Co-governance of Marine Reserves: A New Zealand Case Study:

Posted: May 18, 2019 Filed under: 2019, conservation, ERES525, Module Critique Assignment, Uncategorized | Tags: co-management, conflict, conservation, Governance, Marine Leave a commentPenny Ixer

Abstract:

Co-governance may enable the acknowledgment of Maori cultural values and practices when implementing marine reserves. In New Zealand, marine reserves represent only 0.3% of terrestrial waters. Governments associated with conservation are interested in the role marine reserves can play in restoring and protecting marine ecosystems. In this article, the conflicts of Māori traditions with marine reserves are described. Marine reserves were found to be unacceptable to many Māori, as customary access rights were eliminated. The article identifies co-governance as a potential solution to the conflict. Co-governance is the joint authority of common resources by governmental organisations, indigenous groups and local communities. Cultural co-management may allow equity in managing a protected systems, incorporating indigenous values, beliefs and rights into conservation practices. The case study of the Mimiwhangata marine reserve demonstrates how co-governance involves not only the management of resources, but also the management of relationships. Through the New Zealand case study, legislation involving co-governance of marine systems in New Zealand was found to be lacking. Legislation regarding governance of marine reserves in New Zealand requires modification to resolve the conflict between Māori culture and marine reserves.

Introduction:

Highly protected terrestrial reserves encompass approximately 30% of New Zealand’s land area (Langlois & Ballantine, 2005). No-take marine reserves however cover less than 0.3% of New Zealand’s terrestrial waters (Eddy, 2014). Figure 1 displays the disparity between New Zealand’s terrestrial and marine reserves.

Figure 1: The left figure shows the no-take terrestrial reserves on New Zealand’s main islands. The right figure displays New Zealand’s no-take marine protected areas. Reserves are shaded grey and drawn to scale. The reserve total area is shown to scale as circles. Figure credit: Langlois & Ballantine, 2005.

Marine reserves allow the conservation of marine ecosystems. Over-exploitation of marine resources have altered population structures, trophic relationships and ecosystem functioning (Langlois & Ballantine, 2005). No-take marine reserves aim to minimize human disturbances, creating conditions that allow recovery from over-exploitation. This module will establish how the implementation of marine reserves, is dependent upon balancing or striking a compromise between a range of people from different backgrounds and cultures, with a diversity of beliefs and values.

Marine Reserves Threaten Indigenous Rights:

The establishment of marine reserves in New Zealand is greeted by enthusiasm and objections. On average, the New Zealand public believe that 36% of New Zealand’s marine environment should be protected by no-take reserves (Eddy, 2014). A no-take marine reserve is the highest form of protection for marine ecosystems however has implications for many iwi, preventing traditional Māori practices and eliminating customary rights to gather resources from the sea (Dodson, 2014). Hence multiple iwi have opposed the formation of marine reserves. A Māori fisherman opposing the Department of Conservation’s (DOC) proposed no-take marine reserve in his local area, suggested his reservations were due to the restrictions placed on his traditional cultural practices (McCormack, 2010).

However, Māori culture also holds the traditional belief that the mauri (life-force) of marine systems should be protected for human prosperity (Costello, 2016). Marine reserves if governed with consideration to Maori rights and beliefs will allow kaitiakitanga (guardianship) to be restored. A major obstacle to the implementation of marine reserves lies in the governance of these systems.

Co-governance and Cultural Co-management:

Co-governance:

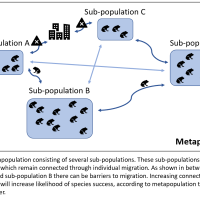

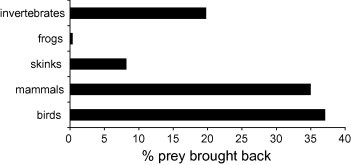

The formation of marine reserves can be challenging. Gaining support from local communities, iwi, commercial and recreational fisheries, and governmental organisations can become a long and disputed process (McCormack, 2010). Co-governance may allow a compromise to be formed between different groups and their values, sharing the authority of ecological systems, as shown by figure 2. Co-governance involves not only the management of resources, but also the management of relationships (Berkes, 2009). Common resources, such as marine ecosystems may benefit from co-governance, as co-management is strongly associated with adaptive management (Berkes, 2009).

