansing ability to wash away sin and improve health (Bhargava, 2014). Therefore, calling the water polluted and in need of cleaning has been contentious (Das & Tamminga 2012; Kedzior, 2014.)

B.D. Tripathi former member of the National Ganga River Basin Authority (NGRBA). The NGRBA is the authority in charge of the NGP river clean up. In this interview B.D. Tripathi promotes the mythological benefits of drinking Ganga Jal although it is not deemed fit for human consumption. (VICE, 2019)

However, the Ganges River is highly polluted with biological and toxic heavy metal wastes. 2550 million litres per day (MLD) of raw sewage is pumped directly into the Ganges river. Furthermore, it is estimated that over 100,000 human bodies are partially cremated and pushed into the river. This results in high levels of bacteria per unit of water, which is unsafe for human consumption and bathing (Zhang et al., 2019). The largest polluters of heavy metal wastes along the Ganges are the Tanneries in the city of Kanpur. Over 264 tanneries are producing between 5.8 and 8.8 MLD of wastewater (Chaudhary & Walker, 2019.) These tanneries produce a high level of chromium, a heavy metal associated with developmental disorders, kidney damage and liver cancer. These tanneries also produce high levels of cadmium, zinc and mercury. The river sediments show high levels of toxic waste accumulation and the fish show high levels of bioaccumulation (Tripathi et al.,2017.) The toxic waste accumulation in the sediments and fish and the high levels of faecal matter and bacteria makes the Ganges one of the most highly polluted freshwater systems in the world.

Kanpur sewerage outflow directly into the Ganges producing 150 MLD of wastewater (VICE, 2019)

Cultural Outreach (NGP)

Critics of the Namami Ganga programme have argued that it is a failure. The program was initially set up to build treatment facilities to reduce pollution from sewerage. The programme has spent USD 205 Million in 3 years and build no treatment facilities, as they have had to fight corruption and lack of support from the people (Natarajan, 2016; Rahman, 2017.) However, the programme has been successful at public engagement bringing culture and science together.

Through religious ceremonies and religious officials, the GoI are bringing ancient Hindu culture and modern science together (Luthy, 2019.) Spiritual Gurus can reach millions of devoted followers that government environmentalist has failed to engage. The GoI has been working with ashram (spiritual hermitage/ monastery) to raise awareness through Ganga aarti (Sacred ritual honouring Ganga). Ganga aarti is a spiritual ceremony conducted to honour the goddess Ganga and engage the senses. It involves singing, speeches, incense, dance, lights, giving of divine gifts, offerings and many means of stimulating the senses (Zara, 2015.) With senses stimulated, spiritual Gurus install the virtues of environmental awareness through sacred ritual.

The Parmarth Niketan ashram regularly practices environmental focussed Ganga aarti. One method this ashram has employed through Ganga aarti is to invite notable environmentalists like Vijaypal “Green Man” Baghel to speak at Ganga aarti. These speakers are welcomed onto the ashram through a ritual ceremony involving giving of a divine gift. Furthermore, the gurus, like Pujya Swami Chidanand Saraswatiji of Parmarth Niketan ashram, then utter panegyric praise supporting the speaker (Luthy, 2019.) This opens the cultural dialogue and allows the speaker to communicate a scientific message to a historically unreceptive audience (Kedzior, 2014.) The spiritual engagement and scientific communication at the Ganga aarti evoke a more profound reverence for the Ganges and inspire the need for environmental action (Singh, 2016).

Pujya Swami Chidanand Saraswatiji (Center) of Parmarth Niketan ashram leading fire ceremony of the Ganga aarti to show reverence for Ganga. (NPR, 2017)

Conclusion

Cultural belief and science do not always go together well. The Ganges river is severely polluted. The high levels of bacteria and toxic accumulation poses a massive threat to public health. Considering 25% of India’s water resources are derived from the Ganges, there is potential for disaster. However, Hindus believe the divine origins of the Ganges means that it can never be impure. To suggest that the Ganga is polluted has been contentious. The controversial nature has meant the NGP has been ineffective and failed to build any infostructure to solve the pollution issue. Where the programme has been successful in breaking down cultural barriers and communicating science to a new and critical audience. Hindus. By making scientific issues like heavy metal and biological pollution, a cultural and spiritual issue, the NGP might gain momentum. This momentum will be essential to help protect the polluted purifier.

References

Bhargava, D. S. (2014). Nature’s Cure of the Ganga: The Ganga-Jal. In Our National River Ganga (pp. 171-188). Springer, Cham.

Chaudhary, M., & Walker, T. R. (2019). River Ganga pollution: Causes and failed management plans (correspondence on Dwivedi et al. 2018. Ganga water pollution: A potential health threat to inhabitants of Ganga basin. Environment International 117, 327–338). Environment international, 126, 202-206.

Das, P., & Tamminga, K. R. (2012). The Ganges and the GAP: an assessment of efforts to clean a sacred river. Sustainability, 4(8), 1647-1668.

Eck, D.(1998), “Gangā: The Goddess Ganges in Hindu Sacred Geography”, in Hawley, John Stratton; Wulff, Donna Marie (eds.), Devī: Goddesses of India, University of California / Motilal Banarasidass, pp. 137–53, ISBN 978-8120814912

Jaiswal, S. K., Gupta, V. K., Maurya, A., & Singh, R. (2017). Changes in water quality index of different Ghats of Ganges River in Patna. International Journal of Emerging Trends in Science & Technology, 4(08), 5549-5555.

Kedzior, S. B. (2014). Ganga: the benevolent purifier under siege. Nidan: International Journal for Indian Studies, 26(2), 20-43.

Luthy, T. (2019). Bhajan on the Banks of the Ganga: Increasing Environmental Awareness via Devotional Practice. Journal of Dharma Studies, 1-12.

McDonald, J. (2018). Life and death in the holy city of Varanasi and the state of the Ganges. Arena Magazine (Fitzroy, Vic), (154), 26.

Mukherjee, M. (2019). Agenda Setting in India: Examining the Ganges Pollution Control Program Through the Lens of Multiple Streams Framework. In Public Policy Research in the Global South (pp. 231-246). Springer, Cham.

Natarajan, P. M., Kallolikar, S., & Ganesh, S. (2016). Transforming Ganges to be a living river through waste water management. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, International Journal of Environmental, Chemical, Ecological, Geological and Geophysical Engineering, 10(2), 251-260.

NPR. (2016) – https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2017/07/02/535017334/will-giving-the-ganges-human-rights-protect-the-polluted-river

Rahman, A. (2017). Exploitation and rejuvenation of River Ganges: polices, institutions and governance. In Proceedings of 1st International Conference on Water and Environmental Engineering (iCWEE), Sydney, Australia, 20-22 November, 2017 (pp. 28-37).

Singh, R. (2016). Cultural and scientific aspect of river Ganga. Indian Journal of Life Sciences, 5(2), 119-123.

