Collaboration and Integration, a Key Part of Innovation

Posted: June 5, 2019 Filed under: 2019, conservation, ecology, ERES525, Uncategorized Leave a comment Institute for science and human values. 2018

Institute for science and human values. 2018

By Alanna Smith

Abstract

Conservation management has transformed over the years from initially focusing on restoration practices to now evolving into reconciliation approaches. Unlike restoration practices that are species-focused, reconciliation conservation requires an integrated approach that incorporates human cultures, values as well as the role of science. Identifying key values held by people are necessary, as values guide what people attend to do. Not all groups however hold the same motivating values. As a result, the need to find co-values or common values is crucial for researchers or policymakers to then use as guidelines to shape management projects. The role of science is necessary to provide data and facts needed to assist community groups in making valuable decisions. With people now encroaching more into natures space, how we manage these spaces requires working more with people and understanding why they do what they do.

Integrated Conservation Management

Informed conservation decisions require the integration of both facts and values (Dietz 2013). Science is able to provide factual information to enable the public to make informed decisions based on real data (Manfredo et al 2016). The collected data combined with those motivating values held by people, groups and societies then inform conservation decision-making processes that can help shape a socially supported management project (Manfredo et al 2016). The inclusion of stakeholder values in conservation and restoration ecology is not only necessary to mitigating conflict, but also encourages public participation in policies (Redpath et al 2012). Such action is important as people’s values are what underpin specific preferences for one course of action over another (Dietz 2013). In an age of increasing anthropogenic impacts on natural systems, recognising how and why people value different aspects of ecological systems are now needed to promote the social acceptability of management activities (Ives & Kendal 2014)

A shift in conservation management thinking

Integrating science with social science demonstrates conservation management is moving towards a more collaborative and integrated management approach. Such a shift is needed in order to manage nature in a way that can maximize the overall value of the human condition (Mace 2014). For example, maximising benefits gained from ecosystem services such as the value of water used for irrigation, forests that store carbon and human welfare benefits from the aesthetic value nature provides (Fisher & Turner 2008). With conservation previously having a restoration focus on species conservation, has now been transformed into reconciliation approaches. The transformation now including the integration of cultural structures and institutions to develop sustainable and resilient interactions between human societies and the natural environment (Mace 2014).

People and nature

When recognising those values associated with researchers in science, they are often more interested in assigned values associated with project donors rather than underlying values (i.e. species, ecosystems or places) (Ives & Kendal 2014). Social science, however, in ecological management ensures that those underlying values are taken into account (Endter-Wada et al 1998). As a result, the opportunity to hear social, cultural, ethical and spiritual concerns are achieved (Dearden et al 2018). Values are a fundamental part of how people engage with conservation issues, i.e., by having a “natural connection between place and decision-making” (Brown and Reed 2012 p. 320). Such opportunities to collaborate encourages the exchange of information, skill sharing and direct and indirect contributions of community groups (Glaser et al 2010).

Social concerns around the ‘Predator Free 2050’ approach

Predator Free NZ. 2017

A case study from New Zealand identifies a high-profile policy which has undergone critique on multiple levels, particularly social concerns due to the potential use of genetic modifications as an eradication tool to rid New Zealand of mammalian predators by the year 2050 (Owens 2017). The use of genetic modifications (GM) on target pest species to spread infertility as opposed to the alternative use of poisons has been proposed. The concept however is subject to national controversy due to a lack of public transparency on the issue (Fisher 2017).

Added social pressures have also come from those views of New Zealand indigenous Maori groups who also opposed poison and GM use within wildlife (Dearden et al 2017). Maori have inherited core values that have voice concerns about interfering with the tapu (scaredness) of species (Roberts & Fairweather 2004). These values are moral obligations that apply to specific actions regardless of the consequences (Ford et al 2012). The role of such moral obligation has received less attention when it comes to understanding what people will tolerate and accept (Ford et al 2012). Further research on values that incorporates a wider perspective than just the science can inform innovative conservation strategies, to improve the human component of conservation management (Manfredo et al 2017).

Identifying a common ground

Advertising Publications. 2019

Obtaining values from multiple stakeholders not only improves transparency, but provides an opportunity to incorporate views from various groups (Gavin et al 2015). Encouraging attempts to identify multiple views and values however can generate conflict, which not only threatens effective conservation but also prevents economic development, social equality and resource sustainability (Woodroffe 2005). It is highly difficult to convert or change people’s values and beliefs (Manfredo et al 2017). Hence it is important that all goals, values and potential trade-offs are made clear between stakeholders before seeking solutions, in order to identify co-values or co-beliefs (McShane et al 2011). For instance, a common environmental value for all parties involved in ‘Predator Free 2050’ would be the conservation and protection of New Zealand’s native birds. Discussions then around what tools would be used to preserve these species would then have to be further elaborated on with the assistance of scientific evidence as to what technologies could be used to achieve the objectives of that common goal. The data and models made available from researchers’ findings are important to not only ensure decisions are aligned with co-values, but to also ensure the public can compare the associated risks and benefits (Dearden et al 2018).