Figure 2: Co-governance allows multiple groups, such as governmental organisations, indigenous groups and local communities to contribute their knowledge and values into managing a common resource. Co-governance of marine reserves will reduce conflict and increase societal benefits, for example restoring kaitiakitanga for marine ecosystems. Ecosystems will also benefit through the creation of the marine reserve and people’s conformation to the reserves’ no-take policy. Figure credit: Penny Ixer.

Cultural Co-management:

Cultural co-management involves the shared management of resources held in common (not privately owned) between cultural groups, governments and local communities (Carlsson & Berkes, 2005). Cultural co-management of protected ecosystems is built on the foundation that people whose livelihoods are affected by management decisions, have the right to share in those decisions. Cultural co-management promises to reduce conflict and incorporate indigenous values, beliefs and knowledge into conservation (Pinel & Pecos, 2012).

Cultural co-management involving the state and the Miriuwung-Gajerrrong people of Western Australia, demonstrates how cultural co-management can provide equity in managing a protected area (Hill, 2011). Cultural co-management established a balance between indigenous values, and state conservation values. Unfortunately, cultural co-management has also been associated with the continued marginalization of indigenous communities, as governmental agencies retain principal authority (Hill, 2011; Pinel & Pecos, 2012). Nevertheless, cultural co-management may enhance the equity, empowerment and compliance of indigenous communities when managing New Zealand marine reserves.

Mimiwhangata Marine Reserve:

The potential establishment of a marine reserve in Mimiwhangata, New Zealand was characterised by co-governance. Concerned by the degradation of Mimiwhangata’s marine ecosystem, DOC and the local Māori iwi, Te Uro o Hikihiki sought to establish and co-govern a marine reserve (refer to Fig. 3) (Dodson, 2014). Represented by a leadership group, Te Uri o Hikihiki believed co-governance of the marine reserve would advance their empowerment, restore kaitiakitanga and increase rangatiratanga (self-determination) (Dodson, 2014). Te Uri o Hikihiki and DOC recognised by reinstating traditional authority with co-governance, the iwi’s resulting empowerment would lead to successful conservation outcomes.

Figure 3: The proposed Mimiwhangata marine reserve boundary options proposed and debated by Te Uri o Hikihiki, DOC, Te Whanau Whero and local community groups. Despite much support, the proposed marine reserve was not established due to inequity in co-governance authority. Figure Credit: Dodson, 2014.

Whilst DOC and Te Uri o Hikihiki supported the establishment of the proposed marine reserve, Te Whanau Whero a nearby iwi did not (Dodson, 2014). Te Whanau Whero perceived the marine reserve to restrict their rights, mana whenua (customary authority), and traditional practices (Dodson, 2014). Co-governing marine reserves establishes an opportunity for marine conservation which doesn’t detriment Māori traditions. Unequitable authority allocated to DOC however may further marginalize indigenous rights.

There are several problems within New Zealand legislation, regarding indigenous rights to authority of marine reserves. The 1998 Customary Fishery Regulations allows iwi to establish marine reserves (McCormack, 2010). Application of these marine reserves however is dependent approval from other interested parties. Current co-governance legislation means the Crown acting through DOC have the final say regarding marine reserve management (Dodson, 2014). The cross-cultural partnership between Te Uri o Hikihiki and DOC aimed to empower local iwi, however the restricted co-governance framework under current legislation was unacceptable to the level of preventing unified local support for the Mimiwhangata marine reserve (Dodson, 2014). If co-governance provides equal authority between cultural groups and governmental organisations, multiple actors beliefs, values and knowledge will be recognized. Co-governance will potentially minimize marginalization of indigenous communities and increase successful marine reserve implementation.