Tripathi, A., Kumar, N., & Chauhan, D. K. (2017). Understanding Integrated Impacts of Climate Change and Pollution on Ganges River System: A Mini Review on Biological Effects, Knowledge Gaps and Research Needs. SM J Biol, 3(1), 1017.

Troch, M. (2018). Impact of urban activity on Ganges water quality and ecology: case study Kanpur.

VICE, (2019) – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v8lu9ntmPJo&t=352s

Zara, C. (2015). Rethinking the tourist gaze through the Hindu eyes: The Ganga Aarti celebration in Varanasi, India. Tourist Studies, 15(1), 27-45.

Zhang, S. Y., Tsementzi, D., Hatt, J. K., Bivins, A., Khelurkar, N., Brown, J., … & Konstantinidis, K. T. (2019). Intensive allochthonous inputs along the Ganges River and their effect on microbial community composition and dynamics. Environmental microbiology, 21(1), 182-196.

Gaia Theory and its Contribution to Conservation

Posted: April 12, 2019 Filed under: 2019, ERES525, Module Critique Assignment, Uncategorized | Tags: ecology, environment, Gaia, humans, nature, sustainability, theory Leave a commentby Liam McAuliffe

The Blue Marble: Apollo 17 crew. December 17th 1972

Abstract

The Gaia theory identifies the relationships between living and non-living aspects of the world, and how these systems feed back into one another. As such, Gaia theory functions as a global extension of key ecological and biogeographical theories. This essay explores how the implication of Gaia theory in conservation of species and communities. This essay first addresses common critiques of Gaian theory, and how Gaia theory remains relevant despite these critiques. This essay then demonstrates how Gaia theory builds understanding of the regulatory functions of the non-living and living world, which in turn allows us to better identify and predict issues of global change. The outcome of this is the ability to create more effective recovery plans for species and communities as a result.

Introduction

The belief that Earth is a living system has been found throughout humanity for millennia (Vane-Wright & Coppock, 2009). Now science is finding its place in this concept. The Gaia theory identifies that life requires specific conditions to exist and Earth’s atmosphere remains balanced around these conditions (Lovelock, 1979). The Gaian Earth, comprised of its crust, climate, ocean and atmosphere, is constantly regulated by living organisms to be continually habitable for living organisms (Lovelock, 1979; Simpson, 1989).

Gaia theory essentially functions as an extended version of core biogeographical and ecological theories, on a global scale. Theories which demonstrate relationships between living and non-living aspects of the world, such as biosphere theories and systems ecology, are key components of Gaian principles (Gribben, 1990; Schwartzman, 2002; Turney, 2003). Gaia theory takes these spatially restricted theories and applies them to a global setting, and through this becomes more relevant to worldwide issues, such as the biological responses to climate change.

This essay will explore the implication of Gaia theory in species and community recovery. Firstly, this essay will address critiques of Gaian theory, and how Gaia theory remains relevant despite these critiques. Subsequently, this essay will demonstrate how understanding the regulatory functions of the non-living and living world allow us to better identify and predict issues of global change and create more effective recovery plans as a result. By doing so, this essay will demonstrate how Gaia theory continues to contribute to conservation biology which in turn allows more efficient species and community restoration.

Relevance of Gaia Theory

Gaia theory can be summarised in three main points; feedback loops contribute to a homeostatic system, this system makes the environment habitable by life, and that this system is brought about by natural selection (Kirchner, 2002, 2003).

These core aspects of Gaian theory are often criticised for their inaccuracy and over-generalisation of complicated systems that are constantly changing (Kirchner, 2002, 2003). Critics state that the Earth only appears to be a self-regulating homeostatic system because natural selection partially responds to changes in the environment, but this is to increase reproductive success not to feed back into a Gaian system (Kirchner, 2002, 2003). Additionally, critics demonstrate how great changes in the Earth’s atmosphere and climate, such as we are seeing now, indicate that the Earth’s systems are not homeostatic and that adaptive responses in species will be to amplify these changes and not reduce them (Simpson, 1989; Kirchner, 2002, 2003; Bazzaz, 1990).

However, many ecologists (including critics of Gaia theory), observe that there is a need for a large-scale ecological theory to identify what issues are inhibiting species and community recovery globally (Kirchner, 2002, 2003).

Gaia theory demonstrates how the non-living world and the living world feed back into one another, and this in turn explains how changes in one has effects on the other. Regardless of the accuracy behind a perfectly homeostatic Earth suggested by Gaia theory, the core message behind the theory functions as a global extension of key ecological and biogeographical theories (Gribben, 1990; Schwartzman, 2002; Turney, 2003). As a result of this, it fulfills the need for a large-scale theory to increase understanding of worldwide issues, and through this continues to be a useful tool for species and community recovery.

Gaia as an Indicator of Change

Ecosystems are changing more rapidly than they have for thousands of years, with higher rates of extinction, and native ranges of species shifting to more habitable climates (Simpson, 1989; Bazzaz, 1990; Cafaro, 2015; Kaur & Bhatia, 2018; Ünal et al., 2018; Maguire et al., 2019).

These biological responses often stem from changes in the non-living world, such as deforestation, the burning of fossil fuels, and the rise in CO2, which contribute to a changing climate (Simpson, 1989; Staniforth, 2007; Vane-Wright & Coppock, 2009).

Gaia theory emphasises Earth’s homeostatic norm and identifying divergence from this norm allows a deeper understanding of climate change and an explanation of global ecosystem responses (Simpson, 1989; Bazzaz, 1990; Cafaro, 2015; Kaur & Bhatia, 2018; Ünal et al., 2018; Maguire et al., 2019).

This is an important first step in the conservation of species and communities as it allows the capacity to construct more efficient recovery plans which address the issues identified by divergence from a homeostatic norm (Lovelock, 1979; Bazzaz, 1990; Staniforth, 2007; Cafaro, 2015).

Additionally, this allows Gaia theory to function as a predictive tool for future biological responses to changes in the non-living world (Lovelock, 1979). Understanding potential future changes in the non-living world will allow better foresight into species and community conservation that are more efficient and have an increased longevity. This will be of particular importance when creating recovery plans for species that may have shifts in their native ranges as a result of global temperature changes (Bazzaz, 1990).

For these reasons, Gaian theory remains relevant in modern conservation, regardless of its accuracy of a perfectly homeostatic world. Through its extension of key ecological theories, Gaia theory allows us to better understand current causes of species and community declines, and create more effective recovery plans as a response.

Conclusion

Gaia theory is not required to be true for it to continue to be useful for conservation. The key message from the theory is that the non-living and living world feed into one another, which explains why changes in one has dramatic effects on the other. By doing this, Gaia theory fulfills a gap in our conservation understanding, which is how we extend current ecological and biogeographical theories to a global stage.

This essay has demonstrated that there are critiques of Gaia theory, but how addressing these critiques allows us to better identify and predict global changes, and the issues these may cause for the living world. This in turn allows us to make more informed and effective plans for species and community recovery.