Conclusion

Understanding and engaging with societal values is now a critical part of ecological management, particularly now that we are living in a world where more species are increasingly sharing space with humans. No longer can ecological science triumph on its own. The necessary changes we now need to sustainably manage and restore our environment require the efforts of reconciliation through conscious environmental decisions and actions carried out by people today. Recognising what community groups value, are necessary to identify what makes people do what they do. Identifying co-values and co-beliefs are what is required to encourage behavioral changes needed to achieve management objectives. The quality of how those co-values are managed then requires the support of scientific findings to provide the data and evidence needed to make informed public decisions. Strengthening this collaborative relationship between both science and social science marks a new era in the realm of conservation and how it can be effectively managed today.

Reference

Advertising Publications. 2019. Knowing when, and how, to compromise at work. Retrieved from https://www.seattletimes.com/explore/careers/knowing-when-and-how-to-compromise-at-work/. 5th June 2019.

Brown, G.C., Reed, P. 2012. Social landscape metrics: measures for understanding place values from public participation geographic information systems (PPGIS). Landscape Research, vol. 37, no. 1

Dearden, P.K., Gemmell, N.J., Mercier, O.R., Lester, P.J., Scott, M.J., Newcomb,

R.D., Buckley, T.R., Jacobs, J.M.E., Goldson, S.G & Penman, D.R. 2018. The potential for the use of gene drives for pest control in New Zealand: a perspective, Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 48:4, 225-244,

Dietz, T., Fitzgerald, A., Shwom, R., 2005. Environmental Values. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 30, 335–372.

Einhorn, H. J., & Hogarth, R. M. (1981). Behavioural decision theory: Processes of judgement and choice. Annual Review of Psychology, 32, 53-88.

Endter-Wada, J., Blahna, D., Krannich, R., Brunson, M. 1998. A Framework for Understanding Social Science Contribtions to Ecosystem Management. Ecological Society of America

Fisher, D. 2017. The big read: What happened when one expert killer was visited by the US military’s science agency. New Zealand Herald.

Fisher, B & Turner, R.K. 2008. Ecosystem services: Classification for valuation. Biol Con. Vol. 141. No. 5

Ford, R.M., Williams, K.J.H., Smith, E.L., Bishop, I.D., 2012. Beauty, Belief, and Trust: Toward a Model of Psychological Processes in Public Acceptance of Forest Management. Environ. Behav.

Gaven, M.C., McCarter, J., Mead, A., Berkes, F. 2015. Defining biocultural approaches to conservation. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. Vol. 30, no. 3

Glaser, A., van Klink, P., Elliott, G & Edge, K. 2010. Whio/blue duck (Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos) recovery plan 2009-2019. Publishing Team, Department of Conservation, New Zealand.

Institute for science and human values. 2018. I believe in science and human values and I vote. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/scienceandvalues/posts/reposting-because-today-is-the-day/1909331262435859/. 5th June 2019.

Ives, C and Kendal, D 2014, ‘The role of social values in the management of ecological systems’, Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 144, no. 1, pp. 67-72.

Mace, G.M. 2014. Whose conservation?

Manfredo M J., Bruskotter J T., Teel T L., Fulton D., Schwartz S H., Arlinghaus

R., Oishi S., Uskul A K., Redford K., Kitayama S., Sullivan L. 2016. Why social values cannot be changed for the sake of conservation. Conservation biology; 31:4

McShane, T.O., Hirsch, P.D., Trung, T.C., Songorwa, A.N., Kinzig, A., Monteferri, B., Mutekanga, D., Thang, H.V., Dammert, J.L., Pulgar-Vidal, M., Welch-Devine, M., Brosius, P., Coppolillo, P., O’Connor, S. 2011. Hard choices: Making trade offs between biodiversity conservation and human well-being. Biological Conservation. Vol 144: 3: 966-972

Owens B. 2017. Behind New Zealand’s wild plan to purge all pests. Nature. 541:148–150

Redpath, S.M., Young, J., Evely, A., Adams, W.M., Sutherland, W.J.,

Whitehouse, A., Amar, A., Lambert, R.A., Linnell, J.D.C., Watt, A., Gutierrez, R.J. 2013. Understanding and managing conservation conflicts. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. Vol. 28, No, 2.

Roberts M, Fairweather JR. 2004. South Island Māori perceptions of biotechnology. Research Report No. 268. Christchurch: Lincoln University.

Tim James. 2017. Predator Free NZ. Retrieved from https://www.birdlife.org/pacific/news/new-zealand-free-invasive-predators-2050. 5th June 2019.

Woodroffe, R. 2005. People and Wildlife: Conflict or Coexistence?, Cambridge University Press

The Role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Conservation.