Conclusion:

Marine reserves provide an important tool to conserving marine ecosystems. The successful establishment of marine reserves however depends on balancing all actors’ values, beliefs and practices. Throughout history, Māori claims to the sea have been in conflict with the New Zealand government. Many Māori may be limited by marine reserves, as they restrict iwis’ connection to marine ecosystems. Co-governance will allow the joint management of resources, potentially increasing the equity, empowerment and compliance of interested parties. Legislation in New Zealand however is incapable at enabling co-governance of marine reserves. This subsequently disempowers Māori rights to common property and reduces the number of marine reserves implemented. When implementing cultural co-governance of marine reserves, authority should be equally distributed between cultural groups, governmental organisations and local communities, to prevent marginalization of indigenous communities and conservation failure. Legislation regarding governance of marine reserves in New Zealand will need modification to appropriately enable co-management of marine reserves.

References:

Ballantine, B. (2014). Fifty years on: Lessons from marine reserves in New Zealand and principles for a worldwide network. Biological Conservation, 176, 297-307.

Banks, S. A., & Skilleter, G. A. (2010). Implementing marine reserve networks: A comparison of approaches in New South Wales (Australia) and New Zealand. Marine Policy, 34(2), 197-207.

Berkes, F. (2009). Evolution of co-management: Role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. Journal of Environmental Management, 90(5), 1692–1702.

Carlsson, L., and F. Berkes. 2005. Co-management: Concepts and methodological implications. Journal of Environmental Management, 75(1), 65-76.

Costello, M. J. (2016). Sustainable fisheries need reserves. Nature, 540, 341.

Dodson, G. (2014). Co-Governance and Local Empowerment? Conservation Partnership Frameworks and Marine Protection at Mimiwhangata, New Zealand. Society & Natural Resources, 27(5), 1-19.

Eddy, T. D. (2014). One hundred-fold difference between perceived and actual levels of marine protection in New Zealand. Marine Policy, 46, 61-67.

Hill, R. (2011). Towards equity in indigenous co-management of protected areas: cultural planning by Miriuwung-Gajerrong People in the Kimberley, Western Australia. Geographical Research, 49(1), 72-85.

Langlois, T. J., & Ballantine, W. J. (2005). Marine ecological research in New Zealand: Developing predictive models through the study of no-take marine reserves. Conservation Biology, 19(8), 1763-1770.

McCormack, F. (2010). Fish is my daily bread: Owning and transacting in Māori fisheries, Anthropological Forum, 20(1), 19-39.

McCormack, F. (2012). Indigeneity as process: Māori claims and neoliberalism. Social Identities, 18(4), 417-434.

Pinel, S. L., & Pecos, J. (2012). Generating co-management at Kasha Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument, New Mexico. Environmental Management, 49(3), 593, 604.

Willis, T. J., Millar, R. B., Babcock, R. C. (2003). Protection of exploited fish in temperate regions: High density and biomass of snapper Pagrus auratus (Sparidae) in northern New Zealand marine reserves. Journal of Applied Ecology, 40(2), 214-227.

Conflict within New Zealand Conservation Strategy: Cat owners vs Conservation

Posted: May 16, 2019 Filed under: 2019, conservation, ERES525, Module Critique Assignment, Uncategorized | Tags: Cats, conflict, conservation, environment, new zealand. Leave a commentBy Henrietta Ansell

Photograph: Vasiliy Vishnevskiy/Alamy

Abstract

Protecting New Zealand’s unique native wildlife is of substantial importance to its people. To support biodiversity, national strategies have been put in place in order to eradicate invasive predators. However, cats, being feral, stray or household pet have slipped through the cracks. Companion cats are responsible for 18-44 million prey items a year. These prolific hunters must be managed in order to conserve native biodiversity within NZ. Due to cat owner’s strong connection with their pets, conflict has arisen. In order to make fair management plans, there needs to be further investigation into the aftereffects of cat reduction. In addition, it is imperative the cat owner values are incorporated into conversation prior to the implementation of management plans.

Introduction

New Zealand’s unique island flora and fauna is of substantial importance to its people. Many species are considered taonga, with high cultural value and identity (Holzapfel et al., 2008). NZ’s struggle to protect biodiversity is due to endemic species evolving in absence of mammalian predators (Dowding & Murphy, 2001). Due to this, native fauna lack defensive adaptations and as a result, invasive predators have devastated native fauna populations (Dowding & Murphy, 2001).

