Te Urewera: Governance Shifts with Co-Management

Posted: May 16, 2019 Filed under: 2019, conservation, ecology, ERES525, Module Critique Assignment, Uncategorized | Tags: ecology, Governance, Management, new zealand., personhood Leave a commentby Liam McAuliffe

Definitions of terms included in glossary. These terms are italicized the first time they appear in body text.

Abstract

Te Urewera in the eastern North Island of New Zealand is an archetypal example of Maori alienation from their land through establishment of Crown wildlife reserves. In 2014, Te Urewera was afforded legal personhood complete with the rights and liabilities of a person. Previously a national park, the 2014 Te Urewera Act removed Crown vesting of the land and now the land is represented by a board of Tūhoe and Crown, effectively creating a co-management governance system. This novel system has the capacity to inform a new wave of conservation in New Zealand that will allow deeper involvement of iwi, whilst maintaining conservation goals. In this essay I will explore the history of Te Urewera, the Te Urewera Act and the critiques of co-management that need to be addressed to achieve these goals. If we are able to effectively address issues with these systems, Te Urewera could set a precedent of effective conservation nationwide.

Introduction

The shift towards co-management of Te Urewera is an unprecedented act globally, due to its foundation of the land as a legal person. In 2014, the land formally known as Te Urewera National Park was afforded environmental personhood, no longer vested with the Crown (Ruru, 2014; Te Urewera Act, 2014). As a result, the Te Urewera Board was established, comprised of Crown and Tūhoe members, to act on behalf of the land (Ruru, 2014; Te Urewera Act, 2014; Magallanes, 2015).

This Act shifted the Crown governance of Te Urewera to a co-management system with an emphasis on Tūhoetanga and conservation (Ruru, 2014; Te Urewera Act, 2014; Magallanes, 2015). This governance structure will be scrutinised in future years but has the capacity to change how our reserves are managed, promoting conservation and allowing larger involvement from Maori (Hill & McKay, 2018). If we can address critiques of co-management, we will gain a deeper pool of knowledge from which to carry out conservation. This important step forward would not only benefit New Zealand but create a precedent for the rest of the world to follow.

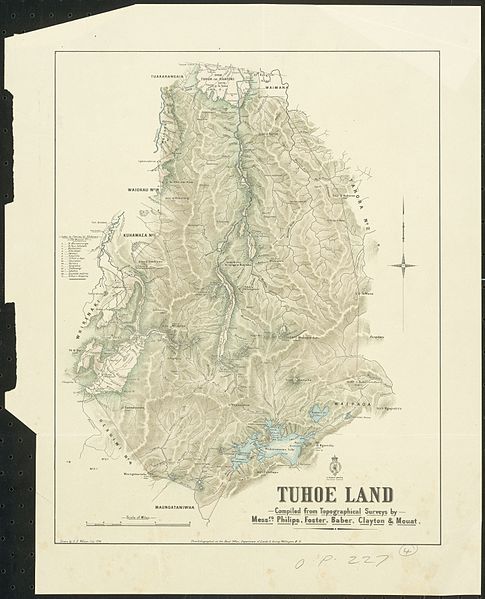

Map of Te Urewera, surveyed by European Colonials.

GP Wilson, 1896

History of Te Urewera

The land of Te Urewera has often been the cause of conflict. Tūhoe did not sign the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi and as a result, Tūhoe and Te Urewera were forcibly made subjects of the Crown (Magallanes, 2015). In 1954, Te Urewera was given National Park status without the consultation of Tūhoe, a process further alienating Tūhoe from the area and preventing them from engaging with cultural practices of mahinga kai (Arif, 2015; Magallanes, 2015; Hill & McKay, 2018).

There was eventually a call for co-operation between the Government and iwi, for Tūhoe land access to be restored and for a new governance structure of Te Urewera (Hill & McKay, 2018).

Te Urewera Act 2014

The 2014 Te Urewera Act addressed these issues in a way adhering to Tūhoe cultural identity through legal procedures. The primary intention of the act is to remove Crown vesting in the land for perpetuity and to afford the legal rights and liabilities of a person to Te Urewera (Ruru, 2014; Te Urewera Act, 2014; Dale & Petronelli, 2018).

As a result of being afforded environmental personhood, the Te Urewera Board was established to act on behalf of the land (Ruru, 2014; Te Urewera Act, 2014). The board is comprised of six Tūhoe members and three Crown members, elected by the Minister of Conservation, effectively forming a method of co-management of Te Urewera (Ruru, 2014; Te Urewera Act, 2014; Dale & Petronelli, 2018).

Actions taken by the board on Te Urewera must comply with the act’s stated goals; to strengthen Tūhoetanga, preserve Te Urewera ecosystems, species, biodiversity and beauty, and to maintain public engagement and recreation on the land (Te Urewera Act, 2014).

Te Urewera is unique globally as its affordance of environmental personhood has been the sole driver of the creation of a co-management system to act on behalf of the land. As such, the effectiveness of this system has yet to be seen and for Te Urewera to be successful we must first address some of the critique associated with co-management systems.

Addressing Critiques of Co-Managament

A fundamental issue with co-management structures is their inability to effectively incorporate both party’s values in the intended conservation (Nadasdy, 2005; Blaser, 2009).

Examples globally demonstrate how indigenous values and knowledges continue to take a back foot in co-management systems, despite the intention for a balance between the two parties (Nadasdy, 2005; Blaser, 2009). This is often demonstrated through the continuation of a western science methodology using traditional knowledge and practice as supplementary data rather than of equal value (Nadasdy, 2005; Blaser, 2009).