Posted: June 5, 2019 Filed under: 2019, ERES525, Module Critique Assignment | Tags: Traditional ecological knowledge Leave a commentPenny Ixer

Abstract:

Traditional ecological knowledge may provide a fundamental tool for restoration and conservation management. Threatened by global social change, traditional ecological knowledge is the cumulative knowledge, beliefs, and practices related to ecosystems and formed over time by an indigenous group. Establishing the potential role traditional ecological knowledge can play in conserving ecosystems, this module suggests the acknowledgment and incorporation of traditional ecological knowledge with Western science will result in effective conservation management. A case study of the traditional ecological Maori hold for tuatara, demonstrated the ways knowledge is passed through generations and how values form over time. The Maori and tuatara case study added further evidence of how traditional ecological knowledge can inform conservation management when complemented by Western science. The loss of traditional ecological knowledge due to global social change, was found to be a key factor limiting the successful implementation of traditional ecological knowledge into conservation. Altering education curriculum to account for traditional ecological knowledge may provide a solution to countering the loss of traditional ecological knowledge, de-marginalizing indigenous communities as a result.

Introduction:

Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) is defined as the cumulative knowledge, practices, and beliefs that local and indigenous people hold for environments, biodiversity and ecosystems (Kimmerer, 2002; McCarter & Gavin, 2014b). TEK can provide a fundamental tool for restoration and conservation projects, utilizing collective ecological understanding to direct adaptive management (Berkes, Colding & Folke, 2000). Social change however is threatening the persistence of TEK, disrupting the cultural transmission and acquisition of knowledge and subsequently diminishing the role TEK may play in conservation (McCarter & Gavin, 2014a).

To begin, the module will further define TEK, how it is transmitted, and the role it can play in conservation. A case study demonstrating how Maori TEK has been utilized for the conservation management of tuatara will highlight the potential value TEK holds for conservation. The module will conclude by describing how education systems may create opportunities to maintain TEK in socio-cultural contexts.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge and its Role in Conservation:

The product of a lasting connection between indigenous people and their local ecosystems, TEK is formed through observations (McCarter & Gavin, 2014b; Kimmerer, 2002). Shared from generation to generation, TEK is continuously built upon. TEK may provide an invaluable tool for conservation, using localized, extensive knowledge to effectively conserve ecosystems (Drew, 2005). The sustainable agroforestry management by the Lacandon Maya in Mexico and Central America is based upon TEK, and is positively related to soil restoration (Falkowski et al., 2016; Diemont et al., 2011). The TEK of the Lacandon Maya could be utilized for the restoration of degraded forests in surrounding areas, and other similar forests (Falkowski et al., 2016; Diemont et al., 2011). Previously marginalized by Western science, TEK is increasingly being recognized for its conservation value around the world (Kimmerer, 2002; Uprety et al., 2012).

In combination with Western science, TEK can be utilized to support the restoration and management of ecological systems. In western Washington State, USA, the Nisqually Tribe incorporate Western ecological science with their TEK to restore the Nisqually river system, and its accompanying natural resources of biological and cultural value (Johnson et al., 2016). TEK adapts to changes in ecological systems over time, which may be used in conservation to promote adaptive and resilient ecosystems able to withstand dramatic environmental change, such as climate change (Mcmillen et al., 2017). Acknowledging the value of TEK in conservation, may enable indigenous communities and conservationists to more effectively conserve ecosystems. TEK loss, however, creates a significant hurdle to the implementation of TEK into conservation (Tang & Gavin, 2010).

Maori Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Tuatara (Sphenodon):

The case study of the Maori TEK of tuatara demonstrates how the values, knowledge and practices of indigenous groups contribute to the formation of TEK, and how TEK may inform conservation. Based on their locally developed observations and practices, indigenous groups often hold unique knowledge and values regarding ecological systems (Berkes et al., 2000). Maori possess crucial TEK of many endemic New Zealand species. A study by Ramsted et al., (2007) assessed Maori TEK of tuatara, conducting interviews with elders from Te Atiawa, Ngati Koata, and Ngati Wai Iwi (guardians of islands inhabited by tuatara).

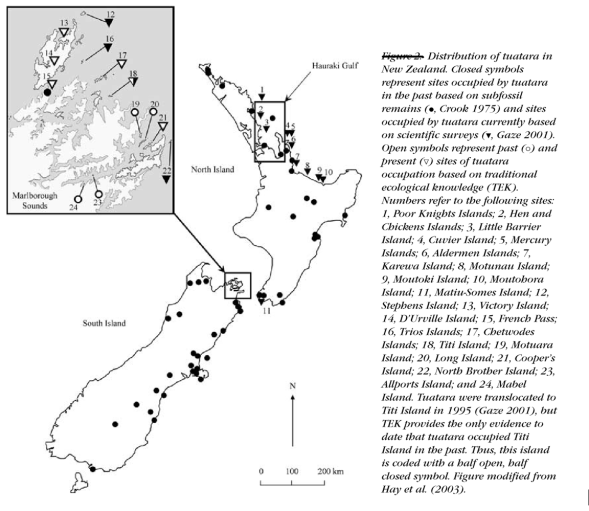

Valued by many Maori for its cultural significance, Maori TEK of tuatara may aid the conservation of the declining species. Personal observations and storytelling by Maori elders, has carried knowledge of the tuataras’ cultural significance through generations, creating a sense of respect, reverence and fear of tuatara (Ramsted et al., 2007). Maori TEK of the tuataras’ biology and ecology, while less detailed compared to TEK of tuataras’ cultural significance, still became a crucial tool in the conservation of tuatara. Maori TEK contributed to the conservation of tuatara in four ways: by providing evidence of seven sites previously occupied by tuatara (refer to Figure 1), suggesting five sites still possibly occupied by tuatara, proposing novel hypotheses for scientific testing, and finally by describing the previously unknown cultural role of tuatara (Ramsted et al., 2007). Combining Maori TEK with scientific ecological knowledge better informed the conservation of tuatara, perhaps leading to more effective species management. As Maori iwis’ each possess considerable TEK, a partnership of knowledge between Maori and Western science should be considered for the conservation of many New Zealand species. Numerous other socio-cultural contexts should also attempt to integrate TEK into conservation and restoration ecology.