Conservation campaigns such as Predator Free 2050 are looking to alleviate the pressure of invasive mammals on NZ Fauna. Their focus is limited to stoats (Mustela erminea), brushtail possums (Trichosurus vulpecula), and rats (Rattus rattus, Rattus norvegicus, Rattus exulans) (Owens, 2017), leaving remaining mammalian predators unaccounted.

Cats. Feral, stray or household pet, these furry beasts are having a detrimental effect on NZ’s wildlife (Morgan et al., 2009). Cats (Felis catus) have been a beloved companion animal since their domestication. Around 35-44% of NZrs own one or more cats in their home, considering them one of the family (Walker et al., 2017).

The management of cats has been controversial in NZ for a while. Conflict has arisen between conservationist and the public over the strict management or possible eradication of cats (Walker et al., 2017). Due to the value humans place on cats, complete eradication would be unjustified. In order to implement fair and effective management plans, extensive research into the consequences of cat restrictions must be conducted. In addition, the pet owner values must be incorporated into management plans in order to be successful.

What threat are cats posing to NZ Biodiversity?

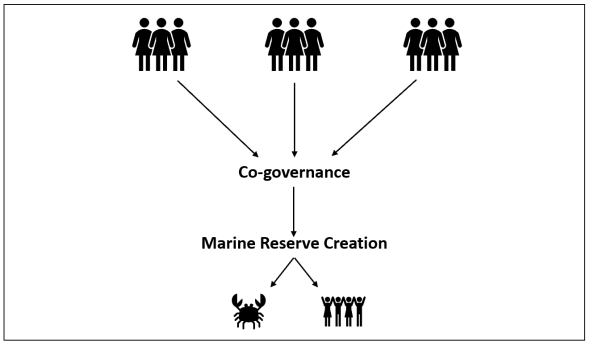

Cats are known to have detrimental effects on vulnerable species (Nogales et al., 2013). A majority of literature is based on the effects of feral cat populations and their negative impacts on wildlife. However, companion cats are also detrimental to native fauna in urban areas (Walker et al., 2017). Household cats are responsible for 18-44 million prey items a year (Walker et al., 2017). Yolanda van Heezik et al. (2010) found birds are cat’s priority prey (fig1), with 45% of birds being native. However, cats are opportunistic, generalist hunters and will target anything available (Willson et al., 2015; Walker et al., 2017).

Figure 1: Birds are shown to be priority prey (van Heezik et al., 2010).

Cat predation in urban areas act as a sink for birds (van Heezik et al., 2010). Prey populations are supplemented by surrounding landscapes and are being depleted by consistent cat predation (van Heezik et al., 2010). Cat populations in urban areas do not fluctuate with prey population density, due to household cats being regularly fed by their owners (van Heezik et al., 2010). Resulting in the reduction of native bird populations from surrounding landscapes, as well as the prevention of a subsisting populations within urban areas. Cats on the edges of cities may predate into rural habitats, where native fauna reside (van Heezik, 2010; Morgan et al., 2009). Many of our native birds are threatened, such as Kiwi (Apteryx), which juveniles are found to be predated upon by cats (McLennan et al.,1996) Therefore, it is important that we lower predation as much as possible.

As cats also prey on other pests’ species such as rats, there is speculation that these lower level predators will increase in abundance if cats are eradicated. However, a study conducted by Parsons et al., (2018) found that rat abundance isn’t affected by cat presence. Although rat sightings are lower in the presence of cats, this is a result of rats altering behaviour in order to avoid predation. The study was completed in New York, USA, therefore results in NZ may differ. This calls for additional research into the areas of cat predation of other pests within NZ. Actively reducing cat populations without consideration of potential pest population booms may have devasting results on native fauna.

Conflict in Priorities

Cat ownership is deep-rooted within western society (van Heezik, 2010). Many people feel extremely close to their pets, even deeming them part of the family. Owning a pet comes with physical and psychological benefits to human wellbeing (Crawford et al., 2006). Frequently people will value their pets over conservation concerns.