By adding Gaia theory to our conservation toolbox, we gain the opportunity to make more effective restoration decisions, which emphasise the relationships between non-living and living worlds from a global perspective.

References

Bazzaz, F. A. (1990). The response of natural ecosystems to the rising global CO2 levels. Annual review of ecology and systematics, 21(1), 167-196.

Cafaro, P. (2015). Three ways to think about the sixth mass extinction. Biological Conservation, 192, 387-393.

Gribben, J. Hothouse Earth: The Greenhouse Effect and GAIA, 1990. Grove Weidenfeld, New York.

Kaur, M., & Bhatia, A. (2018). The impact of Consumer Awareness on buying behavior of green products. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management, 6(04).

Kirchner, J. W. (2002). The Gaia hypothesis: fact, theory, and wishful thinking. Climatic change, 52(4), 391-408.

Kirchner, J. W. (2003). The Gaia hypothesis: conjectures and refutations. Climatic Change, 58(1-2), 21-45.

Lovelock, G. (1979). A new look at life on earth. New York.

Maguire, R., Johnson, H., Taboada, M. B., Barner, L., & Caldwell, G. A. (2019). A review of Single-use Plastic Waste Policy in 2018: What will 2019 hold in store?.

Schwartzman, D. (2002). Life, temperature, and the Earth: the self-organizing biosphere. Columbia University Press.

Simpson, P. (1989). Science and research internal report n0.49 the sweet one hundred. Department of Conservation.

Staniforth, S. (2007). Conservation heating to Slow Conservation: A tale of the appropriate rather than the ideal. The Getty Conservation Institute.

Turney, J. (2003). Lovelock and Gaia: signs of life. Columbia University Press.

Ünal, A. B., Steg, L., & Gorsira, M. (2018). Values versus environmental knowledge as triggers of a process of activation of personal norms for eco-driving. Environment and behavior, 50(10), 1092-1118.

Vane-Wright, R. I., & Coppock, J. (2009). Planetary awareness, worldviews and the conservation of biodiversity. The Coming Transformation. Values to Sustain Human and Natural Communities. Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, New Haven, 353-382.

Shall we reconcile?

Posted: March 22, 2019 Filed under: 2019, conservation, ecology, ERES525, Module Critique Assignment | Tags: #reconciliation, #togetherness, ecology, environment, nature, peace, value Leave a commentAbhijeetkumar

Abstract

Applied ecology draws concepts and ideas from the science of ecology for policy setting, decision making, and practice to solve contemporary problems in managing our natural resources [1].

Restoration, Reservation and Reconciliation form three important pillars of applied ecology.

With an anthropocene extinction close at our heels, conservationists are faced with many dilemmas to save species and ecosystems.

In the words of Baba Dioum “In the end we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught.”

With more areas being occupied by urban spaces than ever before, and most humans living in urban settings, it is essential to integrate nature with people and fulfill their biophilic needs.

In this paper, we describe all the three R’s of ecology (Restoration, Reservation and Reconciliation) and provide case studies of how reconciliation ecology is proving to be a biodiversity boon.

Introduction

Humans are completely dependent on nature to fulfill all their needs. A fight for nature is thus a fight for humans.

“The total area covered by the world’s cities is set to triple in the next 40 years – eating up farmlands and threatening the planet’s sustainability” [2]

Shanghai in China, one of three countries where 37% of all future urban growth is expected to take place. Photo Credit: Philipus/Alamy

In this paper, we discuss how restoration and reservation have an important role to play in conservation but have limited reach and how reconciliation, on the other hand, emerges as conservation hero with its far reach and ease of application in urban settings where most of the world’s human populations reside.

Reservation

Large reserves are a safety net against unanticipated ecological consequences because they are relatively free from human disturbances. [2]

Pench Tiger Reserve

Photos courtesy: Madhya Pradesh Forest Department, India.

An example of successful reservation is Project Tiger in India, administrated by the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) governing 50 tiger reserves. Today, India is home to 70% of the world’s tigers and the growth figures look encouraging.

Data Source: World Wildlife Fund and Global Tiger Forum.

Reservation demands land which is already scarce. Locals often see it as a displacement of their homes and livelihoods building resentment in them. While reservation may increase eco-tourism and jobs related to it, the question of whether it is the most profitable use of the land often drives political and social thinking, especially for landowners.

Restoration

Ecological restoration is the process of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged or destroyed. [5]

Restoration projects tend to be small-scale as large-scale projects require heavy funding. Project goals and decisions are often tied to the degree of aspiration and resources available as well as to the extent of degradation to the site and the surrounding landscape.

Restoration projects are complex, take long periods of time and whether we can really restore an ecosystem to pristine is debatable. To be successful, restoration requires political alignment, realistic goal and objectives, cost-benefit analysis and financial support [4] making them difficult to implement and evaluate.

Reconciliation

According to Dr. Rosenzweig “reconciliation ecology is the science of inventing, establishing and maintaining new habitats to conserve species diversity in places where people live, work and play.”

By its mere definition, two things stand out, it can be done everywhere by people in their own habitats and it helps build diversity. Its beauty and effectiveness thus lie in its simplicity.

Gaia Vince says “Urban areas could be the best hope for the survival of many species, but to do so we need to incorporate the natural world in new and innovative ways.”

According to a theory of the biologist E. O. Wilson, biophilia is an innate and genetically determined affinity of human beings with the natural world. The Biophilic Cities Project has worked with cities like San Francisco in the United States, Singapore, Wellington in New Zealand, and Birmingham in the United Kingdom to explore the different ways a city could be biophilic. [8]

For example, Tucsonans have made a conscious effort to share their city space with native birds and provide bird habitats right within their own habitat. (Tucson Bird Count)

Sometimes sharing is accidental and sometimes it is purposeful but, in both cases, it works and is quite cheap. [6]

Example: The Turkey Point power station, Miami.

To cool the hot effluent of the nuclear reactor, Florida Power and Light gouged 80 miles of giant cooling canals into the adjacent land. A rare species of saltwater crocodile moved flourished here. Instead of slaughtering them, the company hired a permanent team of biologists to make the new habitat even more croc-friendly. [9]

Biologist Mario Aldecoa, holds a handful of crocodile hatchlings he captured near the Turkey Point Nuclear Power Plant in Homstead, Fla. Picture credits: Wilfredo Lee/AP

“Does reconciliation make money or cost money?”

In many cases, reconciliation may not just be cheap but actually create sources of income such as the Red Sea Star Restaurant in Eliat, Israel. [6]In this case, builders saved money and the birds were saved. Today’s salt marsh resembles a natural habitat on a refuse dump and produces wildlife food at four times the rate of a natural salt marsh. [6]

Conclusion

Since large mammals will never be able to make cities their homes and many ecosystems are malfunctioning due to human interventions, restoration and reservation will continue to play a key conservation role. However, these efforts are expensive, time-consuming require political alignment and funding and have limited scope as they cannot be applied everywhere.