Figure 1: Demonstrating the distribution of tuatara in New Zealand. Closed circles represent sites occupied by tuatara based on fossil records and scientific surveys. Open symbols represent past and present tuatara sites based on Maori TEK. Photo Credit: Ramsted et al., (2007).

Education to Prevent Loss of Traditional Ecological Knowledge:

TEK may provide an invaluable tool for restoration and conservation, however worldwide social change is continuously contributing to TEK loss. Current education systems in many places around the world fail to adequately incorporate TEK into their curriculum, diminishing the value of indigenous TEK. A study conducted by McCarter and Gavin, (2014b) interviewed three communities on Malekula Island, Vanuatu, discovering the common perception of TEK loss. TEK is a fundamental element of life in Vanuatu, hence the concern for TEK loss is founding the diversification of education systems. Kastom (traditional culture) schools on Malekula Island may provide numerous opportunities to maintain TEK (refer to Figure 2) (McCarter & Gavin, 2014a). Kastom schools, however, are challenged by a lack of funding and the changed form of cultural transmission (from traditional storytelling by elders). Integrating indigenous TEK into mainstream education will allow for inter-generational transmissions of knowledge, and will potentially give indigenous TEK the same status as Western scientific knowledge and values (McCarter & Gavin, 2011; Chandra, 2014). Legitimizing TEK through education systems may also increase younger generations’ involvement with conservation.

Figure 2: Traditional ecological knowledge is part of everyday life in Vanuatu. Kastom schools in may allow the cultural transmission of traditional ecological knowledge. Kastom refers to traditional culture, including beliefs, practices and values. Photo Credit: Unicef.

Conclusion:

Providing a wealth of knowledge TEK may provide an invaluable tool for conservation. Incorporating Maori TEK into the conservation of tuatara, ultimately enabled a greater understanding of tuataras’ cultural significance, biology and ecology. The implementation of TEK into conservation could be attempted by many socio-cultural contexts, allowing indigenous knowledge and values to play a key role in conservation. Global social change causing the loss of TEK can be potentially mitigated by changing education curriculum. Education systems incorporating TEK will allow the cultural transmission of knowledge, potentially legitimizing TEK to the same status as Western science, and de-marginalizing indigenous communities such as Maori.

References:

Berkes, F., Colding, J., Folke, C. (2000). Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecological Applications, 10(5), 1251-1262.

Chandra, D. V. (2014). Re-examining the importance of indigenous perspectives in the western environmental education for sustainability: “From tribal to mainstream education”. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 16(1), 117-127.

Diemont, S. A. W., Bohn, J. L., Rayome, D. D., Kelsen, S. J., & Cheng, K. (2011). Comparisons of Mayan forest management, restoration, and conservation. Forest Ecology and Management, 261(10), 1696-1705.

Drew, J. A. (2005). Use of traditional ecological knowledge in Marine Conservation. Conservation Biology, 19(4), 1286-1293.

Falkowski, T. B., Diemont, S. A. W., Chankin, A., & Douterlungne, D. (2016). Lancandon Maya traditional ecological knowledge and rainforest restoration: Soil fertility beneath six agroforestry system trees. Ecological Engineering, 92, 210-217.

Johnson, J. T., Richard, H., Cajete, G., Berkes, F., Louis, R. P et al. (2016). Weaving indigenous and sustainability sciences to diversify our methods. Sustainability Science, 11(1), 1-11.

Kimmerer, R. W. (2002). Weaving traditional ecological knowledge into biological education: A call for action. Bioscience, 52(5), 432-438.

McCarter, J., & Gavin, M. C. (2011). Perceptions of the value of traditional ecological knowledge to formal school curricula: opportunities and challenges from Malekula Island, Vanuatu. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 7, 38.

McCarter, J., & Gavin, M. C. (2014a). In situ maintenance of traditional ecological knowledge on Malekula Island, Vanuatu. Society & Natural Resources, 11, 1115-1129.

McCarter, J., & Gavin, M. C. (2014b). Local perceptions of changes in traditional ecological knowledge: A case study from Malekula Island, Vanuatu. AMBIO, 43(3), 288-296.

Mcmillen, H., Ticktin, T., Springer, T., & Kihalani, H. (2017). The future is behind us: Traditional ecological knowledge and resilience over time on Hawai’i Island. Regional Environmental Change, 17(2), 579-592.