New Zealanders aren’t shy to the idea of cat management. A survey of NZers found 78% support the National Cat Management Strategy regarding feral and stray cats, but the public aren’t as concerned with the management of companion cats (Walker et al., 2017). Before implementing strategy, it is imperative to gather information on public opinion (Linklater et al., 2019). Without doing so, campaigns can be met with hostility and conflict.

Values are profoundly embedded among different groups and often continue to be robust throughout generations, they may alter with time but will never be fully replaced (Manfredo et al., 2016). It is impossible to try and force a value change upon society, and if enforced conservation strategies will fail as a result (Manfredo et al., 2016). Therefore, it is important to find common ground and create conversation around conflict. In turn, within cat management, this allows pet owners values to be incorporated when policy change is implemented.

Conclusion

There is conflict surrounding cat management strategy due to a difference in values. We cannot ignore that our companion cats are influencing biodiversity in urban areas. In order to conserve native biodiversity, it is imperative that comprehensive research is completed to predict outcomes of feline management. In addition, it is important to incorporate public opinion and cat owner values within strategy. If not, management plans may not be adopted by general public and fail to create results.

In the meantime, what can you do?

Cat confinement

Confinement is not only effective for conservation but acts as protection for pets as well (Linklater et al., 2019). Keeping your cat indoors after dark will reduce night-time predation, however, 24hr hour cat confinement is deemed the most effective by conservationists (Linklater et al., 2019). Either way, confining your cat indoors will reduce predation on native fauna.

Cat accessories

The introduction of Birdsbesafe® cat collar, a quick release brightly covered sleeve (fig 2), has proven to reduce cat kill count from 300 to 39 per year (Willson et al., 2015). Cats also become accustom to Birdsbesafe® collars within 30 minutes 69% of the time. As a result, these collars will allow cats to be outside but also exhibit diminished predation.

Figure 2: Birdsbesafe® Cat Collar (Willson et al., 2015).

References

Crawford, E. K., Worsham, N. L., & Swinehart, E. R. (2006). Benefits derived from companion animals, and the use of the term “attachment”. Anthrozoös, 19(2), 98-112.

Dowding, J. E., & Murphy, E. C. (2001). The impact of predation by introduced mammals on endemic shorebirds in New Zealand: a conservation perspective. Biological Conservation, 99(1), 47-64.

Holzapfel, S., Robertson, H. A., McLennan, J. A., Sporle, W., Hackwell, K., & Impey, M. (2008). Kiwi (Apteryx spp.) recovery plan. Threatened species recovery plan, 60.

Linklater, W. L., Farnworth, M. J., van Heezik, Y., Stafford, K. J., & MacDonald, E. A. (2019). Prioritizing cat‐owner behaviors for a campaign to reduce wildlife depredation. Conservation Science and Practice, e29.

Manfredo, M. J., Bruskotter, J. T., Teel, T. L., Fulton, D., Schwartz, S. H., Arlinghaus, R., … & Sullivan, L. (2017). Why social values cannot be changed for the sake of conservation. Conservation Biology, 31(4), 772-780.

McLennan, J. A., Potter, M. A., Robertson, H. A., Wake, G. C., Colbourne, R., Dew, L., … & Reid, J. (1996). Role of predation in the decline of kiwi, Apteryx spp., in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 27-35

Metsers, E. M., Seddon, P. J., & van Heezik, Y. M. (2010). Cat-exclusion zones in rural and urban-fringe landscapes: how large would they have to be?. Wildlife Research, 37(1), 47-56.

Morgan, S. A., Hansen, C. M., Ross, J. G., Hickling, G. J., Ogilvie, S. C., & Paterson, A. M. (2009). Urban cat (Felis catus) movement and predation activity associated with a wetland reserve in New Zealand. Wildlife Research, 36(7), 574-580.

Nogales, M., Vidal, E., Medina, F. M., Bonnaud, E., Tershy, B. R., Campbell, K. J., & Zavaleta, E. S. (2013). Feral cats and biodiversity conservation: the urgent prioritization of island management. Bioscience, 63(10), 804-810.

Owens, B. R. I. A. N. (2017). The big cull. Nature, 541, 148-150.