The 6th mass extinction is a real threat that can be altered by promoting biodiversity. “Increasingly we should turn to reconciliation ecology because avoiding the impending mass extinction will require employing it extensively” [6]. As more cities dot the global map and hold most of the world’s human population, reconciliation ecology emerges as a game changer to make humans connect with nature and promote biodiversity.

Can we stop the urban sprawl, I think not, but can we bring nature back to cities, the answer is definitely yes and reconciliation is the everyday urban superhero poised to do it.

Reconciliation the Conversation Hero

Photo Credit: DC Comics

Every urban citizen can don the reconciliation cape with little effort and investment.

Saalumarada Thimmakka a 106-year-old lady of very modest means, was awarded India’s fourth highest civilian award for her tireless effort to make the planet green by planting 8000 trees in 80 years. [10]

This is proof of the concept that “Reconciliation ecology thrives incrementally. It does not require the grand design, the universally accepted paradigm. Every little contribution can add meaningfully to the dream.” [6]

Indian President Ram Nath Kovindsaid “At the Padma awards ceremony, it is the President’s privilege to honour India’s best and most deserving. But today I was deeply touched when Saalumarada Thimmakka, an environmentalist from Karnataka and at 107 the oldest Padma awardee this year, thought it fit to bless me”

Photo Credit: PTI

References

- Georges, L.J. Hone, R.H. Norris, Applied Ecology, Encyclopedia of Ecology 2008, Pages 227-232, available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978008045405400848X

- Lindenmayer, D.; Burgman, M. A. (2005) Practical conservation biology. Chapter 4 in Practical conservation biology pp. 87—119.

- Mark Swilling, The curse of urban sprawl: how cities grow, and why this has to change, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/jul/12/urban-sprawl-how-cities-grow-change-sustainability-urban-age

- Rohr, Jason R et al. “Transforming ecosystems: When, where, and how to restore contaminated sites.” Integrated environmental assessment and management vol. 12,2 (2016): 273-83. doi:10.1002/ieam.1668

- Clewell AF, Aronson J (2013) Ecological restoration: principles, values, and structure of an emerging profession. 2nd edition. Island Press, Washington, D.C

- Rosenzweig, L. G. (2003) Win Win Ecology: How the earth’s species can survive in the midst of human enterprise. Oxford University Press, 7-89.

- Gaia Vince, Why we need to bring nature back into cities, BBC: http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20130530-bringing-nature-back-into-cities

- Tim Beatley , Geodesigning Nature into Cities, available at https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/arcnews/geodesigning-nature-into-cities/?rmedium=arcnews&rsource=https://www.esri.com/esri-news/arcnews/winter16articles/geodesigning-nature-into-cities

- Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Ecologist Urges Sharing Land with Other Species to Foster Biodiversity, available at https://www.jhsph.edu/news/stories/2004/reconciliation.html

- Madur, Saalumarada Thimmakka – The Green Crusader, 2019, available at https://www.karnataka.com/personalities/saalumarada-thimmakka/

- Public Affairs Media Contacts for the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: Tim Parsons or Kenna Brigham (7 March 2004) Extracted from: https://www.verywellmind.com/how-to-reference-articles-in-apa-format-2794849

Cost vs. Benefit: Determining an efficient way forward for Conservation Ecology

Posted: March 20, 2019 Filed under: 2019, conservation, ecology, ERES525, Module Critique Assignment | Tags: conservation, ecology, economics, environment, humans, nature, reconciliation ecology, reservation, restoration ecology Leave a commentBy Jess Shute

Abstract

Cost versus benefit is a highly motivating aspect of society and often plays a key role in the adoption of new techniques, approaches and practices. As the world is faced with increasing concerns of biodiversity loss and climate change effects, the way forward for conservation practice is widely debated. The role of Reservation, Restoration and Reconciliation ecology are here evaluated in terms of their power to affect change in relation to this cost/benefit relationship. The approach that requires the smallest of capital investment and the most monetary reward will be considered to be the most appropriate way forward for ecological practice.

Figure 1. Conceptual image of the relationship between money & nature. (Fotalia, n.d.)

Introduction

Economic benefit, defined as the exchange of goods for money, as an incentive for change will here be used to discuss the goal of reaching a viable coexistence between nature and humans. The idea of monetary gain as a motivational driver does not represent every individual, however, it is important to consider the old adage of ‘money makes the world go round’.

Humans desire rewards for their work and the most basic form of reward is the wage they earn for it. As such, money may provide an effective incentive to alter behaviours and strive for sustainability. As conservationists, how can we use this as a tool? If economic benefit is a significant driver in human endeavour, which of the three Rs (Reconciliation, Reservation or Restoration) garner the most support in achieving a sustainable future?

Reservation is comparatively cheap but, in most cases, offers little to no economic value in return. Restoration is a costly endeavour and requires ongoing maintenance which can be seen as a drain rather than a benefit. Reconciliation, by contrast, offers a ‘win-win’ situation. Although it requires some initial capital investment to implement the changes needed, a continued return from shared land use is commonly gained. Consequently, I argue that Reconciliation is the most effective ecological approach in ensuring human behavioural changes occur to avoid the exhaustive natural resource extraction practices (Miller et al, 2014) currently leading us toward irreparable damage. Humankind is irrefutably part of the problem, and unarguably must be part of the solution. But what is the most persuasive solution?

Reservation

Balmford (et al. 2002) reports that a worldwide network of nature reserves would cost approximately $45 billion/year to maintain, and is therefore unlikely to incentivise a synergistic coexistence between humans and the environment. It has been proposed that Reservation is not an effective way to preserve ecosystems for two major reasons. Firstly, it disadvantages an ecosystem in adapting by artificially halting the natural evolutionary processes (Thomas, 2017). Humans are a global species. There is no environment that we have not reached, influenced or affected. It is understood that even the wildest areas have been touched by humankind (Marris, 2011), and I argue that the ongoing support required by these reservations that will never develop in a way to support themselves is, in itself, unsustainable.

Figure 2. Graph showing the negative and positive effects of all significant fragmentation across all ecological responses (Fahrig, 2017).

Secondly, evidence suggests that the isolation of large swathes of land is not the most appropriate way to encourage and support biodiversity. Fahrig (2017) suggests that fragmentation, on a landscape scale, is often associated with more positive effects than traditionally perceived. From an analysis (Fahrig, 2017) of 118 independent studies, just 24% exhibited negative reactions to the changes, while the remaining 76% reacted positively to habitat fragmentation (see Figure 2), contrary to popular belief and intuitive assessment. By setting aside land, we restrict human use/benefits. If this works against natures natural development and provides no resources to support anthropic endeavours, then reserves as a ‘natural time capsule’ are counterproductive, wasteful, and unsustainable.