Ramstad, K. M., Nelson, N. J., Paine, G., Beech, D., Paul, A., Paul, P., Allendorf, F. W., & Daugherty, C. H. (2007). Species and cultural conservation in New Zealand: Maori traditional ecological knowledge of tuatara. Conservation Biology, 21(2), 455-464.

Tang, R., & Gavin, M. C. (2010). Traditional ecological knowledge informing resource management: Saxoul conservation in inner Mongolia, China. Society & Natural Resources, 23(3).

Uprety, Y., Asselin, H., Bergeron, Y., Doyon, F., Boucher, J-F. (2012). Review article: Contribution of traditional knowledge to ecological restoration: Practices and application 1. Ecoscience, 19(3), 225-237.

Contribution of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in restoration ecology and sustainable resource use: Based on a case study of Titi bird Harvesting

Posted: June 5, 2019 Filed under: 2019, ERES525 | Tags: Rakiura Maori, sustainable harvesting, Titi bird, Traditional ecological knowledge Leave a commentBy Liduli Livera

Abstract:

Social and cultural constructs tend to shape human needs and interactions with the nature. And sometimes these overrule the scientific facts when come to decision making. Likewise Traditional Ecological Knowledge plays an important role in Rakiura Maori for sustainable Titi bird harvesting practices. It comprise of ecology and behaviour of titi birds. Knowledge on harvesting and processing of the birds are passed down from generation to another through word of mouth and practice. With the declining numbers of Titi birds in the islands, scientists are more concerned about the conservation of Titi bird populations. Since the harvesting traditional practice is considered as a part of Rakiura Maori culture, they also highly value the sustainable harvesting practices to ensure continuation of the populations for their future generations. Therefore as the best solution, traditional knowledge is included in island management plans. The practice has proven to be successful in Titi bird population management and it shows the importance of use of adaptive co-management for conservation of natural resources which are attached with valuable social values and traditions.

Introduction:

People and nature cannot be considered as separate parts in environment as they are linked and interdependent on each other in many ways.1 In most wilderness areas local people are connected with their nature through traditional and cultural relationships. Mostly conservationist explain the potential impacts of a loss of a threatened species but they usually tend to forget to explain the impact of that loss to the human cultures or values which had traditional connections with that specific species.2 Combining the available new knowledge with the traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) can be the best cost-effective and participatory solution to this issue as it addresses many stakeholder interests.3 A significant gap in restoration ecology and conservation can be filled by facilitating new pathways by bridging TEK and modern science.

TEK is all about application of accumulated traditional knowledge, values and beliefs passed from one generation to other.4,5,6 It has become an important component in conservation in recent years with the understanding of contribution for rare, threatened and ecologically important species and ecosystems conservation and restoration.7 TEK is used for prediction of environmental events and these outcomes are usually obtained through extensive observation of a species or an ecosystem. Also it allows humans to live in harmony with nature while utilizing the natural resources in sustainable manner.5,8 It can become very useful in in-situ conservation and restoration projects as the traditional knowledge is based on the sustainable utilization of a particular land or a natural resources which they dwell and rely on throughout their lives.5,9 Although it is commonly believed that TEK is not a suitable knowledge system to adapt into sustainable harvesting practices as the old knowledge lacks ability to adapt into recent global environmental changes,10,11 it often provides examples of cultures which keep the balance between nature and guide sustainable use of natural resources.12

Maori traditional knowledge in New Zealand is one of the knowledge systems which have more concern on the conservation of resources for human utilization.9 Contribution of the Maori TEK in conservation and restoration of a species is further described in this article using a case study of customary Titi bird harvesting.

Sustainable Titi bird harvesting

It is a tradition and a cultural identity of Rakiura Maori to harvest chicks of Titi bird (Puffinus griseus) also called as sooty shearwaters or muttonbirds. The harvesting is done in islands in Foveaux Strait and adjacent to Stewart islands in New Zealand (Figure 1). The harvesting period continues for 2 months and during this period Rakiura Maori are allowed to harvest unlimited number of chicks according to their tradition.12,13 The first half of the harvesting season is called as ‘nanao’ and second is called as ‘rama’. In ‘nanao’ chicks are extracted out from the breeding burrows in the daytime and in ‘rama’ chicks are caught out in the breeding ground at night when they come out from the burrows.12,13,14 Knowledge about harvesting seasons, locations of birding grounds, techniques of hunting chicks and processing the meat is passed down through generations.12

Figure 1: A map of the islands where the traditional Titi bird harvesting is conducted. (Source: Lyver, 2002)

Titi birds are facing a massive decline in their populations due to several reasons. Climate change, introduced mammalian predators, fisheries by-catch and traditional harvesting practices are the top threats to the species.15,16,17

Figure 2: Photograph of a Titi bird chick (Source: Stuff.co.nz)