Parsons, D., Michael, H., Banks, P. B., Deutsch, M. A., & Munshi-South, J. (2018). Temporal and space-use changes by rats in response to predation by feral cats in an urban ecosystem. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 6, 146.

van Heezik, Y. (2010). Pussyfooting around the issue of cat predation in urban areas. Oryx, 44(2), 153-154.

van Heezik, Y., Smyth, A., Adams, A., & Gordon, J. (2010). Do domestic cats impose an unsustainable harvest on urban bird populations?. Biological Conservation, 143(1), 121-130.

Walker, J., Bruce, S., & Dale, A. (2017). A survey of public opinion on cat (Felis catus) predation and the future direction of cat management in New Zealand. Animals, 7(7), 49.

Willson, S. K., Okunlola, I. A., & Novak, J. A. (2015). Birds be safe: can a novel cat collar reduce avian mortality by domestic cats (Felis catus)?. Global Ecology and Conservation, 3, 359-366.

Resolving conservation conflict: challenges and solutions

Posted: May 16, 2019 Filed under: 2017, 2019, Uncategorized | Tags: conflict, fisheries, Government, Marae Moana, NGO, purse seine fishing Leave a comment

By Alanna Smith

By Alanna Smith

Abstract

Conservation conflict is increasing across the globe and can result in destructive and costly events. A common characteristic driving this conflict is the lack of early stakeholder engagement resulting in a loss of trust between conflicting parties. Early stakeholder engagement ensures the values and goals of all relevant stakeholders are considered at the very beginning. All stakeholders need to be transparent in their communications to allow for well-informed discussions thus helping mitigate possible conservation conflicts. Here, I explore a case study from the Cook Islands in the Pacific to highlight the conservation challenges faced by both a local non-government organisation and a local government department. Further, I will discuss a range of mitigation strategies that could be applied to avoid conservation conflict.

Introduction

Conservation conflicts are increasing across the globe and can result in negative impacts on biodiversity, human livelihoods and human well-being (Redpath et al 2013). Conservation conflict is defined as situations where two or more parties with strong opinions clash over conservation objectives (Redpath et al 2013). This definition highlights that conservation conflicts occur primarily between people or groups who have opposing values and views, or when there is a lack of trust between stakeholders (Woodroffe et al 2005). Although conflicts can sometimes positively influence change (Wittmer et al 2006), they are more commonly destructive and costly. They not only threaten effective conservation but also prevent economic development, social equality and resource sustainability (Woodroffe 2005). Conservation conflicts arise because of poor consultation resulting in some key stakeholders being excluded from conservation planning (Katz 1998) or being disadvantaged in negotiations by not being fully aware of the available evidence (Armitage et al 2009).

Conflict in the Cook Islands

In the Cook Islands, a conflict over the lack of an environmental impact assessment (EIA), together with a lack of adequate public consultations around commercial fishing by purse seine vessels, ended up in the High Court in 2017 (Te Ipukarea Society 2019). The case against the Government was initiated by the local proactive Non-Government Organisation Te Ipukarea Society (TIS) joined by a group of Rarotonga’s traditional leaders from Te au o Tonga who challenged the government’s action on signing off on a fisheries partnership deal with the European Union in 2016. TIS raised awareness of the government’s activity to local media sources (TV, newspaper articles, social media), resulting in a public outcry, including three protest marches and a petition to ban purse seine fishing within the Cook Islands Exclusive Economic Zone. The case was lost, but on appeal, Te Ipukarea Society won based on the fact that the required EIA had not been conducted. The government is now mounting another appeal (CINEWS 2018).

Anti purse seine fishing protest marches was attended by a range of different community members from government workers, private sectors to concerned residents. Te Ipukarea Society 2019

Mitigating the Cook Islands Conflict

The Cook Island case study provides a clear example of poor early stakeholder engagement leading to conflict. Such a conflict could have been averted by ensuring each stakeholders goals and values were defined and recognized from the very beginning (Reed 2008). Early engagement would then have been strengthened by the availability of quality, transparent information being made available to all stakeholders, allowing for well-informed decision-making and the building of trust between stakeholders (Redpath et al 2012).