Restoration

Restoration ecology battles baseline issues and involves substantial initial cost and ongoing maintenance which create a drain on the local economy (Colston, 2003). Baselines depend entirely on perspective. For example, colonials viewed the Americas as pristine (Marris, 2011), whereas the landscape had been vastly altered by the arrival by the first peoples centuries prior. In settling on a baseline, it is then a matter of restoring the concerned habitat to that arbitrary baseline. The initial costs of which are phenomenal (Kimball et al., 2015), although Verdone (2015) argues against this standpoint, and instead proposes there is a monetary benefit in restoration though it seems the main aim is to repurpose the land for productive use in the future, not to re-establish a lost ecosystem.

As anthropogenic effects are constantly affecting the environment the ongoing costs associated with maintenance of a restoration project are endless and in a sense unachievable. Environments are constantly in flux from natural selection pressures, and thus one cannot maintain a constant if the natural way is not constant itself (Thomas, 2011), I refer here to environmental dynamism. Restoration as an approach also offers a poor incentive for local communities working on smaller economic scales to adopt an ecological practice that offers arguably marginal benefits while demanding such high costs in both labour and funding (Kimball et al., 2015) initially and indefinitely.

Reconciliation

Having discussed how Reservation and Restoration place pressure on economies, the final section of this article addresses Reconciliation as a plausible means of achieving a balance between humans and nature. Although costly to convert or establish, Reconciliation offers high monetary return potential. There are countless instances of Hotels in exotic places, such as the Red Sea Star Restaurant (sadly, now closed) in Eilat (Rosenzweig, 2003) and Heron Island, off the coast of Queensland, Australia (see Figure 3). The Heron Island Resort takes advantage of the annual turtle hatching event as a drawcard for tourism, while The Heron Island Research Station actively manages and studies the health of the reef and island ecosystem.

Not only does Reconciliation provide monetary gain for humans, but also a foothold for opportunistic species to disperse and thrive. For example, the man-made canals dug for the Turkey Point power station in Miami provided ideal habitat for crocodiles (Gaby, 1985), and agroforestry initiatives encourage a symbiotic relationship between our crops and native wildlife (Bagwhat et al., 2008). The coffee-based agroforest in Central America yielded less species richness than natural forest but far exceed numbers than traditional agricultural land use systems (Correia et al., 2010). Reconciliation is not an ‘offset’ system whereby economic theory legitimises habitat destruction (Spash, 2015) in an exchange for alternative environmental support (e.g. Carbon offsets – planting trees in exchange for fossil fuel consumption). It is a rational, plausible alternative to the separational view of humankind versus the environment.

Figure 3. Heron Island Resort & Research Station. Sustainable tourism guided by on-site researchers monitoring reef health and biodiversity (Robins, 2018).

Summary

As “soaring human demands collide with the earth’s natural limits” (Brown, 2002, p.25), environmental degradation becomes an ever increasing issue as human populations grow.

Reservation ecology, while comparatively cheap, sets aside land that no longer provides a useful resource to humans, works against the natural development of an ecosystem through exposure to existing pressures and acquiring adaptations to them (Marris, 2011; Shapiro, 2013). It also operates under the incorrect assumption that nature performs best in large isolated clumps (Fahrig, 2017). Reserves as a ‘natural time capsule’ are evolutionarily counterproductive, wasteful, and unsustainable.

Indeed, the same can be applied to Restoration that incurs immense capital investment and ongoing expenses in maintaining an unnaturally static environment dependant on biased baselines from the outset (Bjorkman & Vellend, 2010). Conversely, Reconciliation is a persuasive possibility that can engage industry leaders and market participants. It has the potential to guide us toward sustainable industry through opportunities such as agroforestry and ecotourism. The bigger question then becomes how to change people’s perception of biodiversity, and to alter policies and practices to reflect this eco-anthropic ideal.

Bibliography:

Balmford, A., Bruner, A., Cooper, P., Costanza, R., Farber, S., Green, R. E., … & Munro, K. (2002). Economic reasons for conserving wild nature. science, 297(5583), 950-953.

Bhagwat, S. A., Willis, K. J., Birks, H. J. B., & Whittaker, R. J. (2008). Agroforestry: a refuge for tropical biodiversity?. Trends in ecology & evolution, 23(5), 261-267.

Bjorkman, A. D., & Vellend, M. (2010). Defining historical baselines for conservation: ecological changes since European settlement on Vancouver Island, Canada. Conservation Biology, 24(6), 1559-1568.

Brown, L. (2002). Eco-economy. Editori Riuniti, Roma.

Colston, A. (2003). Beyond preservation: the challenge of ecological restoration. Decolonizing nature: strategies for conservation in a post-colonial era. Earthscan, London, 247-267.

Correia, M., Diabaté, M., Beavogui, P., Guilavogui, K., Lamanda, N., & De Foresta, H. (2010). Conserving forest tree diversity in Guinée Forestière (Guinea, West Africa): the role of coffee-based agroforests. Biodiversity and conservation, 19(6), 1725-1747.

Fahrig, L. (2017). Ecological responses to habitat fragmentation per se. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 48, 1-23.

Gaby, R., McMahon, M. P., Mazzotti, F. J., Gillies, W. N., & Wilcox, J. R. (1985). Ecology of a population of Crocodylus acutus at a power plant site in Florida. Journal of Herpetology, 189-198.

Kimball, S., Lulow, M., Sorenson, Q., Balazs, K., Fang, Y. C., Davis, S. J., … & Huxman, T. E. (2015). Cost‐effective ecological restoration. Restoration Ecology, 23(6), 800-810.

Lindenmayer, D., & Burgman, M. (2005). Practical conservation biology. Csiro Publishing.

Marris, E. (2011) Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World. Bloomsbury, USA.

Miller, B., Soulé, M. E., & Terborgh, J. (2014). ‘New conservation’ or surrender to development? Animal Conservation, 17(6), 509-515.

Rosenzweig, M. L. (2003). Win-win ecology: how the earth’s species can survive in the midst of human enterprise. Oxford University Press on Demand.

Shapiro, A. (2013). The Quarterly Review of Biology, 88(1), 45-45. doi:10.1086/669328

Spash, C. L. (2015). Bulldozing biodiversity: The economics of offsets and trading-in Nature. Biological Conservation, 192, 541-551.

Thomas, C. (2017) Inheritors of the Earth: How Nature Is Thriving in an Age of Extinction. Public Affairs, New York.

Thomas, C. D. (2011). Translocation of species, climate change, and the end of trying to recreate past ecological communities. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 26(5), 216-221.

Verdone, M. (2015). A cost-benefit framework for analyzing forest landscape restoration decisions. IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), Gland, Switzerland.tzerland.

Images:

Robins, J. (2018). Heron Island Resort & Research Station. Retrieved March 21, 2019, from heronisland.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Aerial_Heron-Island_Jordan-Robins_2.jpg.

Fotalia. (n.d.). Plant Growing Step on Money Stack Concept. Retrieved March 21, 2019, from https://www.crystalgraphicsimages.com/view/cg2p80086370c/plant-growing-step-on-money-stack-concept-finance-and-image.

Trap–Neuter–Return: Undermining New Zealand Conservation.