In order to identify the best practice and contribution of TEK of Rakiura Maori for Titi bird conservation, a study was conducted by a research group of University of Otago. According to the study, the main concern of the Maori is to keep the birds for the future generations, so the Titi bird harvesting tradition could be continued forever. And the main concern of conservationists is to conserve the species and to control the declining populations. Achieving both these purposes a legislation was implemented to control the sustainable resource utilization by habitat protection and adult bird conservation while minimizing conflicts in both parties.18 The important values and traditions of the Rakiura Maori are therefore included in legislations to conserve the Titi birds in New Zealand.19 This represents adaptive co-management practices by inclusion of science along with the traditional knowledge for island management plans.20

Figure 3: An old picture of the customary Titi bird harvesting in New Zealand. The birders in the picture are carrying hand-made kelp bags filled with the harvested chicks. (Source: New Zealand Geographic)

Titi harvesting control is under the Rakiura Maori people who manage it without imposing any formal limits to the maximum number of individuals to be harvested during a season. The management relies on social institutions to ensure sustainability of harvesting. A supervisor is being appointed since the first legislation was set out for Titi bird harvesting. (Land Act Regulation, 1912) The supervisor is elected from the elderly people in the tribe and he is given the authority to decide on the start and ending of the harvesting periods, locations and restrictions for harvesting, restoration of breeding grounds etc. Also disputes arisen among the community are solved by the supervisor and if not they are reported to the Department of Conservation.13

Rakiura Maori follows several strategies and practices to ensure the sustainability of their tradition. According to the tradition the people prevented disturbance to breeding grounds during the mating seasons of the birds. Access is only given to certain individuals in the community and that is also with a temporal restriction to the harvesting season.18 in the islands, the fragile and sensitive habitat patches are considered as sacred and access is banned for the hunters. Cutting of live trees for gathering as firewood is also prohibited and trees which are used by Titi birds as taking-off for flying are nurtured with care. During harvesting seasons, the harvesting is done with minimal damage to the breeding grounds and burrows. The burrows which are disturbed largely due to digging are restored back and the burrow entrances are cleared of any barriers to provide readily accessible breeding grounds to adult birds. To have an impact on the declining populations, harvesting of adult bids are prohibited and to avoid harvesting of chicks in non-target life stages, specific techniques are adopted by hunters. Also special techniques are used in effective processing of harvested chicks to minimize the wastage.13 These practices have largely helped to control the over exploitation of the Titi birds while maximizing the harvest.

Conclusion

It is important to understand the customary laws and traditions of indigenous people and their adaptation to changing environmental conditions. Also it allows active management of threats imposed to the natural resources and their social norms by the climate change, over utilization of resources with population growth, economic systems and social pressure on traditional practices.13 Social mechanisms can be more effective and cost-effective than the formal legislations as they are emerging through the community itself. The challenge is to combine science and TEK into one practice while taking the strengths and weaknesses into consideration. Rakiura Maori and New Zealand government has successfully addressed this issue by adapting co-management practices for island Titi bird population management. Rakiura Maori have a spiritual and emotional connection to these islands therefore the continuation of the tradition is very important to them.13 Respecting different knowledge systems is very important to construct a participatory solution to the number of fast declining valuable species all over the world.

One of the challenges and barriers that Maori will have to face in the future is the change in modern life styles in younger generation. The valuable traditional knowledge is not properly transmitted to the next generation and the practices are not properly continued in harvesting seasons due to busy time schedules of the young.13 Sustainable harvesting practices and restoration of habitats will be lost when passing through generations. Also it is important to conduct research and study further the traditional knowledge of harvesting techniques and to keep records for future reference.

This adaptive co-management is proven to be a good example for management of natural resources with strong attachment to their local communities. The values of small scale societies living close to critical biodiversity locations can become very important for conservation concerns.1

References

- Manfredo, M.J., Bruskotter, J.T., Teel, T.L., Fulton, D., Schwartz, S.H., Arlinghaus, R., Oishi, S., Uskul, A.K., Redford, K., Kitayama, S. & Sullivan. L. (2016). Why Social Values Cannot Be Changed for The Sake of Conservation. Conservation Biology, 31(4). Pg,. 772-780.

- Salmon, E. (2000). Kinentric Ecology: Indigenous Perceptions of the Human-nature Relationship. Ecological Applications. 10(5). Pg. 1327-1332.

- Warren, D.M., Slikkerveer, J. & Brokensha, D. (1991). Indigenous Knowledge Systems: The Cultural Dimensions of Development. Kegan Paul International, London.

- Turner, N.J., Ignace, M.B. & Ignace, R. (2000). Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Wisdom of Aboriginal Peoples in British Colombia. Ecological Applications. 10(5). Pg. 1275-1287.

- Agrawal, A. (1995). Dismantling the Divide between Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge. Development and Change. Backwell Publishers, UK. 26. Pg. 413-439.

- Berkes, F. (1999). Sacred Ecology: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resource Management. Taylor and Francis, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

- Berkes, F., Colding, J. & Folke, C. (2000). Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as Adaptive Management. Ecological Applications. 10(5). Pg. 1251-1262.

- Anderson, D. & Grove, R. (1987). Conservation n Africa: People, Policies and Practice. Cambridge University Press, UK.

- Moller, H. (1996). Customary Use of Indigenous Wildlife- towards a Bi-cultural Approach to Conserving New Zealand’s Biodiversity. Biodiversity: Papers from a seminar series on a biodiversity science and research division. Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand.