On top of building trust through early stakeholder engagement, it is essential that parties are willing to come to a negotiated agreement (Ramsbotham et al 2011). Parties who feel they have been misled or have opposing values might not consider negotiations, and might try harder to undermine a process (Satterfield 2002). An example of this occurred in the given case study where the government’s interest was based on economic gain, as opposed to a more conservation focus from the NGO’s perspective. Other examples of non-negotiating can occur when groups do not acknowledge the legitimacy of other parties (Thirgood & Redpath 2008), labelling them as trouble-makers of no real significance. It is difficult to achieve a win-win situation when negotiating amongst different stakeholders (Peterson et al 2005). This is why it is important that goals, arguments and potential trade-offs are made clear at the start, before seeking solutions (McShane et al 2011).

Protection through legislation

Legislation that is proactively enforced can work well to manage conservation conflict (Barunch- Mordo et al 2011). It is also true that much of the legislation created around conservation conflict can be ignored by one party, or deemed unfair (Young et al 2010). This was the case for the Cook Islands purse seine fishing case study when the government was unsuccessful in weakening regulations within the Marae Moana Act. Marae Moana is a multi-use marine protected area created in 2017, making Marae Moana the largest multiple-use marine protected area in the world at the time of it being passed (RNZ 2017). The Marae Moana Act states that “A marine protected area of 50 nautical miles (measured from each coastline of the 15 islands that makes up the Cook Islands) is established, all seabed minerals activities and large-scale commercial fishing in the area are prohibited” (Marae Moana Act 2017 section 3). Cook Islands government were pushing for a fisheries protected area of 24 nautical miles from each coastline, as this would have been more appealing to commercial fishing companies, but eventually, the Act was passed with no large-scale commercial fishing activity to occur within the proposed 50 nautical miles of each island (RNZ 2017). Having a legislated Act then reassured the Cook Islands people that government was then contracted by law to abide by the new legally binding regulations.

Marae Moana advocates Kevin Iro and Jacqueline Evans celebrate the passing of legislation which has made the entire Cook Islands Exclusive Economic Zone the largest multi-use marine reserve in the world. Cook Islands News 2017.

The Dichotomy of Evidence

Scientific information played a crucial role in justifying both the government’s and TIS’ position statements and calls for action in the Cook Island case study. Science plays a fundamental role in understanding the root causes of conflict, by assessing human-wildlife impacts and providing alternative mitigation techniques and exploring trade-offs (Redpath et al 2012). Scientists however can show a bias based on their position or work, hence the need for scientists to acknowledge their own values in order for stakeholders to make unbiased decisions (Sarewitz 2004). There is also the chance that science can become politicised, with stakeholders focusing solely on research that supports their position (Thirgood & Redpath 2005).

Careful consideration is also needed when considering messages portrayed in the media, which was regularly being used during the anti purse seine fishing campaign to promote various different opinion pieces and statistical information. Often the media tend to exaggerate conflict issues rather than state the facts based on real evidence (Barua 2010). Support for constructive journalism is therefore an important part of achieving effective conflict resolutions (Rejic 2004) as well as ensuring readers are aware of the author’s background and position.

Conclusion

The core principle to mitigating conservation conflict is building trust between all relevant stakeholders. This trust is built by involving key stakeholders from the start of discussions and negotiations. Transparency from the beginning between all stakeholders is key to recognising each party’s position, values and goals, as well as providing all available evidence that states any uncertainties or gaps. Transparency is crucial so that all stakeholders can participate in informed discussions when considering the available evidence. This allows for stakeholders to make logical trade-offs when negotiating a way forward. Conservation conflicts can result in unfortunate institutional clashes, particularly on a small island state such as the Cook Islands. That being said, its small population size also provides the opportunity for improved information-sharing and the coordination of early, well-represented stakeholder consultations and discussions to mitigate future conservation conflicts. The given solutions provide a way forward in terms of achieving positive, collaborative conservation change.