This criticism is of particular importance with the co-management of Te Urewera, as there can be dramatically different conservation values and practices between iwi and the Crown (Weaver, 1997; Lyver et al., 2008, 2009).

One current cause of contention is in the customary use and consumption of native birds, such as the kereru/kukupa. It could be implied within the Tūhoetanga rights given to Te Urewera in the 2014 Act is the ability for Tūhoe to consume kereru/kukupa if the populations are not threatened (Weaver, 1997; Lyver et al., 2008, 2009; Te Urewera Act, 2014). This mahinga kai is in direct contrast to both the New Zealand Wildlife Act 1953, and the intentions of the Department of Conservation (DOC), which strictly prohibit the hunting and consumption of many native species, including kereru/kukupa (Wildlife Act, 1953; Jones, 2015).

Close-up of a kereru/ kukupa, traditionally harvested by many iwi.

Judi Lapsley Miller, 2017.

Issues like this will need to be more regularly acknowledged to allow greater Maori input into co-management systems (Wildlife Act, 1953; Jones, 2015).

Regarding Te Urewera, some balance will be required. Crown and DOC conservationists will need to take a step back to fulfil the intentions of Tūhoetanga from the Te Urewera Act (Ruru, 2014; Te Urewera Act, 2014). The greater representation of Tūhoe members on the Te Urewera Board is an important address of this issue (Te Urewera Act, 2014). Going forward, we need to be aware of how we can continue to support this board as examples of co-management systems around the world have shown removal of power from western conservationists can result in conservation efforts receiving less money and resources (Nadasdy, 2005; Blaser, 2009;).

Acknowledging and mitigating these critique of co-management would allow Te Urewera to benefit from a wider knowledge base from which to carry out conservation and set an example for co-management worldwide (Ruru, 2014; Te Urewera Act, 2014; Dale & Petronelli, 2018).

Conclusion: A way forward

If this Tūhoe-led co-management scheme is successful it will be an excellent indicator for how we can adapt current methods of New Zealand conservation, which largely centre on the use of reserves (Nadasdy, 2005; Blaser, 2009; Saunders & Norton, 2001; Magallanes, 2015). Land rights afforded to Maori people with the Treaty of Waitangi were not honoured, disconnecting many from traditional values and practices tied to the land (Magallanes, 2015). This emphasises a need for reparations of Maori grievances and an opportunity to allow Maori values to be incorporated in the conservation sphere (Magallanes, 2015).

There is a potential for our reserves to be managed differently, in a way that still promotes conservation but allows a larger involvement from Maori, such as the intention of Te Urewera. An effective co-management system could allow a wider perspective and knowledge base from which to carry out more effective preservation and restoration. An initiative benefitting the environment for all New Zealanders set a precedent for the rest of the world to follow.

Glossary

Crown: Refers to the British Crown, sovereignty over the commonwealth including New Zealand

Iwi: Largest social grouping of Maori, commonly translated to tribe.

Kereru/Kukupa: New Zealand wood pigeon (Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae).

Mahinga kai: Customary use/ utilisation of lands natural resources in a sustainable fashion.

Maori: Indigenous peoples of New Zealand

Te Urewera: Area of land located on the eastern side of the North Island of New Zealand

Treaty of Waitangi: New Zealand founding document that aimed to establish relationship between Maori and the Crown and Maori land rights and subjectivity under the Crown.

Tūhoe: Iwi inhabiting the eastern areas of the North Island of New Zealand, covering Te Urewera

Tūhoetanga: Tūhoe culture and connection to the land (Te Urewera).

References

Arif, A. (2015). New Zealand’s Te Urewera act 2014. Native Title Newsletter, (Apr 2015), 14.

Blaser, M. (2009). The threat of the Yrmo: the political ontology of a sustainable hunting program. American Anthropologist, 111(1), 10-20.

Dale, G., & Petronelli, G. (2018, April). Legal personhood for nature has legal ramifications. Retrieved from https://www.laneneave.co.nz/legal-personhood/

Hill, C. J., & McKay, B. (2018). Binding Significance: Reflections on the Demolition of the Aniwaniwa Visitor Centre, Te Urewera. Fabrications, 28(2), 235-255.

Jones, N. (2015, July). Conservation Minister Maggie Barry rejects kereru eating. Retrieved from https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11484033

Lyver, P. O. B., Taputu, T. M., Kutia, S. T., & Tahi, B. (2008). Tūhoe Tuawhenua mātauranga of kererū (Hemiphaga novaseelandiae novaseelandiae) in Te Urewera. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 7-17.

Lyver, P., Jones, C., & Doherty, J. (2009). Flavor or forethought: Tuhoe traditional management strategies for the conservation of kereru (Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae novaeseelandiae) in New Zealand. Ecology and Society, 14(1).

Magallanes, C. J. I. (2015). Nature as an ancestor: two examples of legal personality for nature in New Zealand. VertigO-la revue électronique en sciences de l’environnement, (Hors-série 22).

Nadasdy, P. (2005). The anti-politics of TEK: the institutionalization of co-management discourse and practice. Anthropologica, 215-232.

Ruru, J. (2014). Tūhoe-Crown settlement–Te Urewera Act 2014. Māori Law Review, 22(October).

Saunders, A., & Norton, D. A. (2001). Ecological restoration at mainland islands in New Zealand. Biological Conservation, 99(1), 109-119.

Te Urewera Act 2014. [accessed 2019 May 10]. http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2014/0051/20.0/DLM6183601.html#DLM6183606

Weaver, S. (1997). The Call of the Kererū: The Question of Customary Use. The Contemporary Pacific, 383-398.

Wildlife Act 1953 [accessed 2019 May 15]. http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1953/0031/72.0/DLM276814.html#DLM277089