- New Zealand Conservatio Authority (NZCA) (1997). Maori Customary Use of Native Birds, Plants and Other traditional Materials. New Zealand Conservation Authority, Wellington, New Zealand.

- Newman, J. & Moller, H. (2005). Use of Matauranga (Maori Traditional Knowledge) And Science To Guide A Seabird Harvest: Getting the Best of Both Worlds? Indigenous Use and Management of Marine Resources. Senri Ethnological Studies, 67. Pg. 303-321.

- Lyver, P.O. (2002). Use of Traditional Knowledge by Rakiura Maori to Guide Sooty Shearwater Harvests. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 30(1). Pg. 29-40.

- Moller, H., Kitson, J.C. & Downs, T.M. (2009). Knowing by Doing: Learning for Sustainable Muttonbird Harvesting. New Zealand Journal of Zoology, 36(3). Pg. 243-258.

- Stevens, M.J. (2006). Kai Tahu me te hopu tiki ki Rakiura: An Exception to the Colonial Rule?. Journal of Pacific History. 41(3). Pg.273-291.

- Newman, J., Clucas, R., Moller, H., Fletcher, D., Bragg, C., Mckechnie, S. & Scott, D. (2008). Sustainability of Titi Harvesting by Rakiura Maori: A Synthesis Report. University of Otago Wildlife Report, 210.

- Lyver, P.O., Moller. H. & Thompson, C. (1999). Changes in Sooty Shearwater Puffinus griseus Chick Production and Harvest Presede ENSO Events. Marine Ecology Progress Series 188. Pg. 237-248.

- Uhlmann, S.S., Fletcher, D. & Moller, H. (2005). Estimating Incidental Takes of Shearwaters in Driftnet Fisheries: Lessons for The Conservation of Seabirds. Biological Conservation. 123. Pg. 151-163.

- Kitson, J.K. & Moller, H. (2008). Looking After Young Ground: Resource Management Practice by Rakiura Maori Titi Harvesters. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania. 142. Pg. 161-176.

- Department of Lands and Surveys (1978). The Titi (Muttonbird) Islands Regulations 1978/59. Land Act Regulations 1949, Wellington, New Zealand.

- Moller, H., Lyver, P.O., Bragg, C., Newman, J., Clucas, R., Fletcher, D., Kitson, J., McKechnie, S. & Scott, D. (2009). Guidelines for Cross-cultural Participatory Action Research Partnerships: A Case Study of A Customary Sea Bird Harvest in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 36. Pg. 211-241

The Cultural Health Index: Bringing together Traditional Knowledge and Western Science

Posted: June 4, 2019 Filed under: 2019, ERES525, Module Critique Assignment, Uncategorized | Tags: #restoration, conservation, culture, freshwater, rivers, streams, traditional, Values Leave a commentBy Liam McAuliffe

Section of the Taieri River, one of the first freshwater systems to be officially analysed by the Cultural Health Index.

-Phillip Capper, 2007.

Abstract

A significant number of New Zealand freshwater systems are degraded by excess sedimentation and nutrients as a result of urbanisation and agriculture. This degradation contributes to a decline in species and a disruption of freshwater communities. Additionally, Maori who traditionally value the ancestral life force of waterways find this degradation to damage their wellbeing and health.

This essay explores the use of the Cultural Health Index (CHI) in incorporating Maori values into the conservation of freshwater systems. I explore how this system, which is based upon five core traditional Maori values, has the capacity to assist conservation in three main ways. These are the identification of issues effecting waterways, the prioritisation of restoration projects, and the understanding and incorporation of Maori cultural issues in conservation planning.

Through this, councils gain new perspectives to contribute to conservation planning, and additional methodology to aid in the restoration of species and communities in our freshwater systems.

Introduction

Many New Zealand waterways are identified as having an excess of sedimentation and nutrients, such as nitrogen, which have damaging effects on the health of the water bodies and the species and communities that exist within them (Environment Aotearoa summary, 2019). Maori, who traditionally value waterways with mauri (life force) find the degradation of freshwater systems to be damaging to the health and wellbeing of local hapu (sub-tribes) (Morgan, 2006). For this reason there is a need for greater incorporation of traditional Maori values in conservation in New Zealand.

The Cultural Health Index (CHI) is an address of this issue. Created as a collaborative approach to restoration of freshwater systems, this practice incorporates both Maori traditional values and western scientific methods to create a system that effectively analyses freshwater health (Harmsworth et al., 2006).

This essay will explore the values that inform the CHI and how this method has been implemented into conservation. This shows how the CHI not only allows greater incorporation of Maori in conservation, but creates a new tool for diagnosing issues in freshwater systems which allows more effective prioritisation of species and community conservation (Tipa & Teirney, 2006a, Tipa & Teirney, 2006b).

How the Cultural Health Index works

The CHI is informed by five core Maori values in regards to freshwater systems. These are mauri, mahinga kai (utilisation of natural resources), kaitiakitanga (environmental guardianship), ki uta ki tai (holistic mountains-to-sea), and wai taonga (treasured waters) (Townsend et al., 2004).