References

Ansell, C & Gash, A. 2008. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 18, 571

Armitage, D.A., Plummer, R., Berkes, F., Arthur, R.I., Charles, A.T., Davidson-Hunt, I.J.,

Diduck, A.P., Doubleday, N.C., Johnson, D.S., Marschke, M., McConney, P., Pinkerton, E.W., Wollenberg, E.K. 2009. Adaptive co-management for socioecology complexity. Front. Ecol. Environ. 7, 95-102

Baez, J.C., Fernandez-Torres, F., Alayon, P.J.P., Ramos, M.L., Deniz, S., Abascal, F. 2018. Updating the statistics of the EU-Span Purse Seine Fleet in the Indian Ocean (1990-2017). Research Gate.

Barua, M. 2010. Whose issue? Representations of human elephant conflict in Indian and international media. Sci. Commun., 32:55-75

Baruch-Mordo, S., Breck, S.W., Wilson, K.R., Broderick, J. 2011. The carrot or the stick? Evaliation of education and enforcement as management tools for human wildlife conflicts. PLoS ONE 6, e15681

Cook Islands News. 2017. Marae Moana becomes reality. Retrieved from http://www.cookislandsnews.com/item/65077-marae-moana-becomes-reality/65077-marae-moana-becomes-reality

CINEWS. 2018. Court win on purse seine claim. Retrieved from http://www.cookislandsnews.com/national/environment/item/70956-court-win-on-purse-seine-claim

Katz, C. 1998. Whose culture, whose nature? Private productions of space and the ‘preservation’ of nature. In Remaking Reality: Nature at the Millennium (Braun, B. and Castree, N., eds), pp. 46-63, Routledge

McShane, T.O., Hirsch, P.D., Trung, T.C., Songorwa, A.N., Kinzig, A., Monteferri, B.,

Mutekanga, D., Thang, H.V., Dammert, J.L., Pulgar-Vidal, M., Welch-Devine, M.,

Brosius, P., Coppolillo, P., O’Connor, S. 2011. Hard choices: Making trade offs between biodiversity conservation and human well-being. Biological Conservation. Vol 144: 3: 966-972

Peterson, M.N., Peterson, M.J., Peterson, T. R. 2005. Conservation and the myth of consensus. Conserv. Biol. 19: 762-767

Radio New Zealand. 2017. Cook Islands Marae Moana legislation passed. Retrieved from https://www.radionz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/335067/cook-islands-marae-moana-legislation-passed on 9th May 2019.

Ramsbotham, O., Miall, H., Woodhouse, T. 2011. Contemporary conflict resolution (3rd edn), Polity Press

Redpath, S.M., Young, J., Evely, A., Adams, W.M., Sutherland, W.J., Whitehouse, A., Amar, A., Lambert, R.A., Linnell, J.D.C., Watt, A., Gutierrez, R.J. 2013. Understanding and managing conservation conflicts. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. Vol. 28, No, 2.

Reed, M.S. 2008. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: a literature review. Biol. Conserv. 141: 2417-2431

Rejic, D. 2004. The news media and the transformation of ethnopolitical conflicts. The Berghof Handbook, Springer. Pp. 319-321

Sarewitz, D. 2004. How science makes environmental controversies worse. Environ. Sci. Policy, 7, 385-403

Satterfield, T. 2002. Anatomy of a conflict: Identity, Knowledge, and Emotion in Old-growth Forests. University of British Columbia Press.

Te Ipukarea Society. 2019. News. Retrieved from http://www.tiscookislands.org/news_page.php

The Marae Moana Act 2017.

Thirgood, S., Redpath, S. 2008. Hen harriers and red grouse: science, politics and human-wildlife conflict. J. Appl. Ecol., 45: 1550-1554

Wittmer, H., Rauschmayer, F., Klauer, B. 2006. How to select instruments for the resolution of environmental conflicts? Land Use Policy. Vol 23:1:1-9.

Woodroffe, R. 2005. People and Wildlife: Conflict or Coexistence?, Cambridge University Press

Woodroffe, R., Thirgood, S., Rabinowitz, A. 2005. The future of coexistence: resolving human-wildlife conflicts in a changing world., Cambridge University Press

Young, J.C., Marzano, M., White, R.M., McCracken, D.I., Redpath, S.M., Carss, D.N., Quine, C.P., Watt, A.D. 2010. The emergence of biodiversity conflicts from biodiversity impacts: characteristics and management strategies. Biodivers. Conserv. 19, 3973-3990