Posted: May 1, 2017 Filed under: 2017, ERES525 | Tags: Cats, conservation, nature, new zealand. 1 Comment

Trap Neuter Return logo. (Retrieved from http://www.ccfaw.org/TNR.html on 1/5/17)

Author: Olivia Carson

In New Zealand, conservation is a crucial tool used to maintain our unique ecosystem. But are our beloved feline friends undoing conservation’s hard work? Cats enjoy preying on some of New Zealand’s endemic species, such as birds like the kiwi, kererū and tui, reptiles like skinks, geckos and tuatara or invertebrates like weta. Statistics show that cats are having an impact on our native fauna, so is it time to revise programs which enable this behaviour to continue?

Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) is a management technique used in New Zealand (NZ) by participating SPCA clinics whereby wild free-roaming cats, of all ages, are being humanely captured, spayed, and health checked. Upon completion, they are returned to their original habitat where their presence is approved, or they are put up for adoption if they are seen fit for domestication (Levy, et al., 2013). Former SPCA National President, Bob Kerridge, and the majority of NZ’s SPCAs support TNR as it aids in the welfare of, “sick, injured, lost, abused or simply abandoned cats” and it leads to an eventual decrease in the wild cat population (Auckland SPCA, 2016). However, this support is rivalled with opposition from The Department of Conservation (DOC) and conservation minister, Maggie Barry, who in 2015 called for the SPCA to stop the programme altogether, claiming it was destructive to native birds (Smith, 2015). Throughout this article the positive and negative implications of TNR will be explored, arguing that from a conservationist’s perspective, this program, along with feral and stray cats need to go.

Cats are categorised by their behavioural differences, whether they are domestic, stray or feral. Domestic cats are those who live with an owner and depend on humans for their care and welfare. A stray cat is one who was once a domesticated animal but has become lost or abandoned and has their needs indirectly supplied to them by humans or their environment. Feral cats are born and raised in the wild and have few of their needs provided by people and tend to live away from centres of human habitation (Farnworth, et al., 2010). One behaviour which these cats share is their instinct to kill, with studies nationwide showing that many of NZ’s endangered species have targets on their backs.

A stray cat trapped in a TNR cage being released after neutering. (Retrieved from http://iowahumanealliance.org/trapneuterrelease on 1/5/17)

The debate on whether cats should be classified as pests is strongly controversial. 48% of households in NZ accommodate at least one cat, showing that us Kiwis have a real love for these furry creatures (Mckay, et al., 2009). DOC, on the other hand, consider cats as pests, due to their negative impacts on our native species (Abbott, 2008). This begs the question, why are programmes such as TNR supporting the release of these homeless and undomesticated cats back into the wild?

There are many reasons to support the use of TNR. In Rome, Italy, a study on a long-term TNR programme showed that cat colonies decreased by up to 24% over a 6-year period, demonstrating that loss of reproductive ability has a marked effect on the reduction of the number of unwanted kittens (Natoli, et al., 2006). Furthermore, by returning the cat to the environment after veterinary attention, it allowed them to continue using their hunting instincts towards decreasing mammalian pest populations. The same methodology can be applied to NZ as mammalian pests, such as mice and rats are also known to feast on New Zealand’s native species (Towns & Broome, 2003). Therefore, it could be reasoned that if cats were removed altogether from the ecosystem, it might experience a decline in native wildlife due to a rise in the rodent population.

The introduction of cats to NZ has seen some unfortunate outcomes for native species, which underwent evolution during a period where mammalian predators were non-existent (Norbury, et al., 2014). Domestic, stray and feral cats have all contributed to the extinction of 40% of NZ endemic birds (Sijbranda, et al., 2016). In 1894, a single cat was able to completely wipe out an entire species of Stephen’s Island Wren, who were thought to be taking refuge from mammalian pests on Stephen’s Island (Galbreath & Brown, 2004). This reinforces how destructive one cat, who may be from a TNR programme can be.

The stomach contents of one stray male cat in Ohakune, New Zealand. (Retrieved from http://www.doc.govt.nz/news/media-releases/2010/cat-nabbed-raiding-the-mothership/ on 1/5/17).

The average cat kills approximately 65 creatures a year (van Heezik, et al., 2010). Rats, one of NZ’s most devastating pests, arguably contribute just as much damage, along with ferrets, stoats, weasels and possums. Both government and territorial authorities use alternatives to TNR to control these predators which meet humane standards for example poison and traps. It could be debated that although a less favourable outcome for cats, instead of the SPCA spending money on neutering and providing medical attention, it could be considered more humane to euthanise. Recognising this will stop cats from having an unloved life on the street and ensures that no native animals will come to their demise in the future.

If TNR was terminated, then continued pest management would be essential. Instead of neutering and releasing trapped stray and feral cats, they would need to be humanely euthanised. Continued management would also benefit the eradication of the other pests which cats may prey on. New Zealand aims to have a pest-free ecosystem by 2050 and the Government, iwis, and regional councils are showing their support to this cause by providing approximately $70 million annually towards predator control (The Department of Conservation, 2014). This sum would continue to benefit pest management if TNR was stopped. There are humane pest control options which could be better advertised to the public (Goodnature and Victor professional traps), which may increase support, reinforcing that we don’t need cat input to sort our pest problem, just people’s support.

The negative consequences of having stray and feral cats in our environment far outweigh the positives. Most cat owners are reasonable people, agreeing that measures such as mandatory microchipping, registration and compulsory neutering, would allow for better care of future stray cats. If people complied with these rules, then stray cats could be returned to their owners. We don’t need to remove our much-loved pets altogether, but our native fauna needs protection too, the ones that define us as a nation, and for this to be achievable, TNR must go. TNR currently undermines conservation practices by allowing destructive animals to continue to roam freely. If it weren’t for cats “most-loved” status, it wouldn’t be an issue, as we don’t see rats being neutered and returned to the wild, do we?

References

Abbott, I. (2008). The spread of the cat (Felis catus) in Australia: Re-examination of the current conceptual model with additional information. Conservation Science Western Australia, 7, 1-17.

Auckland SPCA (2016). What We Do. Retrieved from Auckland SPCA: https://www.spcaauckland.org.nz/what-we-do/

Farnworth, M., Dye, N., & Keown, N. (2010). The legal status of cats in New Zealand: A perspective on the welfare of companion, stray and feral domestic cats (Felis catus). Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 13, 180-188.

Galbreath, R., & Brown, D. (2004). The tale of the lighthouse-keeper’s cat: Discovery and extinction of the Stephens Island wren (Traversia lyalli). The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc, 51, 193-200.

Levy, J., Gale, D., & Gale, L. (2013). Levy, J. K., Gale, D. W. Evaluation of the effect of a long-term trap-neuter-return and adoption program on a free-roaming cat population. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 222, 42–46.

Mckay, S., Farnworth, M., & Waran, N. (2009). Current attitudes toward, and incidence of, sterilization of cats and dogs by caregivers (owners) in Auckland, New Zealand. Journal of applied animal welfare science, 12, 331-344.