Using these values, the CHI is then broken down into three main components. The first identifies freshwater systems that are of significance to Maori and hapu. The second explores the mahinga kai status of the waterbody, including its legal status and the ability for the water to be accessed. The third component functions similarly to western science methodology in its assessment of water health, incorporating details such as catchments and riparian buffers (Townsend et al., 2004; Harmsworth et al., 2006; Tipa & Teirney, 2006a).

The CHI was created as an easily accessible way for Maori to analyse freshwater health anywhere in New Zealand, regardless of location or type of water body (Tipa & Teirney, 2006). Its collaborative approach to traditional values and western science methods is unique and has the potential to inform more effective conservation throughout New Zealand.

Use of the Cultural Health Index

The CHI has been shown to be an effective way to analyse waterbody health if monitoring is regular and consistent (Tipa & Teirney, 2006b). It is effective in three main ways; identification of sites and issues, its role in restoration of species and communities, and its role in understanding Maori values.

Identification

The CHI allows identification of sites that are significant to Maori, whether the sites are unhealthy and the issues responsible for the degradation of these sites (Townsend et al., 2004; Harmsworth et al., 2006; Tipa & Teirney, 2006a, Tipa & Teirney, 2006b). The CHI takes into account areas surrounding the water body and quantifies urbanisation and agriculture, which have been shown to have damaging effects on the quality of waterways through increased sediment and nutrient levels (Tipa & Teirney, 2006b; Environment Aotearoa summary, 2019). Additionally, the CHI is able to identify changes in levels of fish and birds in the area, which is an indicator of freshwater health and feeds back into the Maori value of mahinga kai (Tipa & Teirney, 2006a, Tipa & Teirney, 2006b). Monitoring waterways regularly with CHI allows early identification of issues and an ability to observe changes within waterways.

Restoration

Identification of issues contributes to a more effective restoration of species and communities within freshwater systems. Side by side comparisons of the CHI and western methods show significant similarities in results, both being accurate surveys of stream health (Townsend et al., 2004; Harmsworth et al., 2006; Tipa & Teirney, 2006a, Tipa & Teirney, 2006b). Through this long-term approach to identification of issues and changes within freshwater systems, a more efficient prioritisation of restoration plans is possible (Tipa & Teirney, 2006a, Tipa & Teirney, 2006b). Having an organised prioritisation approach allows more effective restoration of species and communities which are most vulnerable to unhealthy waterways (Environment Aotearoa summary, 2019). This in turn allows exploration of possible freshwater management options and can influence regional council methods and plans (Tipa & Teirney, 2006a, Tipa & Teirney, 2006b).

Understanding

In addition to assisting in identification of issues and restoration of freshwater systems, the CHI has the capacity to increase Maori/council relations and build understanding of Maori cultural values and sites (Tipa & Teirney, 2006a, Tipa & Teirney, 2006b). This provides councils with a better understanding of the current issues surrounding freshwater systems from a Maori perspective, and some of the key issues regarding Maori connection to the water (Morgan, 2006; Tipa & Teirney, 2006a, Tipa & Teirney, 2006b). This in turn increases the incorporation of Maori in conservation by allowing Maori a larger input into determining policies of councils and making of plans (Townsend et al., 2004; Harmsworth et al., 2006; Tipa & Teirney, 2006a, Tipa & Teirney, 2006b).

Conclusion

Through the use of Maori traditional values to analyse the health of freshwater systems, the CHI has the capacity to aid in the identification of issues effecting waterways, to assist in the prioritisation of restoration projects, and to build an understanding and incorporation of Maori cultural issues in conservation planning.

Many New Zealand waterways have an excess of nutrients and sediments which are damaging freshwater species and communities (Environment Aotearoa summary, 2019). Maori, who are culturally impacted by this degradation, need to be more incorporated into the restoration of these damaged waterways. Through this incorporation of new perspectives and methods in freshwater conservation, we will benefit from a more effective and efficient restoration of species and communities.

References

Environment Aotearoa summary. (2019, April). Retrieved from https://www.mfe.govt.nz/Environment-Aotearoa-2019-Summary

Harmsworth, G. R., Young, R. G., Walker, D., Clapcott, J. E., & James, T. (2011). Linkages between cultural and scientific indicators of river and stream health. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 45(3), 423-436.

Morgan, T. K. K. B. (2006). Waiora and cultural identity: Water quality assessment using the Mauri Model. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 3(1), 42-67.

Tipa, G., & Teirney, L. D. (2006a). A cultural health index for streams and waterways: a tool for nationwide use (pp. 1-58). Wellington: Ministry for the Environment.

Tipa, G., & Teirney, L. D. (2006b). Using the Cultural Health Index: How to assess the health of streams and waterways. Ministry for the Environment, Manatū Mō Te Taiao.

Townsend, C. R., Tipa, G., Teirney, L. D., & Niyogi, D. K. (2004). Development of a tool to facilitate participation of Maori in the management of stream and river health. EcoHealth, 1(2), 184-195.