Natoli, E., Maragliano, L., Cariola, G., Faini, A., Bonanni, R., Cafazzo, S., & Fantini, C. (2006). Management of feral domestic cats in the urban environment of Rome (Italy). Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 77, 180-185.

Norbury, G., Hutcheon, A., Reardon, J., & Daigneault, A. (2014). Pest fencing or pest trapping: A bio-economic analysis of cost-effectiveness. Austral Ecology, 39, 795-807.

Sijbranda, D., Campbell, J., Gartrell, B., & Howe, L. (2016). Avian malaria in introduced, native and endemic New Zealand bird species in a mixed ecosystem. New Zealand Journal of Ecology,, 40(1), 72-79.

Smith, O. (2015). Express. Retrieved from Feral politics: New Zealand’s two-cat policy sparks FUR-ious row. http://www.express.co.uk/news/world/582420/New-Zealand-s-Prime-Minister-John-Key-two-cat-policy-controversy

The Department of Conservation. (2014). Predator Free 2050 [Brochure]. New Zealand. Retrieved from http://www.doc.govt.nz/Documents/our-work/predator-free-2050.pdf

Towns, D., & Broome, K. (2003). From small Maria to massive Campbell: Forty years of rat eradications from New Zealand islands. New Zealand Journal of Zoology, 30(4), 377-398.

van Heezik, Y., Smyth, A., Adams, A., & Gordon, J. (2010). Do domestic cats impose an unsustainable harvest on urban bird populations? Biological Conservation, 143(1), 121-130.

Is Yellowstone National Park a ‘pristine’ environment?

Posted: May 1, 2017 Filed under: 2017, ERES525 | Tags: environment, Management, national park, nature Leave a commentYellowstone National Park was created in 1872. It was the world’s first federally protected natural area. Located in Wyoming, the park spans 2.2 million acres and is known for its geothermal features, such as the Old Faithful geyser (NPS, 2017). There are over 400 species of animals including bears, bison and wolves, as well as over 1100 native plant species (Frank & McNaughton, 1992). Along with the wide range of diverse plant and animal species, Yellowstone has a long history of human habitation. If ‘pristine wilderness’ is defined as remaining in a pure state without human alteration (YourDictionary, 2017), can Yellowstone be considered pristine?

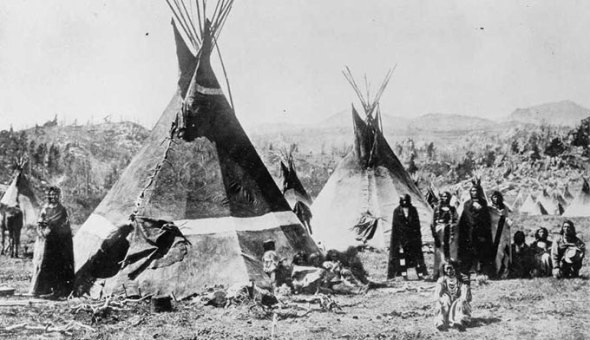

In 1870 when the nine members of the Washburn party embarked on the first official expedition of Yellowstone, they dismissed any signs of human habitation, describing it as primeval wilderness “never trodden by human footsteps” (Schullery & Whittlesey, 2003)(Spence, 1999). Sightings of Native Americans from the Shoshone, Blackfeet, Crow and Bannock tribes, were dismissed as they were considered “vanishing Indians” (Spence, 1999). Henry Washburn and Nathaniel Langford, leaders of the party, officially declared the area to be pristine wilderness (Spence, 1999).

Yellowstone clearly wasn’t untouched by humans, even before it was declared a national park. Rather, it was an area that had been moulded by thousands of years of human habitation and use (Spence, 1999). Evidence of this dates back to over 11,000 years ago when Paleo-Indian groups moved into the area at the end of the last ice age (Spence, 1999). Small bands of hunter/gatherers made use of the area leaving behind evidence of potsherds and obsidian quarries. These groups also altered their environment utilising controlled burns to maintain plant and animal habitats for agricultural purposes (Spence, 1999).

Figure 1: A Shoshone Tribe encampment in what was to become Yellowstone National Park, 1870.

The idea of pristine wilderness preceded the creation of Yellowstone. The ‘myth of wilderness’ is a cultural creation that came about through the romanticism of nature. The roots of this idea can be traced back to the writings of John Muir (Friskics, 2008). He described wilderness as a sacred space, ingraining upon the American mind the superiority of pristine wilderness rather than the coexistence between humans and nature (Marris, 2011). This seeming superiority of pristine wilderness was such a powerful idea that evidence of human habitation was often ignored.

Another philosophy, known as Cartesian dualism, was also serving to separate humans from nature during that period. Cartesian dualism is a western view that deemed nature as inferior along with indigenous people who remained entwined with it and its existence was for human consumption and control (Haila, 2000). Thus, to conserve naturally pure areas it was thought that humans needed to be removed from nature, resulting in the eviction of all four native tribes inhabiting Yellowstone in 1879.

The majority of scientists today would likely claim that national parks are not historically pristine. Humans are so deeply involved in the management and visitation of these sites. In 2012, 3.4 million people visited Yellowstone (NPS, 2017). Ecosystems within the park are managed, monitored and even altered. For instance, the Grey Wolf was hunted to extinction through a predator control program in 1926, only to bring it back by way of reintroduction in 1995 (Smith et al, 2003).

Yellowstone exists as a “public park … for the benefit and enjoyment of people”; it does not exist to be safeguarded from them.

Figure 2: Some of the over three million tourists to visit Yellowstone, 2015

There are very few landscapes that could still be considered pristine; perhaps none. Those that haven’t been altered directly by humans are now being affected by anthropogenic climate change.

We must rethink what pristine means at an environmental level.

A present day pristine environment could now be considered a “functioning ecosystem, largely intact and minimized human impacts” (Cronon, 1996). Many areas have been disturbed only to recover later. These areas display no obvious signs of human impacts; perhaps these are as pristine as it gets. These places contain plant and animal species that would be there in the absence of habitat loss, hunting, invasive species and other human-driven threats (Cronon, 1996).

Yellowstone, like all other national parks can’t be considered a pristine environment even by today’s definitions. Given the long history of human habitation, continued management, and the maintenance of the park for human enjoyment, it is anything but untouched. However, this doesn’t mean that it should be valued any less than actual pristine environments. If only truly pristine environments are worth protecting, we would have nothing left. Yellowstone contains a high diversity and density of our plants and animals worldwide (Waller (edt), 2012). Non-pristine environments like parks are often more accessible and are therefore the ones that humans will interact with and value greater. Gaining appreciation for nature whether it be pristine or not and if we are part of it or not will motivate future generations to protect it.

Kate Hunt

Works Cited

National Park Service (NPS), (2017). Modern Management. Retrieved March 22, 2017, from National Park Service Yellowstone: https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/historyculture/modernmanagement.htm

Cronon, W. (1996). The trouble with Wilderness: Or, getting back to the wrong wilderness. Environmental History, 1(1), 7-28.

Frank, D. A. (1992). The Ecology of Plants, Large Mammalian Herbivores, and Drought in Yellowstone National Park. Ecology, 73(6), 2043-2058.

Friskics, S. (2008). The Twofold Myth of Pristine Wilderness: Misreading the Wilderness Act in Terms of Purity . Environmental Ethics, 381-399.

Haila, Y. (2000). Beyond the Nature-Culture Dualism. Biology and Philosophy, 15(2), 155-175.

Marris, E. (2011). The Yellowstone Model. In E. Marris, Rambunctious Garden (pp. 17-37). New York: Bloomsbury.

National Park Service (NPS). (2016). Guidance for Protecting Yellowstone. Retrieved March 20, 2017, from Yellowstone: https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/management/protecting-yellowstone.htm

Schullery, P. &. (2003). Myth and History in the Creation of Yellowstone National Park. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press .

Smith, D. W. (2003). Yellowstone after Wolves . BioScience, 53(4), 330-340.

Spence, M. (1999). Before the Wilderness: Native Peoples and Yellowstone. In M. Spence, Dispossessing the wilderness: Indian removal and the making of the national parks (pp. 41-54). New York: Oxford Press.

Spence, M. D. (2000). Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks. In M. Spence, Dispossessing the wilderness . New York: Oxford Press.

Waller, J. (edt). (2012). Yellowstone Science. Wyoming: Yellowstone Association.

YourDictionary. (2017). Dictionary Definitions Pristine. Retrieved 2017, from Your Dictionary: http://www.yourdictionary.com/pristine

Figure 1: Retrieved 29th April 2017, from: http://www.yellowstonepark.com/yellowstone-sheepeater-tribe-ledgend/.

Figure 2: Retrieved 29th April 2017, from: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/travel/travel_news/article-2991863/Shocking-photos-reveal-destruction-Yellowstone-National-Park-hot-spring-tourists-throwing-coins-luck.html.

Transboundary Protected Areas: Making Peace With Nature – Melanie C. Berger

Posted: April 6, 2014 Filed under: 2014, BIOL420, Research Essay | Tags: conservation, ecology, nature, peace, peace parks, protected areas, transboundary, transfrontier, world parks 3 Comments“[We must] think beyond our boundaries, beyond ethnic and religious grounds and beyond nations in our global quest for a just world that values and conserves nature.”

– HM Queen Noor of Jordan, opening address at the Vth World Parks Congress, Durban, September 2003

Transboundary Protected Areas (TBPAs), emerging tools for conservation management, hold great potential for the protection and maintenance of biological diversity on the global scale. Originally classified as areas of protected land that cross over a national boundary, the definition of TBPAs has since been expanded to include:

- two or more contiguous protected areas across a national boundary;

- a cluster of protected areas and the intervening land;

- a cluster of separated protected areas without intervening land;

- a transborder area including proposed protected areas; and

- a protected area in one country aided by sympathetic land use over the border

(United Nations Environment Programme)

These cross-boundary protected areas are usually expansive, which can be essential for increasing landscape connectivity and restoring natural habitats. They also allow for greater control over border-specific conservation issues, such as invasive species, illegal trade and poaching, and the reestablishment of large species (UNEP-WCMC).

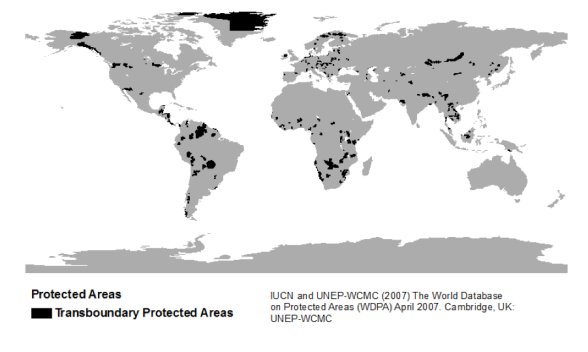

The concept of TBPAs has gained in popularity over recent years. The number of TBPAs has increased significantly from 59 in 1988 to over 200 in 2007 (Schoon, n.d.). Although the number of TBPAs has improved, our understanding of their success in conserving biodiversity has not. There is a gap in our knowledge, because there is a lack of studies dedicated to monitoring the success of these cross-boundary conservation efforts (Sandwith et al. 2005).How is it that the conservation success of an internationally recognized management tool has been so under-studied?

There were an estimated 227 Transboundary Protected Areas worldwide in 2007. (Schoon, n.d.)

The Nature of Peace

The very first TBPA was signed into existence in 1924 by Poland and Czechoslovakia under the Krakow Protocol, which “pioneered the concept of international cooperation in establishing border parks.” These protected areas were regarded as a way to reconnect and protect a natural landscape that happened to be divided by an international border, and although international cooperation was vital to their success, the theory of “fostering peace through nature” was not specified as a goal of their formation (Schoon, n.d.). However, over time, the prospect of fostering peace between conflicting nations began to emerge as a key motive for the creation of TBPAs. In 1932, the Glacier-Waterton International Peace Park was established in North America as the first officially declared international peace park. The peace park was dedicated to formally “commemorate the bonds of peace and friendship” between the United States and Canada. The London Convention Relative to the Preservation of Fauna and Flora in their Natural State was signed the following year, which boosted interest in transboundary conservation and called for cross-border cooperation when founding protected areas near political and physical borders (Chester, 2006). Many TBPAs were established in the following years, including the de facto transboundary parks that arose from African national parks following the independence and separation of Rwanda and Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire)(Mittermeier et al. 2005).

The array of economic and socio-political benefits that were achieved through cross-boundary cooperation quickly became clear. The term Parks for Peace (or peace parks) started to be used almost interchangeably with Transboundary Protected Areas, and many TBPAs began to be designed to promote goodwill and peace across international boundaries through the conservation of nature (Chester, 2006). There are numerous reports and studies on the socio-political and economic success of cross-boundary partnerships, which is likely to be the reason for their recent popularity (Ali, 2011, & Mittermeier et al. 2005).

Getting Back to Nature

There are two major explanations for why TBPAs are expected to be effective tools for large-scale conservation. First, the commonly large size of TBPAs allows for landscape connectivity across areas that would otherwise be separated by political, social and/or physical boundaries. This connection allows for the uninhibited movement of flora, fauna and ecological processes through the natural landscape (Chassot, n.d.). This can improve the integration of previously separated populations, enable increases in migration, and allow for range adjustment in response to climate change (McCallum et al. n.d.). On a landscape scale, it can also minimize the effects of land use and restore natural habitats. Second, basing management efforts on natural delineations instead of political ones can result in conservation-focused strategies that are more comprehensive and holistic. By pooling the physical, monetary and intellectual resources of two or more countries, the management practices can become more efficient. This can also minimize the impact of border-specific issues, such as invasive species, poaching, and smuggling (McCallum et al. n.d.).